Caring for COVID-19 patients: Teamwork, time make difference

Do not say the “Q word” on the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s all-COVID-19 intensive care unit.

The lack of noise on the 20-bed medical ICU, or MICU, might beg the question: Is it quiet today? What might happen over the next 10 minutes belies that.

“We don’t like that word around here. It brings bad luck,” said Tony Sistrunk, a MICU charge nurse. “As soon as you say it, things might pop off. That’s a word we take out of our vocabulary.”

When quiet turns into what some on the unit would call chaos, it’s nothing like the scenario Americans saw on television of overwhelmed, overcrowded hospitals in New York City, and of front-line caregivers publicly begging for personal protective equipment amid a worldwide shortage.

Instead, a flurry of activity could entail patients from the all-COVID wing of the second floor of University Hospital being moved to the MICU if their condition deteriorates, or to the cardiovascular ICU, which devotes half its beds to COVID-19 patients, depending on the need.

It could mean providers weaving around each other to congregate by what some call the “brains” outside many of the rooms: a ventilator, plus machines dispensing insulin to diabetics, heparin to those in danger of blood clots, propofol to keep patients on vents sedated, and fentanyl to cut excruciating pain patients can endure when providers must roll them in their beds.

“I’d call it life support,” critical care physician Dr. Andy Wilhelm says of the monitor collection. “It’s more than the vent. It’s all of it.”

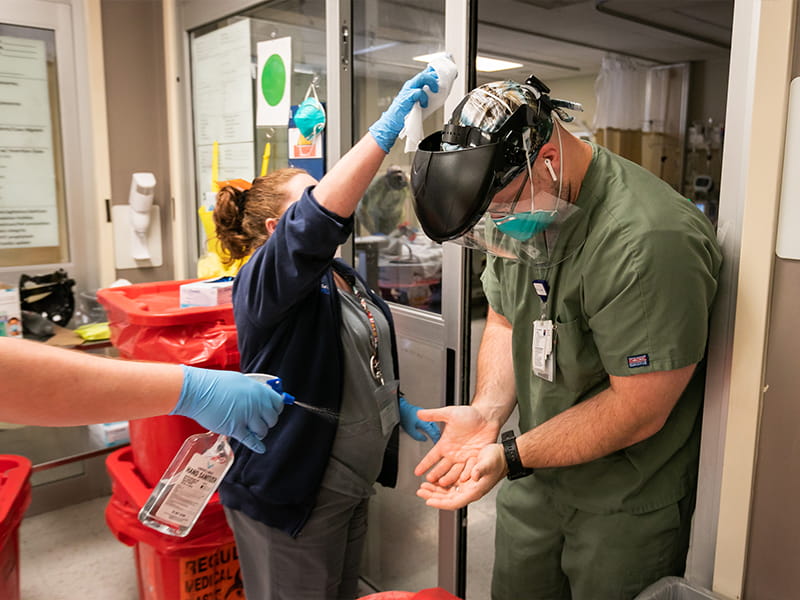

It could mean teams hustling up and down the unit, flipping patients from their back to their belly or vice versa. It could be caregivers swiftly getting in and out of a room, then being met outside the door by a fellow provider who helps them “doff,” or remove their contaminated gloves and gowns, and clean their plastic face shields with a disinfectant.

It requires selfless teamwork, knowing who is where and when, a shout down the hall to gather up the people resources needed to lift a patient or complete a procedure.

“It takes so many people,” said Allison Moore, a registered nurse on the MICU for the past 10 years. “You have to gown up and protect yourself, sometimes very quickly.”

