Medicine still mending from Jim Crow era

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published in the Summer 2019 edition of Mississippi Medicine, the medical alumni magazine.

Despite its many accomplished practitioners and pioneers, medicine in Mississippi also has a sinister history of intransigent racial discrimination the state is still trying to overcome.

This history shadowed not only individual practices, but also the state’s most important institutions, including the University of Mississippi Medical Center and the state affiliate of the American Medical Association.

Numerous physicians were witnesses to, or architects of, the events that helped reverse the worst abuses of racism and face the challenges left in its wake.

Some were motivated by the image of a mortally wounded man struck down in front of his family; several have deep connections to the Medical Center.

Here are the recollections and observations of five.

‘We were angry’

Like smoke and fire, those events were not unrelated.

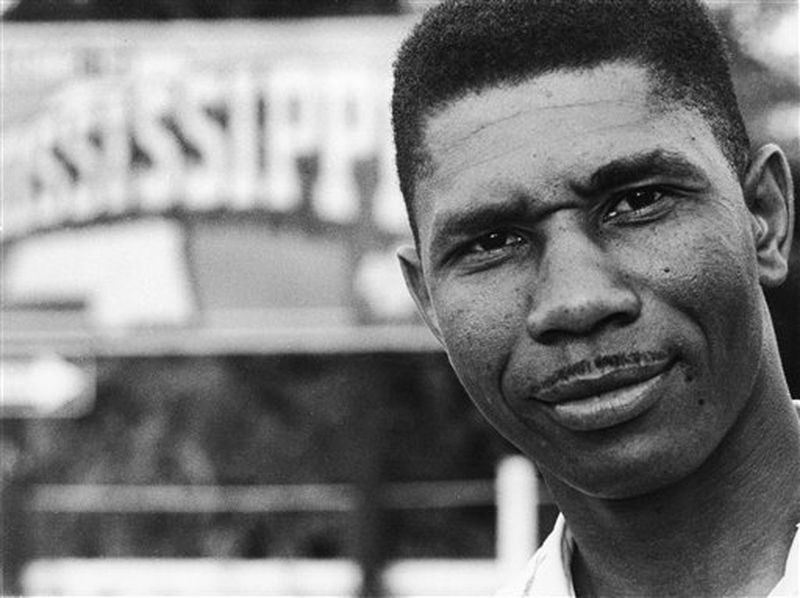

Evers, the NAACP field secretary in Jackson, had been gunned down in his driveway with a hunting rifle.

But the trajectory of the bullet that took Evers’ life did not end its flight that summer night 56 years ago. However inadvertently, it helped shatter the forces of discrimination across American society – not least of all, inside one of the last strongholds of discrimination: medicine.

“Medicine is one of the most elite professions in America,” said Smith, a Jackson physician and one of the activists who helped quash the racial apartheid practiced in professional medical societies, including the AMA and its affiliate, the Mississippi State Medical Association.

“I’m sure that’s why I wanted it, why I wanted those barriers broken down,” said the Terry native. “But, despite the racism, there were people who taught me, from home to grade school to high school, that we are all created equal, and I believe that.”

As his father had said: “‘All people put their britches on the same way.’”

For a long time, though, doctors weren’t allowed to put them on in the same changing rooms, or eat in the same dining rooms, or see patients in the same hospital rooms.

The root of this prohibition can be traced back to the 1800’s, when a Confederate general, J.M. Keller, M.D., led efforts to deny AMA membership to blacks, an injunction that persisted through much of the 20th century.

Yet, you had to be an AMA member to be on a hospital staff. Meaning that a black physician couldn’t put his own patients in a hospital, at least not in a white-operated, segregated one – which most of them were.

On top of that, throughout the civil rights era, AMA officials denounced government attempts to improve health care access to blacks as “socialized medicine.”

Eventually, in the 1950’s and 1960’s, many black physicians, and some who were white, reached a breaking point, a moment of moral clarity when endangering their livelihoods and their lives seemed less onerous than risking their self-respect and their patients’ health.

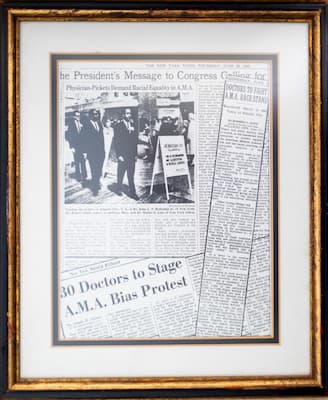

There was nothing they could do about Evers. But there was something they could do about the reason he died. So Smith traveled to Atlantic City, New Jersey, with a chip on his shoulder and a picket sign in hand. He and a handful of other physicians posted themselves outside the Traymore Hotel, where the AMA was in session.

