Rural renewal: Small-town medicine delivers for Indianola doc

This article was originally published in the Summer 2020 edition of Mississippi Medicine, the medical alumni magazine.

DIARY OF A RURAL FAMILY MEDICINE PHYSICIAN

Our life here has totally changed in the last few weeks due to the coronavirus.

We have shifted to seeing patients who need to be seen for sick care and other care in their vehicles. We are triaging patients out front and they are sent to either a sick parking area or well parking area. Our nurses then work up patients car-side and the physician goes out to see the patient.

We have put up tents for inclement weather that patients can drive under, and I’m using my rain boots and rain jacket more than I would like. Patients, however, love this. They see it as such a compassionate, caring way for us to protect them.

Some of them want us to practice medicine like this even when the world returns to normal.

All of our physicians know that at some point we could all possibly have it, but we are trying to limit exposure of sick patients to 2 physicians. We have one physician who is caring for hospitalized COVID patients. She’s my hero, though she is 15 years my junior.

She is trying to protect my family and all of my other partners’ families as long as she can.

On the home front, after working 10+ hours a day, I am homeschooling 4 very active boys. There is definitely a reason I am not a teacher, and I respect them even more than I already did.

I do think I have had more time to enjoy my family instead of running to baseball or running to soccer or some other event. We spend our free time outside and playing card or board games.

We are praying that God protects us and lets us resume life as we once knew

it soon.

– Dr. Katie Patterson, April 2, 2020

THAT (DOC) HOLLYWOOD MOMENT

If she could be a character from a movie, it would be Mary Poppins.

“Mary Poppins would reach into her bag and pull out a solution,” said Dr. Katie Patterson (’03) of Indianola; she, like many rural family medicine doctors, encounters broken lives as well as broken bones, all in the course of a day’s work.

“Sometimes, patients get angry and they say that I don’t understand: ‘You have a car. You have a good place to live. You make a good living.’ And I try to tell them I do understand, and that I do love them.”

For the people who have no one else to talk to, nowhere else to turn, she wishes she could reach into a magic bag of prescriptions and fix everything. And sing a song while she’s doing it.

One of a half-dozen physicians seeing patients at Indianola Family Medical Group, Patterson actually can sing; she can also fix problems, but there aren’t enough songs and spoonsful of sugar to make the medicine go down for every resident who needs help, physically and emotionally, in underserved areas like Sunflower County, a throne-shaped swath of Mississippi that has lost nearly 4,000 of its subjects in the last decade alone.

In the 2020 County Health Rankings, supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Sunflower County, population 25,000-plus, claimed one primary care physician for every 2,930 residents in 2019, compared to one per 1,900 for Mississippi and one per 1,050 for the top U.S. performers. Some counties are worse off.

Only 11 percent of physicians practice in rural communities, reports the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, but one-fifth of the U.S. population lives in them.

Americans living in rural areas, rather than in urban regions, are more likely to die from heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory disease and stroke, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Like her colleagues at the Indianola clinic, Patterson has seen patients with all of those diseases and more come to her for help. And there’s no other place she would rather be. She decided this the first time she saw the Indianola clinic, which was, in fact, the first time she saw Indianola.

“I was a medical student on an externship,” Patterson said. “I delivered my first baby on Day Two. I knew then that this was something I had to do. I was going to be Doc Hollywood.”

Unlike the fictional physician sentenced to community service in a small-town hospital, Patterson did not need a court order to send her where she was needed, or a conspiracy hatched by the townspeople to keep her there.

‘THIS IS WHERE YOU GO’

She knew this was where she belonged long before a pandemic with an 8,000-mile-long arm reached the heart of the Mississippi Delta and tried to pull it out.

She realized something Dr. Wahnee Sherman, executive director of the Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholarship Program, has been telling medical students and residents for years now. If you want to change the world as a physician, this is where you go: rural America, said Sherman, who leads MRPSP’s quest to award scholarships to medical students who pledge to practice small-town, primary care in the state for several years.

Certainly, Patterson helped change the world of JaQuana Haley-Williams, 37, who has lived in the town of Sunflower all her life.

