From STEM to stern, research lab is all-female, all-diverse, all the time

Haley Williams had never seen anything like it before.

And, as some people are apt to do when they’re bursting with news, she had to call someone – her mother: “I said, ‘Mama, I’m in a research lab with all women.’”

This certainly was a newsflash, considering that only 30 percent of the world’s science researchers are women, while in the U.S. the figure is only 28 percent for those in science and engineering: two of the four pieces that add up to the education curriculum known as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math).

Yet, here in a lab at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the percentage is 100: six out of six, including three women who are African American – another rarity – but not counting the lab’s Cuban-American supervisor of business and clinic operations, Yilianys Pride.

“It was serendipitous; it just sort of happened,” said the lab’s principal investigator, Dr. Sarah Glover, “and I’m thankful, because when you have a diverse lab, it’s not just about the science; it’s also about caring for your friends and neighbors.”

In this case, some of those friends and neighbors are among minorities who are often overlooked in tests for medical treatments for chronic ailments, such as inflammatory bowel disease, the bailiwick of Glover, professor and chief of the Division of Digestive Diseases at UMMC.

African Americans, for instance, represent 13 percent of the U.S. population, but a recent review of studies showed they made up less than five percent of clinical trial patients for investigations of such IBD’s as Crohn's disease, said Glover, citing figures from one of her grant applications.

Even worse, African Americans with Crohn’s are more likely to be hospitalized than Caucasians, and suffer poorer outcomes.

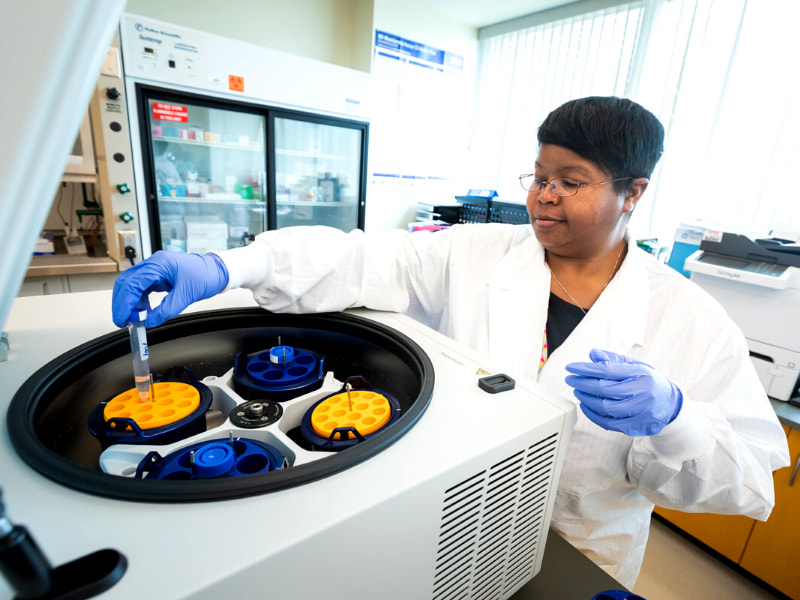

“It’s important to have more minorities participating in clinical trials because, sometimes, our body reacts differently to certain treatments, compared to someone who is Caucasian,” said Dr. Tanya Robinson, assistant professor of digestive diseases, and manager of the lab, located in the Guyton Research Center.

“It’s also important because you can get a better look at the disparities in the rate of such diseases; those include higher rates of diabetes among African Americans and prostate cancer among African American men.”

Diversity in the lab poses another potential plus: peace of mind, Robinson said: “I’m hoping that, with more minorities who are researchers, we will be able to bring more of them to clinical trials as patients.

“If they can see another minority doing research or practicing medicine, it may ease their fears about participating.”

Taylor Christian of Columbus, for one, said no female physician has ever treated her – or even an African American one.

“I never really thought much about the fact that they didn’t look like me, but to many people, that is important,” said Christian, a third-year medical student who stores, ships and processes samples for the lab’s study of COVID-19’s impact on the immune system, gastro-intestinal disease and more.

