Averting HIV infection can depend on how well MSMs PrEP

When Jackson-area men who have sex with men get a prescription for a medication that can prevent HIV infection, which are more likely to take it as directed, or to come back to the prescriber for follow-up visits?

Just how much are their choices swayed by some unfortunate truths: that many at highest risk for the HIV infection have the least access to the drug, and that social determinants and behavioral norms work against them in seeking care in the first place?

A study of safety-net and specialty clinics in Jackson, St. Louis, Missouri, and Providence, Rhode Island sought to answer those questions by following about 300 men who have sex with men, or MSM, 86 of them in Jackson. The goal: Discover what’s really happening, not just what statistics might indicate, on how many MSM are taking PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, stay on their medication, and continue getting the care they need through follow-up clinic visits.

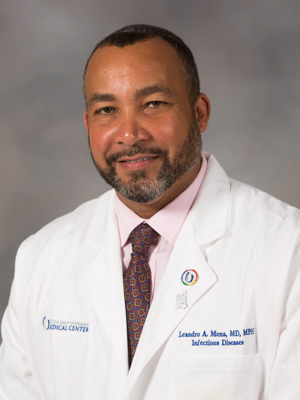

It’s the latest nationally heralded HIV research led by a group that includes Dr. Leandro Mena, University of Mississippi Medical Center professor and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences in the John D. Bower School of Population Health. Also a professor of medicine in infectious diseases, Mena directs the UMMC Center for HIV/AIDS Research, Education and Policy.

Results of the study, which examined data on one-year retention rates on PrEP use, were released last month at an international HIV prevention research conference in Madrid, Spain.

Researchers examined how many study subjects in the three cities followed through on a clinic visit three months later, versus how many of them fell into the “real world” category of missing that mark, but perhaps still taking their medications and making a return visit later that would qualify them as being persistent in PrEP care.

The Jackson clinic providing study data was Open Arms Healthcare Center, a community based clinic providing primary care and mental health services, including free HIV and STD testing and HIV prevention and treatment services. Its medical director is Dr. Laura Beauchamps, assistant professor of medicine in infectious diseases. Mena is a co-founder and former medical director.

In the overall study, “we’ve learned that although PrEP is probably the most effective method that we have in our toolkit to prevent HIV infection in people who are HIV negative, the real uptake of PrEP has been slow – and is slower in our region, especially among the population at highest risk,” Mena said.

Mena helped create Express Personal Health, a UMMC-operated clinic at the Jackson Medical Mall that fills a gap by providing access to free HIV testing and other sexual health screenings. Those testing negative for HIV, if at risk, are linked to comprehensive prevention services, including those that prescribe or provide the PrEP drug emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, known better by its trade name Truvada. It's a pill that people who don't have HIV, but whose sexual habits put them at risk, take daily to significantly reduce their chance of infection.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 1.1 million Americas can benefit from PrEP. While African Americans represent 44 percent of those who would benefit, only about 1 percent have been prescribed the drug. Latinos represent about 25 percent of those who would benefit, but only 3 percent are prescribed the drug.

The percentage for Mississippi men in the study coming back for care within the first eight months of a clinic visit was the lowest of the three cities represented – just 69 percent.

“Even for those who do start on PrEP, we know that they continue to experience significant challenges to continuing on it. Those challenges disproportionately affect younger individuals, and in Mississippi, younger men of color,” Mena said.

“The most important thing with PrEP is that they need to have lab work every three months to make sure they are still HIV negative, and STD testing and treatment also should be done every three months.”

Some of the reasons patients at risk of HIV don’t make clinic visits are among the reasons Mississippi has bad health outcomes. “We have the highest rate of uninsured individuals, poverty, lower educational attainment and poor health infrastructure, and a large number of the people we serve are below the poverty line,” Mena said.

“We know that in the real world, if they will come to the clinic and get their medicine, then they are likely to take it,” he said. “The challenge is implementing evidence-based findings into the real-world setting.”

Mena and Dr. Ben Brock, UMMC assistant professor of medicine in infectious diseases, are collaborating with Emory University, the National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in early 2019 on a clinical trial that explores whether a tailored approach to care for MSM ages 18-24 in rural areas and small towns will result in more of them taking the PrEP antiviral and getting regular care.

The “tailoring” comes through a smartphone app that allows patients to receive and manage their PrEP prescription and see Mena and Brock via telehealth without having to leave home. About 240 men, all HIV negative, from Mississippi, Georgia and North Carolina will be taking part in the study.

Participants will receive an “ePrEP” home care system that allows private, secure telemedicine visits. It will include a system to track PrEP shipments to the person’s home and materials to collect body fluid specimens to send to a laboratory for HIV testing.

A parallel trial will target metropolitan areas, including Jackson. “The PrEP@home kit is the cornerstone of these two studies,” Brock said.

Another important strategy being studied is barriers to starting PrEP as soon as person seeks care at a clinic for sexually transmitted infections. A new study, “Rapid PrEP Initiation,” will examine the implementation of linkage to PrEP and issuing the prescription for Truvada on the same day that patients are tested for an STI. It is designed to optimize PrEP uptake, time to PrEP initiation, and retention on PrEP, Beauchamps said. This study will be conducted at Express Personal Health.

Access to culturally competent and quality care, Mena and Brock say, is critical if those who need it the most are going to remain disease-free. “We have people who come to Jackson who live many hours away because of privacy concerns or lack of a PrEP provider nearby,” Brock said.

“How do we overcome the barriers? That’s why it’s important to do things like this. We are hopeful that these trials will pave the way for a new model of care that mitigates the need for a visit to the physician’s office for things such as HIV preventive treatment.”