On a morning in early March, Haley-Williams has arrived at the clinic, an eight-mile drive from her home. There’s no physician in Sunflower to take care of her during her pregnancy, and the next-nearest is in Ruleville, about 15 miles north of there, she says.

Haley-Williams was 17 weeks pregnant when she first met Patterson a year earlier at Sunflower County Hospital. She was completely dilated when she lost her baby – her second miscarriage.

Several months later, she came back to Patterson, pregnant again. “She has taken very good care of me. She does exactly what she says she’s going to do,” Haley-Williams said. “I love that about her.”

This time, Patterson was able to refer her patient to a doctor who does cervical cerclage, a stitch to treat cervical weakness, a condition which can cause either a late miscarriage or a preterm birth.

When Haley-Williams arrives at the clinic this day, she is 37 weeks along. She’s having a girl. After examining her, Patterson says she’s having it right now. Patterson sends her patient across the street to the hospital, where she will meet her later, along with her newborn daughter.

“God is divine,” Patterson says.

BABIES AND BRUSSELS SPROUTS

Indianola is one of only two places in Mississippi where a family medicine physician still delivers babies, Sherman said. The other is Waynesboro, courtesy of Dr. Kelvin Sherman (’90), a distant cousin of Wahnee Sherman.

Down the Indianola clinic’s hallway, another patient is waiting for Patterson to deliver him – from pre-diabetes: Stephen Sparks, 48, a United Methodist pastor who has traveled about 140 miles from his home in Olive Branch.

“I’ll drive 2 ½ hours for a good steak,” he says, “so I’ll drive that far for a good doctor.”

Sparks moved to Olive Branch from Indianola eight years ago, but his medically-related allegiance remained in Sunflower County, where Patterson delivered the youngest of his children before the family moved.

“Katie did as good a job as any OB-GYN specialist we ever had,” Sparks said. “She’s good with the babies.

“She’s the best doctor I’ve ever had since my own pediatricians – you have to love them because they give you a sucker. Katie won’t give me a sucker. But she did try to give me a Brussels sprout.”

When Sparks’ examination is complete – with high fives between physician and patient for his A1C reading – Patterson gets on her cell phone and arranges a lunch date between Sparks and her husband David Patterson at the popular Crown Restaurant.

“If you go to eat at any restaurant there, they all know Katie Patterson,” Sherman said. “She’s definitely part of her community and part of the lives of the folks there. That’s the best kind of doctor.”

Sherman has known Patterson for about seven years now, ever since Sherman began directing the MRPSP – which has a strong advocate in the physician from Indianola.

The Indianola clinic is one of the sites in Mississippi where medical school-bound college seniors shadow physicians. “This pretty much started in Indianola because of Dr. Patterson,” Sherman said. “Their encounter there is always the students’ favorite; I believe a big part of that’s because of her.

“They get to see the impact she makes and the enthusiasm she has for her work, as well as the relationships she has with her patients.

“And, because it’s one of the only places where family medicine doctors are doing deliveries, it helps the students understand the breadth of the specialty.”

Patterson and her colleagues deliver about 250 babies each year, Patterson said. They know when to anticipate an onslaught, she said: about nine months after a bout of frosty weather has inflamed a prolonged period of “snuggling,” she said.

It was here, as a medical student, back when future doctors may have had more hands-on training, that Patterson learned how to do a C-section. When you practice medicine here, you’re harking back to the days of doctors’ black bags and house calls.

“We’ve been dinosaurs a long time,” said Patterson, who has made house calls to housebound patients. “Our relationship with our patients, we hope, starts pre-pregnancy and goes on throughout the patients’ lives. And we may gain a grandmother or grandfather along the way.

“We especially get to know the lives the patients live as mothers. If they’re married to a bad dad, we know how that affects their children.”

All in all, Sherman said, “there is no better place in Mississippi for our students to see what rural medicine can be; and, certainly, Dr. Patterson has helped recruit many a student into family medicine.”