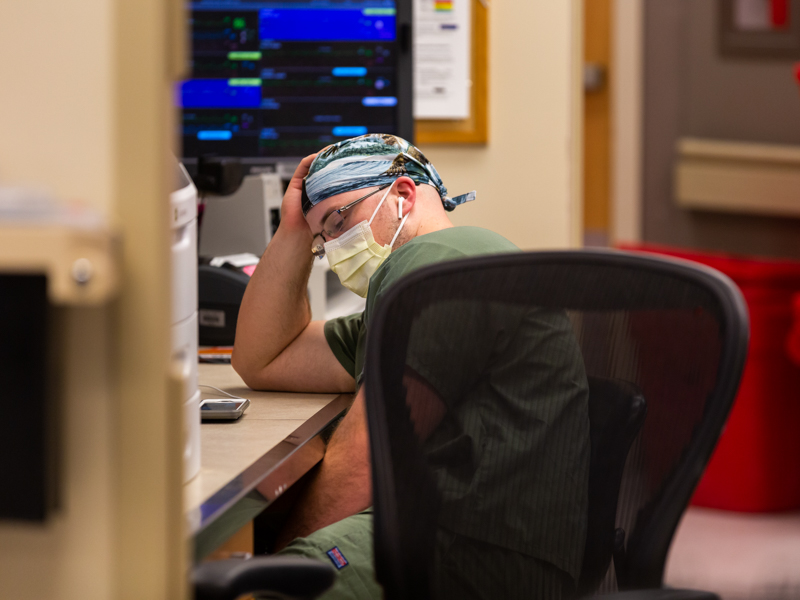

What’s often absent in patient rooms is conversation. Those on ventilators are heavily sedated and paralyzed. The rest are often too desperately ill to have the interaction with their nurses that builds trust and friendship.

Registered nurse Margaret Workman gets creative in being stand-in family for her 2 North patients. Providers don’t enter their room unless it’s necessary, but Workman calls or FaceTimes them on their cell phone.

“These people are truly isolated,” said Workman. “I take care of my patients as a whole – physically, spiritually, mentally. I worry that because of this virus, I can’t be who I want to be as a nurse.

“There are days where I don’t feel I met all their needs, but then they tell me I did everything they needed.”

On the MICU, “we don’t really get to know the patients themselves,” said nurse manager Ashley Moore. “We learn everything about their bodies, but we really get to know their families. We learn about our patients through the families when we keep them updated on FaceTime.

“We are cheering for the patients to get out of here, but they might never know us.”

“It’s sad watching them. You say prayers for them,” Allison Moore said. “I held one man’s hand for a long time, and when I got back to him later, he was dead.

“But one of my patients might get extubated today. I’m hopeful for them.”

A virus with many faces

Wilhelm wishes everyone in the public could see what he sees. The days when three or four patients in the MICU die “are tough,” he said.

The time in May, when both the MICU and the 20-bed cardiovascular ICU were totally filled with COVID-19 patients, was a challenge, with Medical Center front line caregivers doing a yeoman’s job despite an ever-changing understanding of the monster.

“We think of COVID as a respiratory disease, but it’s not,” said Wilhelm, medical director of the MICU. “It causes multi-organ failure. One or a combination of both will land you in the ICU.” Ditto for other complications, among them kidney failure, stroke, brain bleeds, diabetes and blood sugar gone wild.

“We had one person with severe muscle aches and kidneys that had shut down, but their respiration was great,” Wilhelm said. “There are so many clinical manifestations.”

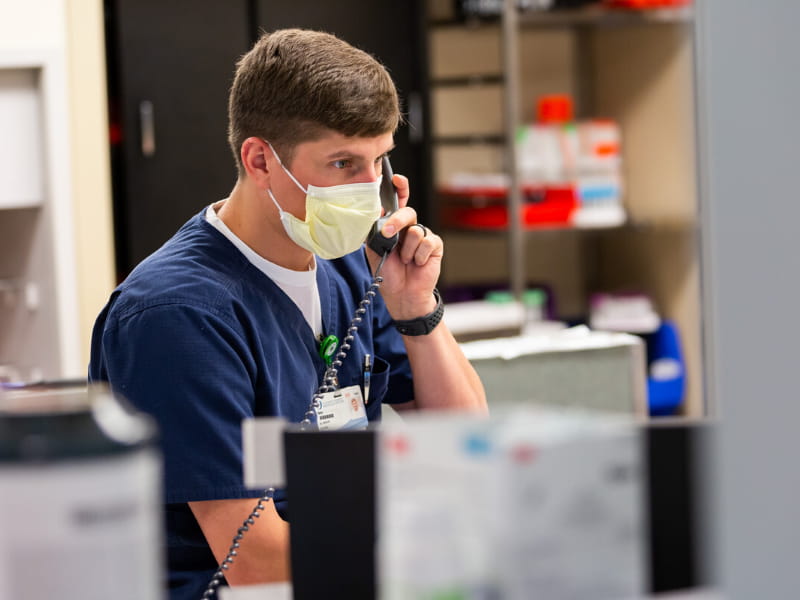

On a recent Tuesday morning, there are three unoccupied beds in the MICU. “Bed 3 was a PUI, but they’re confirmed now,” Sistrunk said. A PUI, or person under investigation, is awaiting results of in-house testing for the virus.