“I definitely believe it’s important to show people with a minority background that, even if the people who traditionally have certain careers don’t look like you, that shouldn’t deter you, if that’s what you want to do. For me, working in this lab has been kind of a confidence booster.”

For Robinson, a Jackson native, the hope of bringing more African Americans to research is also personal: At least two of her loved ones have diabetes; she has lost several to breast cancer.

“Also, autoimmune disease runs in the family,” said Robinson, who holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Jackson State University, a Ph.D. in microbiology from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and postdoctoral fellowship credentials from the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

“That’s why I was originally interested in becoming a doctor. But after being part of two different research programs, that sealed it: I realized I can also contribute to the cure of diseases this way; and research fits my personality. I just love it.”

It’s also personal for Williams, a volunteer lab technician who has applied to the School of Medicine at UMMC. “I want to help my community, and underserved communities in particular by researching ways to fight preventive diseases,” said the Smithville native. “I want to understand why some affect certain populations more than others.

“But I did not expect everyone I would be working with to be a woman, or to walk into that lab for the first time and see that Dr. Robinson is a woman of color. Then Dr. Glover walked into the room, and it was, ‘Oh, my gosh.’

“Before that, I didn’t think I would be able to do research once I became a physician. I thought, ‘Something will have to go.’ But Dr. Glover and Dr. Robinson have showed me that you can do it all. This is like a dream job.”

It was Robinson who pulled together the equipment for the lab at the behest of Glover, who arrived at UMMC from the University of Florida in Gainesville in early 2019. She also helped assemble the staff, most, if not all of whom, reached out to Glover based on her projects or reputation.

“Tanya is a gem,” Glover said. “There are definitely fewer Ph.D.’s who are women and African American. So I’m lucky to have found her. She understands that disparities exist. She brings a certain passion to the science.”

Robinson and Glover also brought in Dr. Anna Owings of Nashville, an internal medicine resident in her final year of training; and Hannah Laird of Starkville, a second-year medical student and lab volunteer for the COVID project.

For Owings, diving into research was also personal. She is “very close” to someone with Crohn’s disease: her identical twin sister. It was Glover’s focus on Crohn’s, in part, that drew her to this lab.

“Dr. Glover has been very welcoming to projects you come up with, and very supportive,” Owings said. “And the fact that our group is so diverse has helped us come up with many different types of ideas. If we all had similar backgrounds, I don’t know if we would have that advantage.”

For Laird, research is especially appealing to her as a future physician. “I always liked figuring out how drugs work on people, which you do in clinical trials,” she said.

“So I wanted to see how it is to be a physician-scientist, not just a physician. And Dr. Glover is all of that. She wants to lift all of us up, and she really wants to have a diverse group working in the lab.

“Haley and I both have different upbringings and life experiences, but it’s really cool that we now have the opportunity to do the same thing. And Dr. Glover has allowed it to happen. She has helped me branch out and meet different people.”

One of those is Pride, born in the Cuban province of Villa Clara, where she grew up playing “doctor and pharmacist” in a country where “everyone has a right to health care,” she said.

In Cuba, Pride earned a bachelor’s degree in biology before emigrating to Mexico with a visa to work in a research lab, and then to the United States.

“Coming to America was like [being] born again,” said Pride, whose search for more work led her to Texas and eventually to Miami. “I knew how to read and write English, but I had to learn how to speak it,” she said. “And I had to learn much more, such as how to drive.” And how to find another job in health care.

Her quest led her to Jackson, where she was hired to help in a sleep deprivation study for the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at UMMC; and then, for eight years, as an auditor in the Mississippi State Department of Health.

There, at MSDH, Pride “fell in love with the administration part of health care” – to such a degree that she earned another one: a Master of Healthcare Administration at Belhaven University.

When Glover started her own search for a Research Specialist/Patient Navigator, she found Pride, recently promoting her to her current job in the division. Even so, Pride is still working also as patient navigator for the lab, where, she said, “we all bring a lot to the table.

“I love it. I am passionate about what happens behind the scenes in the patient care industry, and this is the perfect setting.

“Here, we are all different, but we are equal; we are all women – that’s the part that is equal. At the same time, we have our different cultures, our different backgrounds. So it’s lovely.”