And, in a way, the town recruited her – this Texas-born granddaughter of a Greek immigrant who opened a landmark restaurant decades ago in Hattiesburg, the place Patterson claims as her hometown.

A SPOONFUL OF FASOLADA

While Patterson may not have been born and reared a “Delta girl,” said Beth Embry, executive director of the Mississippi Academy of Family Physicians, “she has won that title many times over because of how much she has invested in her town.

“She has started a soccer league, helped build a day care, teaches robotics at the local school and served on many boards and committees of her church, civic league and friends of the library.”

Perhaps because she is, for many of her patients, as entrenched in the community as the Indianola Pecan House and the ghost of B.B. King, they feel comfortable calling her for help in the middle of the night.

“It’s a small town,” Patterson said. “It doesn’t take much to find my cell phone number.”

She got a preview of this doctor-on-demand performance from her own father when she was a little girl.

An “Army brat” born the oldest of three children in College Station, Texas, Patterson was in eighth grade when her family moved to Hattiesburg, where her native-Greek grandfather started the Coney Island restaurant. Her father, Dr. Arthur Fokakis (’79), eats once a month at the eatery the family continues to run.

“My dad, who had been an Air Force doctor, was the only allergist in town,” Patterson said. “So he was on call every day. To be honest, that was kind of a turn-off for me, for a while.”

Katie Fokakis had decided she was going to be a lawyer. “My dad said I could argue anything,” she said. But the example of his own life eventually made a case for the career she finally embraced.

“Once I started visiting his office, everything changed,” she said. She saw how much people depended on him; she saw him take time to hand-write notes for his patients.

That type of personal touch afforded by the practice of medicine was all she needed to know about the profession at that time. Still, she formed a backup plan if she didn’t get to medical school. “I was going to be a caterer,” she said. “I like to cook.”

When she wasn’t throwing together a batch of baklava or fasolada, a Greek version of navy bean soup, she was throwing down on the dance floor. In high school, she received private dance lessons, on top of playing soccer and taking on roles in musical theater – which she does to this day in Indianola.

She really does sing “A Spoonful of Sugar,” or could if she wanted to.

At Hattiesburg High, she was also a serious student who liked to read, especially “Little Women”: the character, Marmee, with her sympathetic ear, is “my mom,” she said. Her name is Mary Virginia Fokakis, but the grandchildren call her Marmee.

Her mom’s life, particularly her struggle with multiple sclerosis, also helped turn Patterson’s career-related thoughts from the courts and to the clinic.

“Some of the greatest things I’ve learned from her are endurance and faith,” Patterson said. All of her folks, particularly her two grandmothers, have shown her how important family is. And how important a doctor can be to family.

She was too young to remember the death of her grandfather, a diabetic and a smoker. But she was not too young to remember watching her father endure the loss of a parent. It was probably her first experience with life-and-death, she said. And so it became her goal to one day help families avoid that burden.

WHO’S ON CALL?

Even so, after finishing her undergraduate degree at the University of Southern Mississippi, Patterson took two years off to figure out if she should cater or doctor for a living. After doing medical billing for a variety of physicians, she was on her way to medical school.

It was a summer externship in Indianola under Dr. Lanny Prichard that lured her back to Indianola Family Medical Group for her third- and fourth-year rotations. She did leave for Corpus Christi, Texas, for her residency, but “I knew I would come back to Mississippi,” she said.

Once she did, she settled in Sunflower County as the first female physician in town to practice family medicine, she said, although there was a female obstetrician before her.

“I was a woman in a very male-dominated society. Having a female physician was a very different take for them. And I am opinionated, which makes it worse.

“But when I got here, the community welcomed me.” In September, she celebrates her 13th anniversary in the town now populated by her four sons – Samuel, 13; Reilly, 10; Nicholas, 9; and John Kastens, 5 – who are learning to cook from their mom.

“It’s a community where we raise our children together and take care of each other,” Patterson said. “I believe a small town is family, regardless of race, religion and circumstances. If your house gets flooded, someone will call and say, ‘I have a place where you can stay.’

