Black physicians’ struggle: They ‘risked life and limb’

Published in News Stories on December 22, 2014

The stories of nine African-American physicians who helped mend Mississippi’s ruptured society appear in the November issue of the American Journal of Medicine.

UMMC’s Dr. Richard deShazo, Dr. Robert Smith and Leigh Skipworth, program administrator in the School of Medicine, all of Jackson, are co-authors.

Their article, “Black Physicians and the Struggle for Civil Rights: Lessons from the Mississippi Experience: Part 2: Their Lives and Experiences,” is available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934314004926 and is a companion to “Part 1: The Forces for and Against Change,” published in the October print edition of the journal.

Each part is a framework for UMMC’s Marston Symposium on Race and Medicine: “Can Physicians Heal Themselves?” held in June, and for a follow-up forum tentatively set for the summer of 2015.

deShazo

They’re rooted in one essential aim: “racial reconciliation,” said deShazo, UMMC distinguished professor of medicine, pediatrics and immunology, and UMMC’s former chair of medicine.

“The goal was to figure out how to get black and white physicians together to address the health issues that haven’t been addressed in the state.

“There hadn’t been any attempt at racial reconciliation between us.”

The tension is reflected by the presence of two medical societies, one predominantly white – the American Medical Association and its Mississippi chapter — and another formed by African-Americans: the National Medical Association and its state chapter.

“In Mississippi,” deShazo said, “I have found trust and communication issues among the two physician communities that adversely affect advocacy for improving Mississippi’s last place in health.”

Although the separate organizations are products of Mississippi’s extinct Jim Crow laws, the division has endured as a legacy of the AMA’s refusal to admit blacks to full membership until 1968 – an act of discrimination it did not apologize for until 40 years later.

“The Mississippi State Medical Association (MSMA) had never apologized for the way it had treated black physicians,” deShazo said. “We thought the symposium would be a good way to get to this.”

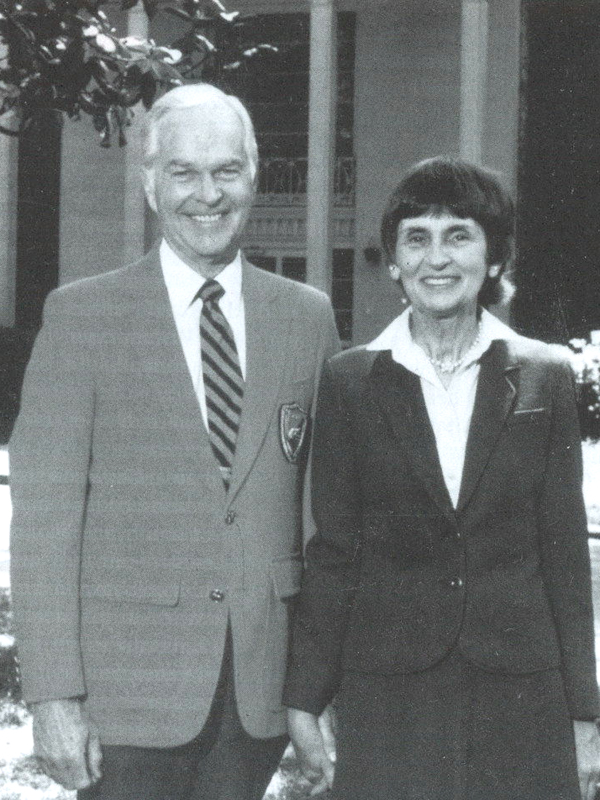

Marston and his wife, Ann

The Marston symposium, named for Dr. Robert Q. Marston, the UMMC vice chancellor who oversaw the integration of the Medical Center in the 1960s, was several years in the making. The idea developed during a meeting among members of the MSMA’s journal who served on its publication committee, including deShazo.

“We were discussing what it would take to meet the health-care needs of the state and its patients,” deShazo said.

“We realized that many of the African-American physicians in the state are not members of the MSMA. We also realized that it is African-American doctors who are mostly taking care of those most affected by disease in the state – the poor.”

For decades, their health has suffered because the careers of their doctors did as well: Black physicians like Smith, in most cases, had been denied admitting privileges to the white-run hospitals and had little or no access to continuing medical education in the past.

The timing of the symposium was tied to the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, a watershed event in the civil rights movement.

Smith at the 2014 Marston Symposium

“I appreciate the Medical Center bringing out some of the awful things that existed in this state that made us Third World,” said Smith, a nationally known advocate for human rights, a practicing physician, a UMMC affiliate faculty member in family medicine, and a student health physician at Tougaloo College.

Smith had picketed the AMA in 1963 for its discriminatory stance. The following year, he gave medical care to civil rights workers during Freedom Summer. “We’ve made some progress, but we need to make more – train more black physicians, get more minority physicians involved in addressing race, poverty, access to care, quality of life,” Smith said.

“We need to fund more training for primary care physicians and make sure they are committed to staying in Mississippi. We need more funding for K-12, which, in my mind will give people the opportunity, through education, to take more responsibility in improving their quality of life and their health.”

Working with the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, a committee chaired by deShazo began organizing the symposium, which would review the history of black physicians and health care for African-Americans in the state.

“In order to do that, I had to do the homework and publish the two articles,” deShazo said. “Mrs. Skipworth provided great help in obtaining historical information.”

As the date for the first symposium loomed, so did a problem.

“We hadn’t been sure we would be able to get the white physicians to come,” deShazo said. “But the black physicians were more reticent than the white ones. They had been treated so poorly over time, they thought they didn’t want to have anything to do with this.”

Engaged in a panel discussion during the 2014 Marston Symposium are (from left) former Governor William Winter, Dr. Claude Brunson, UMMC, Dr. Shirley Donelson, Baptist Medical Center, and Dr. Cameron Guild, UMMC.

For help, deShazo turned to Smith. “He got African-American physicians to come to the symposium,” deShazo said. “We had an incredible turnout: 180 physicians, black and white. It was a great start.”

While Part 1 of “Black Physicians” focuses on the overall battle against segregation, Part 2 spotlights nine Mississippi doctors “who risked life, limb, and personal success to improve the lot of those they served,” as the article states.

At least three have strong ties to UMMC: Dr. Helen Barnes, associate professor emeritus of ob-gyn; Smith; and Dr. Aaron Shirley, UMMC’s first black resident (1965) and founder of the Jackson Medical Mall, who died in November.

“Now that we have sort of washed the laundry and everyone knows what happened, white physicians can better understand why the black physicians felt so alienated,” deShazo said.

“We’re just trying to get everybody to work together.”

In August, reconciliation may have taken another step forward when the MSMA welcomed to its top post Dr. Claude Brunson, the organization’s first African-American president.

The nine physicians:

- Dr. James Anderson (1936- )

- Dr. Helen Barnes (1929- )

- Dr. Clinton Battle (1927-1994)

- Dr. A.B. Britton (1922-2010)

- Dr. Douglas Lavoisier Conner (1920-1998)

- Dr. T.R.M. Howard (1920-1976)

- Dr. Gilbert Mason (1928-1996)

- Dr. Aaron Shirley (1933-2014)

- Dr. Robert Smith (1936- )