The press was there to record the demonstration. “It brought national attention to the problem,” Smith said.

Among the handful of physicians protesting against the AMA, Smith was the only one from the South, he said. “I was told it would be the end of my career. But we were angry. We didn’t give a shit at that point.”

‘I don’t want you’

“I haven’t joined to this day,” said Barnes, now a UMMC emeritus associate professor of obstetrics-gynecology.

A medical school graduate of the predominantly black Howard University in Washington, D.C., Barnes did join what had been the all-white Delta Medical Society while working as a general practitioner in Greenwood during the early ’60s. She was allowed in because of her credentials, she said. But not all the way in.

She had to stay in the kitchen, more or less. The white physicians put an “s” by her name, for “scientific member.” She could meet with them, but could not eat with them.

“I said at the time that there are many things you can forgive,” she said.She could forgive the white physicians for putting an “s” by her name. She could forgive the white patients who would refuse her services.

She could forgive God or fate or whatever it was that took the life of a boy names James, who died in the infirmary of the boarding school she attended as a little girl, wrenching from her a vow to become a doctor – “so James wouldn’t die.”

But, in 1963, “I said, ‘I’ll never forgive Mississippi for killing Medgar Evers.’”

‘Lives in parallel’

DeShazo, former professor of medicine and Billy S. Guyton Distinguished Professor, and chair of the Department of Medicine at UMMC, joined the movement toward racial reconciliation years ago and became a chronicler of civil rights pioneers like Smith, Barnes, Dr. James Anderson and more.

Many of their stories are told in the book he edited: “The Racial Divide in American Medicine: Black Physicians and the Struggle for Justice in Health Care” (2018).

“Much like blacks and whites had long lived lives in parallel, black and white physicians had practiced in parallel,” deShazo said.

A certain degree of apartness persists, not only in Mississippi: About 22 to 23 percent of Black/African-Americans in the U.S. said they were not always able to get care, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported in 2017. The percentage is twice that for White/Caucasians.

Many attribute the imparity, in part, to medicine’s long history of racial exclusion – among them, deShazo, who witnessed the tragic upshot of those divisions in his own home.

There, in Birmingham decades ago, his mother, Agnes Carr deShazo, a dental hygienist, had provided furtive dental care to their housekeeper, Mary Rice.

“I saw my mother having to sneak our faithful maid into her office to pull her teeth because Miss Mary didn’t have any money. I saw my mother having to bootleg blood pressure medicine for her,” he said.

“After my mother went into a nursing home and we had to move, Miss Mary could no longer get her medicine. She ended up having a stroke, and died.”

When asked how much his memories of Mary Rice stoke his sustained interest in civil rights history, especially Mississippi’s, he answers quickly: “About 100 percent.”

“Understanding events in Mississippi is central to healing wounds nationwide today,” said deShazo, who worked for two decades at the Medical Center before returning to Alabama last year.

“Mississippi was so desperate to maintain segregation and white supremacy as to tolerate the founding of the White Citizens’ Council (the KKK in suits), and the resurgence of the KKK in the state as the ultraviolent White Knights of the KKK.”

In many ways, the violence that martyred Evers and others helped make possible the career path of another native Alabamian. He also became a physician – after being told he shouldn’t even try.

‘No black physicians’

Brought up in Auburn, Alabama, Dr. Claude Brunson was one of the students who integrated public schools in the early 1970s. As a high school honor student, he let the world know he wanted to be a doctor.

“It was only after I decided to become a physician that I realized there were no black physicians around,” he said.

In Auburn at the time, the only physician was white, and all the TV doctors looked like Marcus Welby, M.D., said Brunson; he wouldn’t see his first black physician until he was old enough to join the Navy as a hospital corpsman.

Brunson first arrived at the Medical Center as a resident, choosing its program based on the reception he got from Dr. David Bruce, chair of the Department of Anesthesiology.

“He spoke to me as if I was just a normal person,” Brunson said.

Still, he was only the second black resident to train in that department. That could explain the attitude of some of the patients. “I walked into their rooms and they thought I was there to connect the TV,” Brunson said.

This was in 1988. Which means that on the night Evers died, Brunson was still about 25 years and more than 300 miles from Jackson, a young boy soaking up the innocence of an Alabama summer.

