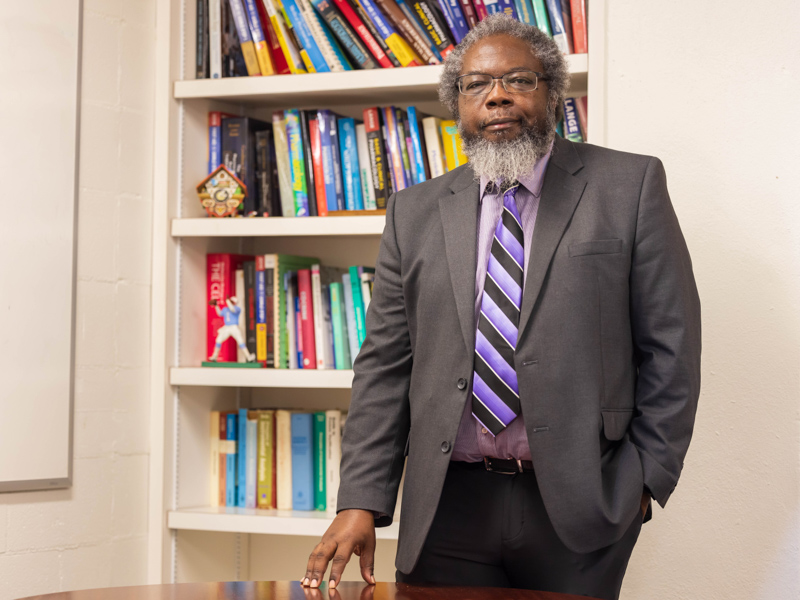

Smith to the nth degree: Pharm professor discovers the right chemistry at work, in life

Editor’s Note: This is an edited version of the Faculty Profile published in the Fall 2023 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the medical school alumni magazine.

When Dr. Stanley Smith was 3, his grandmother found a blister on her foot that became infected.

She had diabetes; the infection spread, but the local hospital in Meridian wouldn’t treat her gangrenous leg, Smith said, “and sent her home to die.” She lived another five years.

She survived because of surgeons at the University of Mississippi Medical; she lost her leg, which saved her life – a life lived out in a wheelchair, where Smith would climb up in her lap and hear her sing “Amazing Grace.”

Sue Willie Bell’s story is one reason Smith returned to UMMC one day and stayed. There are others, including his mother’s cancer battle, enduring friendships and a sense of belonging.

He arrived at UMMC as a researcher, but his artistry as a teacher has also been honored. For Smith, the place is a gift – made possible in part, by a man with a beard as white as snow.

Wheelchair songs

“He’s meticulous,” said Dr. Barbara Alexander, professor of physiology and biophysics at UMMC, who navigated graduate school with Smith. “If Stan did something scientifically, it was going to be rigorous to the nth degree.

“And he’s just a good guy. Stan is just Stan.”

You have to be pretty good with numbers to be a professor of pharmacology/toxicology, which is what Smith became instead of a sports statistician: his former dream. He’s come a long way from Longview, near Starkville – on “the other side of the middle of nowhere.”

His dad, Archie Lee Smith, made railroad ties, shaped two-by-fours in sawmills, drove Coca-Cola trucks and labored at a furniture company. Stanley Smith admired his father, but had other plans for himself – plans shaped, in part, by his father’s visits to the doctor.

His dad’s “rural, Southern dialect” was difficult for some to understand. Stanley Smith, “fluent in Deep South,” served as an interpreter of sorts, he said.

“The doctors who were best for my parents were good communicators. So, I developed a desire to be a patient advocate, especially for people like my parents, people from a rural background who may not have a lot of education.” He was the first in his family to attend college.

Born in 1965, Smith was the youngest of four children of Catherine Smith, “one of the smartest people I’ve met to this day,” he said.

“If she had had half the opportunities I had, the world would be a much better place.” She was a housekeeper – which may have helped save his grandmother.

Around 1968, Sue Willie Bell nearly died. Smith isn’t sure why the local hospital wouldn’t take her, “but we were so poor, we wouldn’t have been able to pay for the treatment.”

Lorene Montgomery, who employed Catherine Smith as a housekeeper, “piled my mom and my grandmother into her car and drove to Jackson,” Smith said. At the Medical Center, doctors added five years to his grandmother’s life.

That’s why her grandson is able to remember her: “I’d go to her wheelchair, and I was protected. If I was in trouble, she would sing to me.”

She was not the last member of the Smith family the Medical Center would save.

Christmas in the lab

All Dr. Bob Koch lacked to complete the picture were a bundle of toys and a red suit.

“He had a long, white beard and looked like Santa Claus,” Smith said. “And he made me become a better person; he believed that your reputation meant something.”

