Decades go by, yet child hunger and poverty endure in the Delta

The same struggles that have stymied Mississippi’s Delta for decades define the total existence of Otibehia Allen, a single parent of five barely able to keep food in her children’s mouths.

Unlike some in Jonestown, a tiny Coahoma County town of 1,200, Allen is fortunate: She has a job. She’s a part-time data entry clerk at the Aaron E. Henry Community Health Center in Clarksdale, 12 miles down the road. Allen doesn’t have a car and pays someone $20 a day to take her to work. Getting to an actual grocery store is just as hard.

“I try, every day,” Allen said after fighting twice to gain her composure and control her tears at Mary Bethel Missionary Baptist, where she stood at the front of the church and told her story.

She’s all but panicked by how her family could be impacted by proposed federal and state legislation that would deeply slash Medicaid funding and, potentially, what little access to health care and other safety-net resources she has.

“If you take these things from us, my children will not survive,” said Allen, 32. “Are you telling me you want me to die? That if you take these things from us, you’re better than us? Our complexions might not be the same, but we all need equal opportunity.”

Hers is the face of poverty and food insecurity that bears a frustrating resemblance to what U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy saw in 1967, at the invitation of a 27-year-old NAACP legal defense attorney who testified before a Senate subcommittee taking a look at programs to fight child poverty.

Come to the Mississippi Delta and see poverty and malnourished children for yourself, the woman who went on to found the Children’s Defense Fund said. Bobby Kennedy said yes.

What he witnessed – emaciated children that didn’t know where their next meal was coming from, wearing ragged clothing, living in shacks – galvanized him to demand federal programs targeting hunger and to address the dearth of government assistance so that children and families living in poverty would receive better care.

Marian Wright Edelman, now executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund, on July 11-12 revisited the historic Delta poverty tour she took 50 years ago with Kennedy. She boarded a chartered bus with an entourage of journalists, lawmakers, health advocates and economic developers for a tour of Glendora in Tallahatchie County, Jonestown in Coahoma County, and Marks in Quitman County.

Also on the bus was a delegation of University of Mississippi Medical Center physicians and nurse leadership. Just like Edelman and health care champions who came before them, they are effecting change in child health outcomes in the Delta by operating safety-net school-based and mobile clinics in the most impoverished communities.

From start to finish, Edelman’s mantra did not change. “This is the most dangerous time we’ve faced,” Edelman said. “I can’t think why a state can turn its back on millions of Medicaid dollars. This is a time that we need to decide not to go backward. We need to go forward.”

In Jonestown, or Glendora, or Marks, it’s easy to see some things haven’t changed much since Bobby Kennedy came around. It’s easy to see why UMMC’s health outreach is making the difference between thousands of children and adults getting primary care or going without.

Overall access to health care is still abysmal, keeping the Delta’s high rates of diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and obesity among the worst in the nation. Employment prospects remain dismal. Schools are dilapidated and receive rock-bottom ratings from the Mississippi Department of Education. Economic development remains a constant struggle.

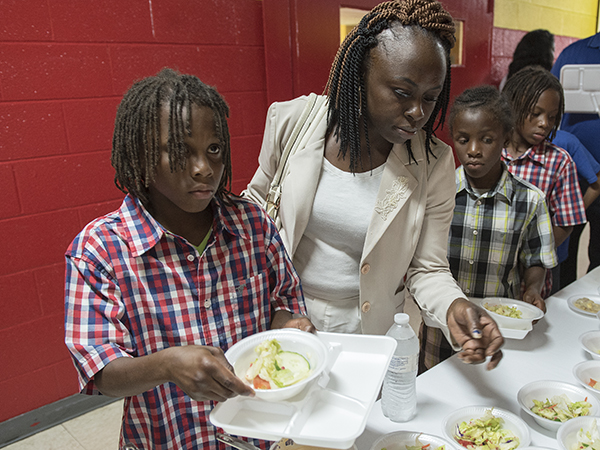

Thousands still live in what’s called a food desert – communities with no grocery store and little or no access to fresh fruits and vegetables. They live with food insecurity, which means they’re unsure where their next meal will come from. Mississippi leads the nation in food insecurity, with 22 percent affected, much of it in the Delta.

But, it’s better than it was in 1967, even though about 34 percent of Mississippi children live in poverty, down from about 50 percent when Kennedy visited. And while gaps in health care abound, the Delta now has a number of community-based clinics. Through its Mercy Delta Express Project, the University of Mississippi School of Nursing created and staffs three in-school clinics and one Head Start clinic in Sharkey County, which has no pediatricians.

UMMC operates primary care clinics in West, Winona and Vaiden, and will open an urgent care clinic in Belzoni this fall. Thanks to UMMC’s Center for Telehealth, Mississippi is a national leader in people connecting to health care providers through their tablets, computers or smartphones. A great majority of those patients are from rural areas.

And the Medical Center’s new School of Population Health is critical not just to the Delta, but to the state as it seeks better insight into the prevention and treatment of diseases by addressing poverty and health disparities that impact whole communities.

Although their future may be in some jeopardy, safety-net programs are in place, including school-based children’s feeding programs; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly food stamps; and the state Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP. About 459,000 Mississippi kids are covered by Medicaid or CHIP.

“There are so many issues that face our kids in schools that aren’t obvious,” Aurelia Jones-Taylor, executive director of the Aaron E. Henry Community Health Services Center in Clarksdale, said during a panel discussion on the tour at Madison-Shannon Palmer High in Marks. “There are nutrition problems. They may not be able to see, and they don’t know they can’t see.”

As Edelman and the tour bus stopped in the three communities, their mayors listed the woes that keep their economy depressed and residents in a cycle of dependency. Even so, there is hope.

“We are six times a food desert because people had to travel 60 miles round-trip to get food,” said Glendora Mayor Johnny Thomas. “But we just recently opened a convenience store.”

Mississippi, Edelman said, “is the hungriest state in the nation, and unhealthy children do not learn. Ask them on the first day of school if they’re enrolled in health care, and if they’re not, help them get it.

“We have extreme poverty in the richest, most powerful country in the world. That’s wrong. It’s time for another campaign to end child poverty in the United States of America.”