3D printed models save time, money in operating room

A routine root canal was what brought Susan Browning, of Laurel, to see her dentist Dr. Chad Harris. He noticed a small spot on her gums that was bleeding and delayed the procedure in order to treat the spot with antibiotics.

It didn’t go away.

“You know, it was nothing obvious,” Browning said. “Then all of a sudden it was.”

The spot rapidly grew and spread. Browning said her gums began to look rough and bumpy, abnormal. Harris referred her to an oral surgeon for a biopsy. Browning and her husband of 45 years, Raymond, traveled to Hattiesburg to have the biopsy, and less than a week later the couple received the news.

Browning said she was told, “It’s cancer. It’s invasive, and it’s aggressive, and you have to do something now.”

They had two options: travel to Birmingham or travel to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson for treatment. They were told of a new oral surgeon who had recently joined the faculty at the UM School of Dentistry and was “super-duper good.”

“[The surgeon] talked really highly of Dr. Velasco,” Raymond said. The couple decided that Browning would travel to Jackson to receive treatment.

Dr. Ignacio Velasco, assistant professor of oral and maxillofacial surgery and pathology, earned his dental degree from the Universidade de los Andes in Chile. He completed an internship and residency program in oral and maxillofacial surgery at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Center, working primarily with oral oncology patients in his last few years there.

This experience sparked his interest in oncological surgery. Velasco applied for a highly sought-after fellowship at Peking University Hospital of Stomatology in Beijing, China. The fellowship was sponsored by the International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Out of a large pool of surgeons from around the world, Velasco was one of two selected for this fellowship specializing in head and neck oncological surgery.

From Browning’s first visit with Velasco to her second, the cancer had grown.

“It was like a little monster spreading,” she said.

At first the Brownings were overwhelmed by the prognosis, but with each test and scan the situation looked less bleak.

“If my neck was clear, it was a better chance,” Browning said. “If my chest was clear it was an even better chance. Each one cleared boosted the odds [of survival].”

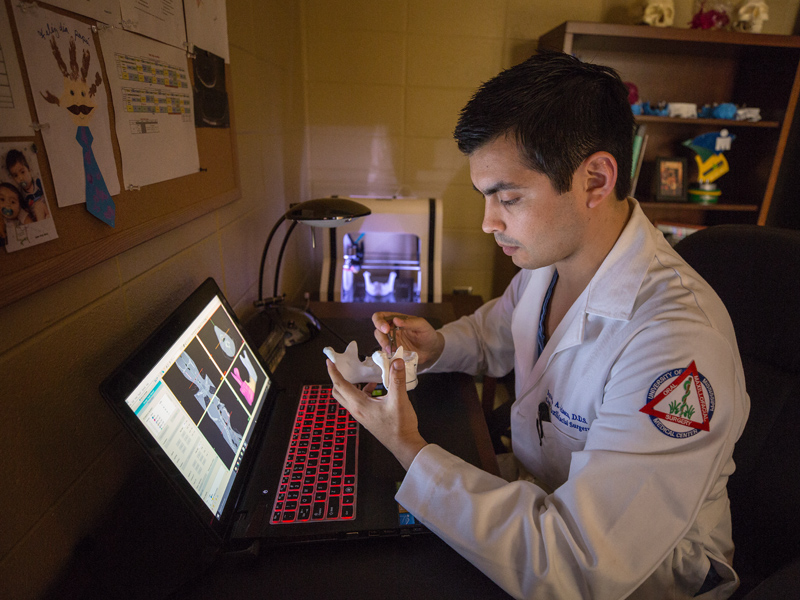

“I think it was the second time we came back, he had the 3D model,” Raymond said. “He showed us where he was going to take out bone and what he was going to do. They did what they call a partial removal of the bone.”

“They shaved it down and left just enough of the bone to anchor the titanium,” Browning said.

Velasco routinely used 3D printing to assist with surgery planning and execution during his fellowship in Beijing. Since arriving at the Medical Center last September, he has introduced benefits of the technology to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and it’s saving both time and money for UMMC and improving patient outcomes.

