Heart device adds years, improves quality of life

What started out as a routine cold for 16-year-old Sierra Garner became far from routine, landing her in a Jackson hospital emergency room almost too sick to move.

“I had a common cold, and afterward I had chest pains,” said Garner, who’s now 29. “Because I was so young, I didn’t feel like it was my heart. I thought it was a chest cold, but I was extremely sick.”

Then over the course of two weeks, she said, “I couldn’t make it up the stairs. I was out of breath. I felt terrible.”

After tests, the news was unexpected, even though Garner has a family heart disease history: She had dilated cardiomyopathy, a disease that causes the heart chambers to thin, stretch and enlarge, making it harder for them to pump blood to the body.

“The doctor (at the ER) said they didn’t have the doctors to treat me. He transferred me to UMMC, and I went to Batson (the children’s hospital) first because I was under 18,” Garner said.

After transitioning to being an adult patient at the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s University Heart, Garner’s heart function continued to decline even with medications. “That’s when we began talking about LVAD and a heart transplant,” she said.

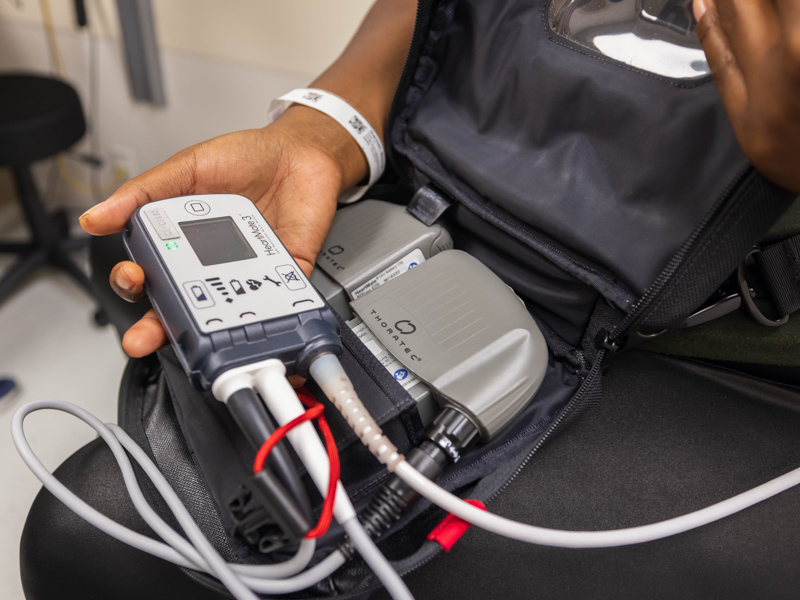

For patients like Garner, the next option can be a ventricular assist device (VAD), a surgically implanted, battery-operated pump that helps take over some or all of the work of the left side of the heart. A left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, is used to stabilize the heart, improving the patient's quality of life.

On Nov. 15, 2022, Garner had LVAD surgery. It was just in time.

“You go into the hospital a few days before the procedure,” Garner said. “I didn’t know how sick I was until they tried to do a heart catheterization. They told me my condition had worsened since the last heart cath.

“Once I recovered from the surgery and the pain, I felt a change,” Garner said. “I’m no longer winded.”

Medical Center surgeons implanted the state’s first LVAD in a patient from Tupelo in 2010, giving her the gift of time and improving her chances for a heart transplant. Today, UMMC remains the only hospital in Mississippi that performs LVAD surgery.

The last decade-plus has produced improvements in technology and treatment, said Dr. Charles Moore, a UMMC cardiologist and section head of Advanced Heart Failure and Transplant Cardiology in the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases.

And with heart disease being the leading cause of death in Mississippi, LVAD can be a game-changer in both quality and quantity of life.

How long a patient uses an LVAD depends on their individual health concerns, “but it truly adds years to people’s lives,” said Dr. Craig Long, a cardiologist and professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases and the LVAD program’s medical director.

Candidates for LVAD “would not be expected to live more than one or two years with such severe heart failure,” Long said. “The death rate for patients hospitalized with heart failure is 75 percent at five years. It’s hard to put a number on it, but the LVAD technology itself can last for 15 to 20 years.”

The LVAD device used at the Medical Center, the HeartMate 3, “is our workhorse device,” Moore said. “It has significant advantages over the HeartMate II.”

“The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is much lower now, and there’s much less chance of having a blood clot form,” Long said. “The LVAD’s controller is smaller and a little easier to interact with.”

The technology still depends on a drive line, a small electrical cable that connects the LVAD pump to an external battery pack. The line exits through the abdomen, connecting to the battery pack worn by the patient like an across-the-body satchel. The battery is recharged about every 12 hours.

The number of patients receiving LVAD varies depending on their degree of illness, but the Medical Center does an average 10 surgeries annually, Moore said. Patients fall into three categories:

- Bridge to transplant – the patient uses an LVAD pending transplant. Sometimes, the patient must first improve their health, such as losing weight.

- Destination therapy – the patient isn’t a candidate for transplant, and will use LVAD for the rest of his life.

- Bridge to decision – it’s unclear whether the patient will bridge to transplant or have destination therapy.

“What we’ve learned is that the length of stay following LVAD surgery and the time to bounce back from surgery depends on how sick the patient is going in,” Moore said. “So, we try to reach patients before they get so sick, and sometimes, you don’t have that luxury.

There’s a knowledge gap, Moore said, among providers out in the state about the opportunities LVAD gives patients and the fact that it can only be done in Mississippi at UMMC. “When we do community education, we try to preach the need for patients to be referred to us earlier than later.”

University Heart’s LVAD program has earned The Joint Commission’s Gold Seal of National Quality Approval for Ventricular Assist Device Destination Therapy, said Susan Allbritton, the Medical Center’s director of accreditation. That certification is renewable every two years, with UMMC receiving a visit earlier this month from a Joint Commission survey team.

Quality of life is much better for Garner and her 9-year-old son Mason.

“I can finally walk around the grocery store without an issue. Before the surgery, there were things I used to enjoy that I couldn’t do, like cooking. I just felt so bad,” the Clinton resident said. “Since the LVAD, I’ve had bursts of energy that I haven’t had in a long time.”

“We have patients who are able to get back to doing lots of the activities they like to do, like playing golf or hunting. Getting the device wet is a problem, so swimming is not in the cards,” Moore said.

University Heart’s LVAD coordinators educate patients and develop a lifelong rapport, said Jamie Kiihnl, who with Katherine Speer is one of the state’s only two LVAD nurse coordinators.

“We teach them how to do dressing changes, how to give themselves a shot if they need to … a long list of things to get them ready,” Kiihnl said of their 30 patients.

Patients can access a 24/7 call line and a support group that meets regularly, Kiihnl said. “We tell them that getting an LVAD is like taking a baby home. You’re nervous about it, even though you know what to do.”

Garner needs to lose about 15 pounds to decrease her body mass index before a transplant. “Around April or May, we’ll discuss it,” she said.

“My dream is to finally be able to work, and my second dream is for me and my baby to get out in the pool again,” Garner said.

Heart failure “is a disease state that needs to be aggressively treated with medications and devices,” Long said. “Not everything is right for every patient, so a work-up is needed to get them on the right therapy.”

For more information on LVAD, or to make a referral or appointment, send an email to lvad@umc.edu or call (601) 984-5078.