“Beds 1-4 are COVID positive. Six through 16 are positive. Seventeen is a PUI. Bed 20 is positive,” Sistrunk said. “If 17 is negative, we’re getting that patient out of here. We won’t want them to be accidentally exposed.”

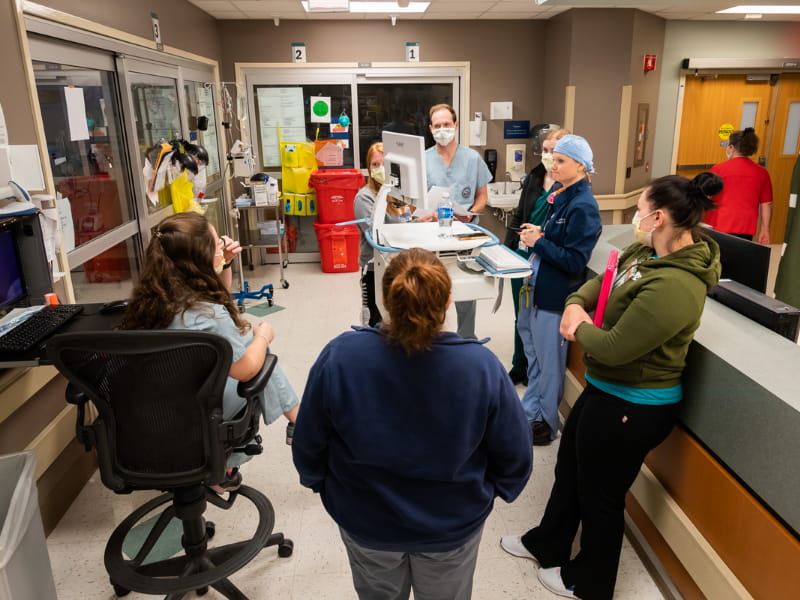

Shortly after 9 a.m., a team of caregivers led by pulmonary physician and attending Dr. Jessie Harvey begins rounding from room to room, mostly staying in the hallway. The group includes a cardiology fellow, an intern, a pharmacist, a nurse practitioner and a social worker.

They stop at the room of a middle-aged patient with a history of stroke who was intubated earlier in the month. Caregivers twice have tried to remove the patient from vent support, without success.

The next patient, also middle-aged, went on a vent the day before. “I don’t know if (the patient is) getting better, or if (the patient) just likes being proned,” pulmonary nurse practitioner Shannon Moffett told the team.

The patient is oblivious to the proning, a maneuver in which a person is carefully flipped from their back to belly down. This patient’s condition could be improving because proning takes weight off the lungs in hopes of making it easier to breathe. “It lets the alveoli in the lungs open up and get the crud out,” Sistrunk explained. “If you’re on your back, nothing’s moving.”

Proning ventilated patients is a process. “Three or four of us get together, put on our PPE and go into the room,” said Sistrunk. First, they don a pair of surgical gloves. Second, a yellow disposable hospital gown. Third, a second set of gloves. Fourth, a N95 mask. Fifth, a large plastic face shield.

They cover the patient with sheets and tightly roll the edges along the patients’ sides. “You roll them up like a burrito,” said registered nurse Scott Bridges. That’s for their protection and for a minimum of movement on everyone’s part.

“We put a clamp on the hose on the vent, unhook them, grab the edges of the sheets and flip them over, and hook them back up,” Sistrunk said.

They leave their top gloves behind and swiftly exit. Registered nurse Will Parish is waiting. He sprays down their gloved hands with alcohol and drops a clean pair into their hands to don as they hustle to the next patient to be proned.

“You can’t touch anything. You can’t stop,” Parish said. So long as the patients don’t have secondary infections that could cause cross-contamination, the proning group doesn’t have to change their other PPE.

Patients stay on their stomach for 16 hours and on their back for eight. Every two hours, the team “swims” them, turning their head in one direction and raising an arm above their head. That reduces their risk of damage to nerves that control movement and sensation in the shoulder, arm and hands, Sistrunk said.

