Vitamin, virility drug could treat preeclampsia

Treating disease doesn't always mean creating new drugs. Sometimes the therapies are already in our pharmacies and medicine cabinets.

Two labs in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology recently provided evidence for two new preeclampsia treatments that may be familiar: one a common dietary supplement, the other a little blue pill.

In separate tests, vitamin D and sildenafil (sold commercially as Viagra) were able to lower blood pressure in animal models of preeclampsia without compromising fetal health.

“In preeclampsia, there are two patients: mom and baby,” said Dr. Babbette LaMarca, associate professor of pharmacology. “You can't treat with heavy drugs and there's fear that if you reduce blood pressure too much, you may harm the baby.”

Preeclampsia occurs in 5-10 percent of pregnancies worldwide. Pregnant women will develop hypertension, reduced kidney function and placental ischemia - reduced blood flow to the baby.

The potential for birth defects with numerous anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive drugs limits management options. The only reliable treatment is delivery, but pre-term babies have a higher risk of health and developmental problems.

However, vitamin D is a strong anti-inflammatory hormone and deficiency of the vitamin is a preeclampsia risk factor, LaMarca said. So taking a supplement during pregnancy may be especially important.

The cause of preeclampsia isn't well understood, but it involves the immune system, said Dr. Jessica Faulkner, a postdoctoral researcher at Augusta University who recently completed her PhD in LaMarca's lab.

“In preeclampsia, we see an altered immune response,” Faulkner said. “The body may see the fetus as foreign and activate the immune system, especially the pro-inflammatory arm.”

Dr. Babbette LaMarca, associate professor of pharmacology, says that vitamin D supplements may improve blood pressure and inflammation in preeclampsia patients.

LaMarca, Faulkner and their colleagues studied how vitamin D counteracts inflammatory factors that lead to high blood pressure in preeclampsia. They used reduced uterine perfusion pressure rats, which undergo a procedure to give them similar symptoms to human preeclampsia. They then received vitamin D2 or D3 supplements or none as a control.

The researchers found that both vitamin D types lowered blood pressure, but LaMarca and her team wanted to know if the suspected factors leading to hypertension were also lowered.

The working hypothesis is a chain reaction: vitamin D decreases CD4+T counts, the cells involved in the body's immune response. This decreases AT1-AA, an autoantibody found in preeclampsia patients, leading to a decrease in proteins associated with hypertension and placental ischemia.

LaMarca and her team are the first to demonstrate that all of these factors associated with preeclampsia were reduced after vitamin D treatment. Vitamin D also lowered pup death rates, suggesting that the offspring benefit as well.

Meanwhile, another UMMC pharmacology lab is looking into the existing pharmacopeia to manage preeclampsia.

It may seem counterintuitive that a drug prescribed to men for erectile dysfunction could be beneficial for expectant mothers, but it makes perfect sense to researchers.

Sildenafil was first developed as an anti-hypertensive medication, but the side effects observed in some men were what made it a blockbuster drug, said Dr. Jennifer Sasser, assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology.

“Sildenafil opens blood vessels and increases blood flow by stopping the enzyme phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5), and we see that same enzyme in many blood vessels, in penile and uterine vasculature,” Sasser said. “It's a similar phenomenon, so sildenafil can counteract both high blood pressure and placental ischemia.”

Dr. Jenny Sasser, assistant professor of pharmacology, is testing sildenafil (sold commercially as Viagra) as a treatment for preeclampsia.

Sasser and her team treated rats with sildenafil during mid-pregnancy. They found decreases in blood pressure almost immediately after treatment, as well as improved kidney function, another indicator of preeclampsia.

There was also evidence that sildenafil lowered endothelin-1, one of the proteins that was also reduced by vitamin D treatment. Less endothelin-1 means less constriction in blood vessels, which treats both patients in the preeclampsia equation: the mother's blood pressure goes down, and the baby has a healthier placenta.

Sasser found that pups from sildenafil-treated rats were also longer and heavier than the controls. They also had lower placenta-to-pup weight ratios, which means that the placenta is working more efficiently.

Sasser's lab uses a different preeclampsia model, the Dahl salt-sensitive rat.

“They spontaneously develop hypertension and preeclampsia,” Sasser said, “and hypertensive women are at higher risk for developing preeclampsia,” so this model translates better to some human cases.

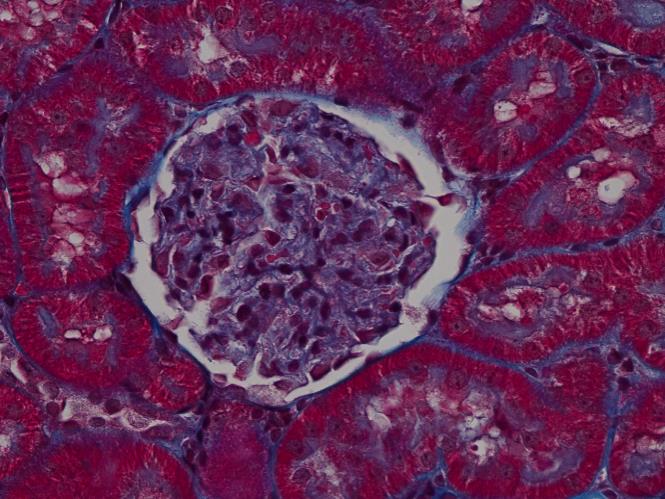

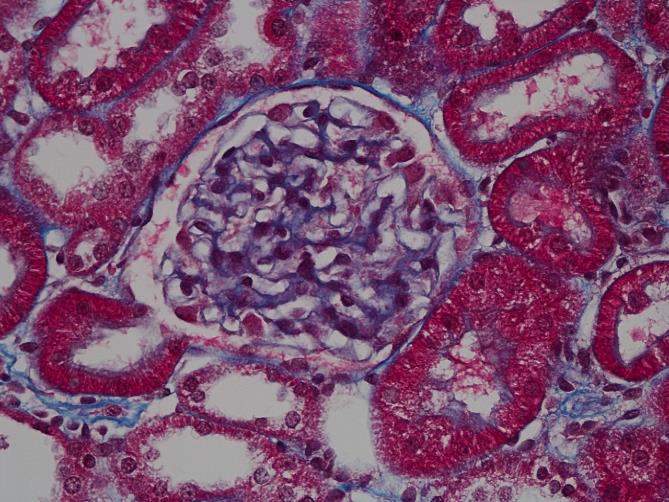

An enlarged glomerulus (center, a part of the kidney) in a Dahl SS rat not treated with sildenafil. Increased area and diameter are indicators of kidney damage associated with preeclampsia.

Glomerulus in Dahl SS rat after sildenafil treatment. The smaller size compared to the control indicates improved kidney function.

Sildenafil is already prescribed to some women to treat pulmonary hypertension, and a number of them have continued treatment throughout pregnancy, Sasser said, which speaks to its safety and potential for preeclampsia.

However, neither Sasser nor LaMarca can say for sure yet that their treatments are an effective therapy in women, due to a lack of large cohort studies.

So, has a cure for preeclampsia been hiding in our medicine cabinets? It's hard to say.

“People don't always look for simple answers, but then again, the answer may not be that simple,” LaMarca said.

One sure thing: the more treatments that can be tested, the better chances of finding ones that work.

The LaMarca paper will appear in an upcoming issue of the American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. The Sasser paper will appear in the March issue of the American Heart Association's journal Hypertension.