But what he would accomplish one day in Mississippi would have been less likely minus the activism sparked by the execution of Evers and others.

The fact that Brunson could rise so high in the profession, and at the Medical Center in particular, belies what Dr. James Keeton witnessed there in the 1960s.

‘This isn’t right’

Keeton (’65) was starting his junior year as a medical student the night Medgar Evers was sent, mortally wounded, in a station wagon to the Medical Center emergency room.

A Columbus native, Keeton arrived at the Medical Center as a student in 1961, when African-Americans still weren’t admitted to the School of Medicine.

Keeton, who served as UMMC’s vice chancellor for more than five years, starting in 2009, does not avoid those discussions today. “Evers’ death did have an effect on me,” he said.

It followed him from his days as a student in the School of Medicine to the day he began to lead it and the entire Medical Center, 46 years later.

“People I know say, ‘Stop talking about it, stop talking about slavery,’” Keeton said. “But you can’t forget about history. That’s how you learn.”

The history of the Medical Center is keenly linked to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Because of that, and subsequent, legislation, the walls and symbols of separation in the Medical Center disappeared overnight, as silently as the dying embers of a burning cross in the rain.

“The hero then was Dr. Marston,” Keeton said, referring to the Medical Center director and medical school dean from 1961 to 1965.

Robert Q. Marston’s move to de-segregate prevented a loss of federal funds, probably ensuring the Medical Center’s survival, Keeton said. “If federal funds for research had been lost, a lot of the faculty would have left.”

Some, like Barnes, might have never arrived.

‘The Lord said …’

Driving on a full tank of anger, Helen Barnes had left Mississippi for New York, where she stayed and completed her OB-GYN residency.

By the late 1960’s, she was back home in Mississippi. “My grandmother was ill,” she said.

Previously, starting in 1967, she worked for two years at the Tufts-Delta Health Center in Mound Bayou, co-founded by her friend from Tufts University, Dr. Jack Geiger. She helped black citizens learn how to take the voter registration test, which was designed to ensure their failure.

In October 1969, Barnes joined the Medical Center after Dr. Henry Thiede offered her a job in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. She became the first African-American woman to practice obstetrics in Mississippi and the first black faculty clinician at UMMC.

“I was sort of amazed, but I didn’t run into any racial attitudes in that department,” she said. Patients weren’t necessarily as accepting.

At least twice in her career, whites refused to be treated by her. With her supervisor’s backing, in each case, she treated them anyway.

“The Lord said, ‘If they’re sick, take care of them,’” Barnes said.

For a while, she took care of them at an institution that would have, at one time, forbidden her from studying medicine there. Her medical degree came instead from Howard University – also the alma mater of Robert Smith; that’s where he first met the most famous civil rights icon of all.

‘Crazy to go back there’

Smith, like Barnes, had financed his medical degree through the aid of the Mississippi Medical Education Program, which provided loans to black medical students – as long as they didn’t try to get educated in Mississippi.

Smith, who would later join UMMC as an assistant clinical professor of medicine for a time, served as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s personal physician during James Meredith’s 1966 March Against Fear through Mississippi.

In Canton, Smith supervised medical care for the marchers attacked by the Mississippi Highway Patrol.

By then, Smith had been back, and active, in Mississippi for a few years. Among his works: helping establish 20-odd community health centers across the state. He became a leader of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, offering his services to civil rights activists.

Many people called him the “doctor to the movement.” Others called him “crazy.”

“People used to bully me for being from Mississippi,” Smith said. “It was: ‘You’re crazy to go back there. You’ve been liberated now.’”

Unlike Smith, not all of the state’s black physicians were willing to brave threats to their careers and lives, according to “Out in the Rural: A Mississippi Health Center & Its War on Poverty” by Thomas J. Ward Jr.

Not all of them followed the example of people like Smith and the late Dr. Aaron Shirley, who became UMMC’s first black pediatric resident, in 1965, about a year before Sammie Inez Long enrolled as the Medical Center’s first African-American medical student.

Following desegregation, the “firsts” began to accumulate. They’re accumulating still. And that’s the problem, said one of the “firsts.”

‘Something he earned’

“Claude Brunson gradually worked up to more, and higher, positions,” said Barnes, who did join the AMA’s counterpart: the National Medical Association, which represents African-American physicians and their patients.

“That’s something he earned, whether he was black or white.”

It took him a while to get that far. The first time he ran for a seat on the MSMA board, he lost. When he took the president’s chair, in 2013, he was willing to face whatever the role called for. He does not apologize for making the apology, or for its timing.

