Trauma training helps rural providers save lives

When someone who’s suffered severe trauma arrives at a rural hospital emergency room, physicians or nurse practitioners on duty don’t have the resources to give them the start-to-finish care they need.

Instead, says the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Dr. Gregory Timberlake, their job is three-fold: Evaluate the patient, keep him alive, and transfer him to an appropriate facility, ideally a trauma center. And, learn how to do that by getting specialized training.

UMMC has been teaching Advanced Trauma Life Support to providers and first responders for 35 years – a record matched by only a few other institutions. Also known as ATLS, the training was developed by the American College of Surgeons for medical providers who manage acute trauma cases.

The goal is to prepare them to stabilize “pretty much any injury that can occur,” said Timberlake, a longtime professor of trauma surgery and critical care. He now serves as professor emeritus of general surgery and leader of UMMC’s ATLS training. Timberlake has been a course instructor since 1981, and was one of the first ATLS instructors trained in the nation.

ATLS evolved from a training system created by a Lincoln, Neb., orthopedic surgeon, Dr. James K. Styner, who was piloting a light aircraft in 1976 when it crashed into a rural Nebraska field. His wife was killed instantly; three of his four children suffered critical injuries.

Styner was horrified to find the nearest hospital closed. Even after someone was called to open it, he saw that the emergency care at such a small regional facility was both lacking and inappropriate. From that came ATLS, a system for saving lives in situations of medical trauma that was adopted in 1980 by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma.

“We are teaching them enough to keep patients alive until they can transfer them to an institution where they have the capability to manage the injury,” Timberlake said. “We focus on the base layers of knowledge that are needed for a physician who sees an injured patient, regardless of what type hospital.”

ATLS is offered at UMMC through the Division of Continuing Health Professional Education. The target audience: Anyone who could care for patients in an emergency setting. “We have people wanting to come to our class for its reputation. We get orthopedic doctors, nurses, urologists. We have medical and pediatric residents who take it,” Timberlake said.

“A lot of folks didn’t do a formal emergency medicine residency, but they work in rural ERs. They particularly need to come. And we have people who might just want to do some ER work.”

Dr. John McCarter, associate professor of emergency medicine, has trained a number of nurse practitioners working at rural emergency rooms who treat trauma patients at their facilities because they have no emergency medicine physician. McCarter also serves as medical director of disaster services for the Mississippi Center for Emergency Services.

In a mock treatment scenario, Dr. John McCarter, associate professor of emergency medicine, talks via live Telemergency video connection with Genie Vaughan, an emergency room nurse practitioner at Franklin County Hospital in Meadville.

McCarter constantly speaks with those nurse practitioners through UMMC’s Telemergency program. Via live videoconferencing, he can observe their patients and provide support. UMMC requires NPs taking part in telemergency to have ATLS training and follow-up refresher courses.

“A trauma case can require intubation, decompression, chest tubes -- intensive things that they don’t do every day. Here, we do that on a weekly basis,” McCarter said. “When I’m watching a patient over the monitor, I can’t grab the scalpel and put the chest tube in. The nurse practitioners need the hands-on skills to stabilize trauma patients and recognize the disease processes.”

About a quarter of those trained at UMMC in ATLS are from the Medical Center, and about half from are other parts of the state. The remaining quarter come from across the nation, in addition to previous students from Belize and Ireland.

They include Genie Vaughan, a nurse practitioner in the emergency rooms of rural Franklin County Hospital in Meadville and Lawrence County Hospital in Monticello. Those hospitals rely on Vaughan and other emergency medicine-trained NPs because they have difficulty attracting emergency medicine physicians.

Although Vaughan sees her share of flu and bronchitis, she also treats serious trauma, heart and stroke cases that, because of her ATLS training, she’s prepared to handle. Vaughan connects through telemergency with emergency medicine physicians at UMMC.

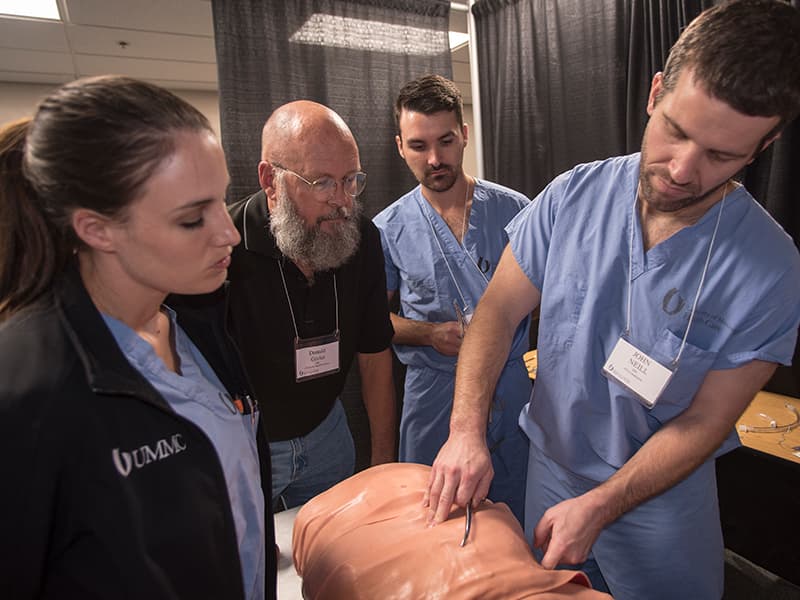

ATLS training, she said, is “a hands-on class, and it’s very detailed and very thorough. The whole goal is to understand and be able to evaluate the situation, determine if it’s life or death, stabilize the patient and get them to the higher level of care they need.”

The basic ATLS course covers two to two-and-a-half full days and includes lectures, skills stations, and written pre- and post-tests. Those taking part are tested on staged scenarios for a patient who has suffered severe trauma. “They must demonstrate their understanding so that they can resuscitate a patient until they can be transferred,” Timberlake said.

They learn to survey a patient using the checklist ABCDE, or airway, breathing, circulation and catastrophic hemorrhage, disability and environment/exposure.

Providers then move to a head- to toe-examination, obtaining when possible a medical history and a rundown of medication. “You need to find out what happened to them,” Timberlake said. “If you’re in a car crash and you’re hit from the left side, when they pull you out, you likely won’t look deformed. But, if the steering wheel collapsed, we need to look very carefully at your chest.

“We teach them how to put in a chest tube,” Timberlake said. “Eighty-five percent of chest injuries require a tube. We teach them how to put a catheter into the lining of the heart, where blood might have accumulated. We have ultrasound here for that, but a small hospital might not have access to it.”

Such procedures “are not something you do every day,” said Vaughan, who is certified in telemergency medicine. “Before I trained, I would not have had that knowledge.”

Mississippi is fortunate in that it has the Mississippi Trauma Care System, a network that specifies regionally where patients with acute trauma will be transferred for a higher level of care. “There are parts of the country where it’s difficult and chaotic to get a transfer,” Timberlake said. “You have to call around and find a hospital that will take them.”

Nurse practitioners in the state’s rural emergency rooms, Vaughan said, “can function and work independently, but we know our limitations. We are greater than an hour from a larger facility. The ATLS training is so important.”

“It makes our relationships flow easier,” McCarter said. “I know we will be able to work together during a trauma because we already practiced that in a classroom setting.”