“I have been using this technology to create my own surgical protocols for three or four years,” Velasco said. “It helps you understand in a better way the disease or trauma.” He said it is also helpful for showing patients what will be done during surgery and teaching residents in an academic setting.

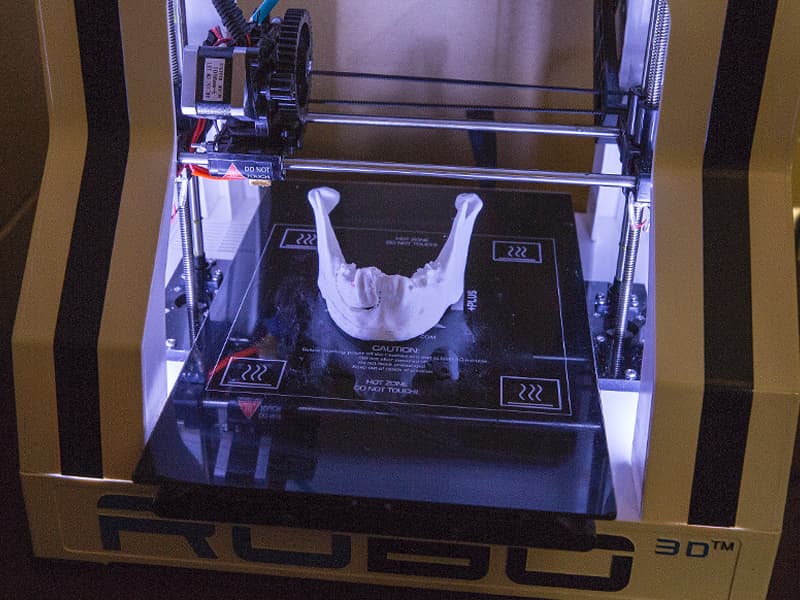

Virtual surgery planning and computer aided design has been a useful tool for oral and maxillofacial surgeons for some years, but it takes time and costs money. In cases that require rebuilding the jaw from a section of a patient’s fibula, the hospital is charged as much as $15,000 for computer images that are two dimensional representation rather than an actual three dimensional model. After the initial cost of the printer – in this case about $500 – a printed 3D model created by Velasco overnight in his office costs in the neighborhood of $10.

Velasco said that the real savings comes about in the operating room.

“[Implants] are very strong plates made of titanium. If you don't have the model, you must bend the plate in the middle of the surgery,” he said. “You have the patient there – it's an open surgery. You have to bend the plate and try to see if it a good fit. It can take half an hour or forty-five minutes.” That’s more time that the patient is under anesthesia and more time in the operating room using resources.

The 3D printed models can be used to shape titanium implants to fit the patient’s face before surgery, saving time in the operating room.

“The longer the patient is on the operating table – it doesn't matter if it is a maxillofacial surgery, vascular or orthopaedic surgery – the longer operating time is correlated with an increase in anesthesia complications and wound complications,” said Dr. Ravi Chandran, associate professor and chair of oral and maxillofacial surgery and pathology.

Chandran said that another factor is the time it takes to receive the image models from the third party provider. He said that the process of ordering the images, proofing for accuracy and receiving the final product can take at least a week to 10 days. Trauma and cancer patients often don’t have that time to wait.

“This is all delaying the patient care,” Chandran said. “The typical window for repairing facial fractures is one week.” With the in-house 3D printing, a patient that comes into the emergency department with facial trauma on a Friday night can be scheduled for surgery as early as Monday morning, he said.

Chandran said that, for now, the technology works best for cancer and trauma patients. The models do not have fine enough detail to be used for orthognathic or corrective jaw surgery since these surgeries require precision down to a few millimeters.

“Currently we have capabilities to tackle trauma and pathology cases, but for orthognathics, we are going to need expensive equipment and a little more training on our end,” he said.

That brings up the downside to introducing the new technology to the Medical Center: It’s a learning curve. Velasco does not see that as a big hurdle.

“It takes some time to learn the software, but it is no more than a couple of months.”