“But it’s also a place where, as my children say, you can’t do anything without everyone knowing it. I remember when I came to interview here; I saw this inscription on a napkin: ‘The best thing about being in a small town is, if you don’t know what you’re doing, just ask your neighbor.’

“So, if I don’t know whether I’m on call, I just ask somebody.”

GRIEF AND GRATITUDE

Actually, Patterson is on call for her entire profession, said Embry, the director of the MAFP, for which Patterson is a past president.

“She keeps family medicine strong in Mississippi and I am honored to get to work with her on our issues.” One of those issues, putting more physicians to work in the state, is the task of an MAFP-supported creation, the Office of Mississippi Physician Workforce, whose executive director is Dr. John Mitchell (’86).

“We need more primary care physicians in this state, and the COVID crisis has further emphasized the need for a stronger, broader workforce, especially in rural areas,” said Mitchell, associate professor of medicine at UMMC.

“In Mississippi, about one third of our physicians are 60 years of age or older. And who is most at risk of COVID-19? People who are over age 65. If Mississippi suddenly lost all of our physicians over 65 through retirement or death, we would lose about one-third of our workforce. That’s scary. We need more youth.

“Katie has always said that a rotation she did in Indianola was what enticed her to want to come back there to practice. She is enthusiastic and a great role model for trainees. To all the residents and students that she comes in contact with we hope she can transfer that love and commitment.”

She has transferred that love and commitment to her work on behalf of the OMPW for the Mississippi Delta Family Medicine Residency Program, a new offering that commenced in Greenville this summer.

Embry, for one, believes that, for the Delta, it could be a magnet for physicians: “It’s proven that 60 percent of residents will stay to practice close to the place where they are trained.”

Maybe that’s because they will be embraced in ways they’re more apt to encounter in underserved places – for instance, in a town where patients being triaged inside their cars notice how compassion comes wrapped in a rain jacket and a pair of wet boots: A memorable day, a memorable time, Patterson said.

“But every day is memorable for certain reasons.”

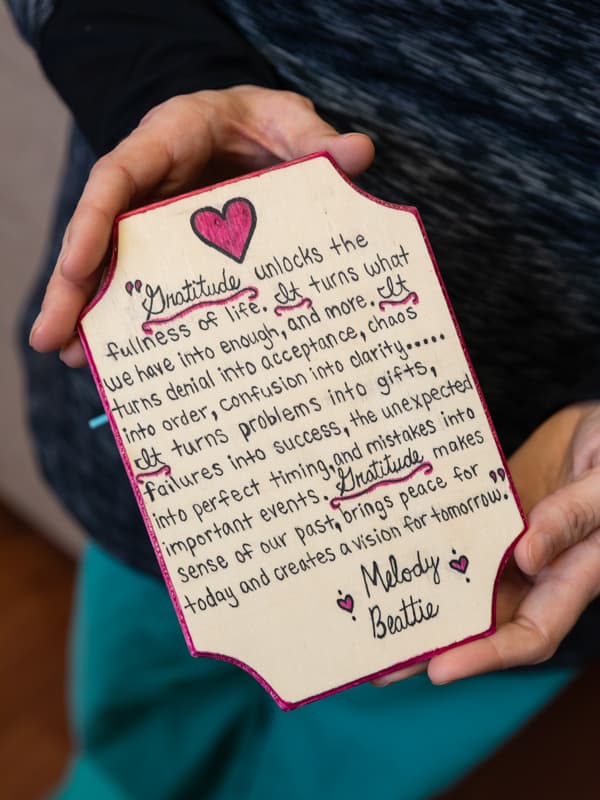

One of those days began with the delivery of a patient’s first son. During the exam, Patterson found no fetal heartbeat. The baby had not been alive for some time.

Two days later, the patient came back. “She brought me a plaque,” Patterson said. It was inscribed with a poem about gratitude.

“She was telling me how grateful she was for my love in a terrible period in her life. It was super sweet of her, especially in her grief.”

That was years ago, sometime before the woman gave birth again – this time to a living son.

The plaque is still on Patterson’s desk, she said. “I’ll never throw it away.”