A significant majority of vented patients will die, Sistrunk and Wilhelm said. Before they are intubated, “you have to make sure they get to speak to their loved one first,” Sistrunk said. “We’ve had some that have come off the vent, but not as many as we’d like.”

Cautious hope in clinical trials

The rounding team’s next patient, also middle-aged, is on the antiviral medication Remdesivir, which in clinical trials has shortened the time to recovery for some who are severely ill. The drug became available at UMMC in mid-May.

The patient’s respiratory status has improved, Harvey told the group. “Most people who come here end up not doing well, but because we’ve dropped this patient to 70 percent (oxygen), and then 60 percent, that’s good.”

A young adult on the unit this day is on a ventilator, but isn’t getting worse. Sistrunk said the MICU earlier cared for a young adult who was diabetic and had other comorbidities. “That patient didn’t make it,” he said.

Posters identifying patients as part of UMMC’s COVID-19 clinical trials dot the glass windows of the rooms. Before they go on a vent, selected patients are asked if they’d like to take part, and many say yes, Wilhelm said. They’re either getting a placebo medication or the real thing. Thin dark plastic that calls to mind a hair scrunchie covers the IV line and part of the IV packaging to keep its status blind.

As information trickles out about promising new treatments, Medical Center caregivers intercept it. “We are scouring social media. We are scouring news media,” Wilhelm said.

When news broke last week of a United Kingdom study that suggests the common steroid dexamethasone reduces deaths among seriously ill COVID-19 patients, “we formally added it to our treatment recommendations that day,” Wilhelm said. “Other studies have given it a little more validity as well.”

Dexamethasone is the decadron shot you get from your provider for severe allergies or asthma, arthritis or even some cancers. “Before Tuesday, it was easy to get,” Wilhelm said.

There’s not yet proof that any of the drugs being touted as possibly shortening the duration or improving mortality actually do that, Wilhelm said. “I say ‘may help’ with caution,” he said. “We don’t know if it’s because of the drug or because they were going to get better anyway, or if it was because of the therapy we were giving them.

“If the potential benefits outweigh the risks, we’ll probably try it.”

Heroes for the long haul

COVID-19 patients who need hospital support but not ICU care fill the 32 beds on 2 North. This day, all but a couple are in use. If they’re at max, the overflow goes to 2 South. “At one time, they were in the 20s, and we were full,” said Jamie Hill, a nurse manager on 2 North.

Pediatric patients go to the children’s hospital or its ICU. There have been no deaths and a relatively low number of positives and PUIs, said nurse manager Shelly Craft.

Her only COVID-19 patient that day, a PUI, “needs just a little higher level of care” than they would be receiving on a regular floor, Craft said.

Deaths on 2 North are significantly less than in the ICU. “How they feel and their symptoms determine when they leave,” Hill said. “We don’t discharge them through the front door. We have their driver come to a special door, and we educate them on caring for the patient.”

2 North is bustling. Fronting the nurses station is a huge cart of disinfectant wipes and PPE. It helps staff keep track of what’s running low and helps ensure none of it leaves the unit.

As COVID-19 providers stay in motion, so do others who support them. That includes the health care heroes who dispose of hundreds of pounds of PPE and other virus-contaminated waste. Nurses place bags of waste into large red plastic totes in each patient room, then move the tote just outside the door. With gloved hands, housekeeper Bill Culpepper lifts the totes onto a long dolly that holds nine containers, three deep, and leaves empty containers in their place.

He pushes the heavy dolly to a loading dock and lines up the totes in a large trailer. Culpepper does that 10 or more times per shift.

“I got Jesus,” he said. “I’m not scared. I’m proud to do what I do every day.”

As the summer progresses, “I expect we’re going to see more younger people admitted. They’re going back to their jobs and lives and not being as cautious,” said Dr. Jason Parham, director of UMMC’s Division of Infectious Diseases. “I don’t see a whole lot of signs that things are going to get a whole lot better

“I think we are preparing the best we can.”

The virus could be a part of life for two and a half years, Wilhelm said.

“We’re shifting into a maintenance phase,” he said. “We have to look at what the world is doing. We have to know that we provided the best fundamentals of critical care, and if someone doesn’t make it, we practiced the best medicine we could.

“Our goal is to treat and support our patients through this. Sometimes we can. Sometimes we can’t.”