“My standing is no less than any other president who would have issued the apology,” Brunson said.

What the MSMA expressed regret for “is not what the association is today or who any of us is,” he said, explaining why the statement was a long time coming. “None of us would have acted that way. So our apology would almost seem like we were guilty.”

Still, the board voted on the statement, and did so near the end of Brunson’s service as president. “Whoever was president would issue it,” he said. Brunson decided it was more important to do it right away, rather than wait for the election of a white president, he said.

“In my mind, the important thing was that we did it. It was being sorry for an action they were not a part of … but you acknowledged that on behalf of your forebears, acknowledged it was wrong, and that’s what we had to get past.”

The MSMA apology came seven years after the AMA issued its own, in 2008 – 40 years after its House of Delegates voted to allow for the expulsion of its affiliates for discrimination. That vote was taken in 1968, five years after Smith and others took their grievances and their protest signs to Atlantic City.

The demonstrations had not ended there.

Because Smith did much, at personal risk, to bring about transformation, the AMA presented, in 2017, its Medal of Valor Award to the man who had picketed it 54 years earlier.

Certainly, Brunson has been a beneficiary of that upheaval – the end of disenfranchisement in organized medicine. Besides being named the first African-American to be selected president, then executive director, of the MSMA, he was also the first black chair of a medical school department at UMMC.

By now, though, “the first” is a phrase ringing evermore hollow. “We are well into this century – and we’re just getting to some of these firsts?” Brunson said.

“It’s something to be celebrated, but when you think about it, it’s also kind of sad.”

‘A place of hope’

The man who, literally, tore down walls at UMMC is the namesake of the Robert Q. Marston Symposium on Race and Medicine.

It drew more than 150 UMMC faculty and community physicians, state health officials and others to the Medical Center in 2014. In a follow-up forum a year later, a name was added to the symposium’s title: “Robert Smith, M.D.”

Organized by deShazo, the conferences explored, among other things, the history of Mississippi’s black physicians.

Its lifeblood was racial reconciliation.

“We have improved greatly in Mississippi,” deShazo said. “At the same time, there are voter suppression efforts. We failed to expand Medicaid. In nearly every indicator of health care, we are last or next-to-last.”

And racial reconciliation is still a work in progress, he said. “You don’t forgive unless everyone admits to what was done. Then you move to forgiveness.”

Barnes, for one, has moved closer to that neighborhood. Awarded the MSMA’s Community Service Award in 2014, she said forgiveness is possible, mostly.

As a young person himself, Keeton had let the movement for inclusion pass him by, he said. Years later, he tried to catch up.

Among other things, he worked with the Mississippi State Department of Health and black physicians, including Dr. Aaron Shirley, on the Mississippi Healthy Linkages Project. One of its goals is to narrow the health-disparities gap for vulnerable patients.

If similar changes are to come, Keeton said, the institution he once led can lead the way.

“It’s like the United Nations here – the mix of races, creeds. We have the opportunity to show the world we are all in this together. Our mission is the right mission: to take care of human beings. Our mission can change the thinking in Mississippi.

“Do I see hope? Hell, I have to see hope. I believe this is a place of hope. Health care may be the one thing that brings us back together.”

For his part, Brunson is trying to bring together the members of the two statewide medical associations.

They, too, have a past to get past – the one with each other, said Brunson, who has served on the board of the predominantly black NMA affiliate, the Mississippi Medical and Surgical Association.

“Black physicians believe there is a place for two medical associations while the predominantly white [MSMA] is still in the process of integrating.”

A priority of the black physicians’ group is access to health care for black patients and the poor – “and that’s good,” Brunson said.

“The MSMA is working on that also, but obviously, it also has a broader focus.” It’s also obvious that both the AMA and MSMA have “come a long way,” he said.

One of the physicians who helped pay for their ticket also, like Keeton, sees hope.

“UMMC now is something we can all be proud of. It has some problems, but I’m proud of the [vice chancellors] who built on its progress,” Smith said.

A sign of that progress: The year the first Marston Symposium convened, UMMC also established the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute for the Elimination of Health Disparities, named for Evers’ widow, a lifelong champion of education and social justice, as was her husband.

The last time Smith saw him was at a meeting at the New Jerusalem Baptist Church in Jackson, which lasted until around midnight. Smith learned later that Evers had been shot in the back after returning home on Guynes Street.

It was one of many civil-rights era murders, but its personal impact on Smith helped change medicine in Mississippi, and beyond.