A Mississippi State University faculty member, the biochemist was a supreme influence in Smith’s life. After a recommendation from a counselor at Starkville High School, Koch enlisted Smith, a sophomore, to work in his lab.

“From the moment I stepped into that lab, I knew what I was going to do. I became the consummate lab rat,” Smith said

Soon, Koch asked Smith to fill in for him in a biochemistry class. At 17, Smith was schooling post-graduates. It must have felt right: Decades in the future he would be praised by his students at UMMC.

“I’ve wanted to be like one of those people who had made such a difference during my life at UMMC,” Smith said. “That’s maybe why I go the extra mile with my students.”

One of those, Isabella Kelly, a third-year medical student, said, “He’s just a genuine person. He loves what he’s doing and loves the subject he’s teaching. And, honestly, everyone loves him.”

His enthusiasm makes the torrent of classwork easier to swallow, said Chris Glasgow, another M3. “There were many lectures I showed up to that I would have normally skipped had it not been for his excitement.

“If he sent an email, there was a 100 percent chance that the word ‘YAAAAAAAAAAAAYYYYYYY!!!’ was in there.”

Smith’s ability to reach students has been acknowledged by, among others, the Carl G. Evers Society, Trailblazer Award, and Nelson Order.

But, as he sharpened those skills decades ago under Koch’s guidance, Koch’s own abilities suffered. His short-term memory failed him; where Smith was concerned, Koch’s kind heart never did.

Hoping to afford college, Smith sought financial aid; he was awarded with apathy.

“Dr. Koch walked me back to that office and said, ‘I want to see how to get this young man into college.’ The attitude there changed,” Smith said.

Smith majored in biochemistry at MSU. Because of work-study, grants and scholarships, he didn’t need a loan.

He finished in 1987 and decided to strike out for Jackson for graduate work – the beginning of a journey made possible by Koch and a car the color of sunshine.

A basket case

Dr. Steve Case, who would retire as associate dean for medical school admissions, taught molecular biology in 1987, the year he invited Smith to UMMC.

“Dr. Koch drove me to Jackson in a yellow Volkswagen with a stick shift,” Smith said.

At UMMC, Smith became Case’s graduate assistant. In the lab, he synthesized a gene that enabled him to understand how fly larvae make their own housing with silk proteins from their salivary glands.

He was making a name for himself; but, when his mother was diagnosed with cervical cancer, it was hard to feel joy.

“I was a basket case,” he said. His family still didn’t have money and had to find a place to treat his mom.

“The Medical Center was the last hope for those who were in need,” he said. Students and faculty helped get Catherine Smith to the right oncology team. She endured surgeries, radiation treatment and more.

This was in 1993. Two years later, Smith had a PhD in biochemistry and an undying allegiance to the Medical Center.

Five years after her diagnosis, his mom was pronounced cancer-free. Dr. Jeffrey Hudson, an OB-GYN resident at the time, broke the good news.

“He came to my mom’s room because he thought he should be the one to share this with her,” Smith said. “These are the kind of people who make UMMC the special place that it is.”

When he finished his PhD, he was going to stay. He thought.

Moving on and marriage

If he wanted to join the faculty, it would be better if he first trained awhile somewhere else, Smith learned.

“Awhile” became seven years. At the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, during a second fellowship, he became immersed in pharmacology.

By then, Catherine Smith had been cancer-free for four years, but her son wanted to live closer to her. After Bethesda, he returned to UMMC to conduct research and teach principles of pharmacology and toxicology. That was August 2002. This year, he became a tenured professor.

Two years before returning, his mom’s condition worsened from side effects of radiation therapy, and she needed surgery; 2000 was the same year his sister, Dorothy Ann Johnson, died of colon cancer, at 48.

Years later, in a 2018 Medical Center article, Smith urged others to get screened for colorectal cancer. “It is a pain-free procedure and gives you an answer,” he wrote. “You … can move on with life until the next screening.”

Certainly, Smith has had to move on. In 2015, he met Anne Louise – now known as Anne Louise Smith. After their wedding, he became stepdad to two “wonderful bonus daughters.”

“I’m a scientist, but I can’t put a quantification on it or an algorithm; I just knew. At age 50, I had found the person I was looking for,” he said, “the love of my life.

“I saw in her the same strength and capacity for love my mother had.”

Catherine Smith died, in 2009, 16 years after her diagnosis. “Those were years I might not have had with her if not for the actions of people here at UMMC,” her son said.

“So, I tell students, ‘You will literally help change people’s lives – be proud of that fact.’

“After 20 years here, I have seen so many of them do great things,” said the man with the long, white beard.