UMMC scientists are seq-ing variants to fight COVID-19

As humans develop new ways to manage COVID-19, the virus develops new ways to persist.

We wear masks, and it becomes more transmissible. We come up with better ways to treat the symptoms, and it becomes more virulent. We made vaccines that target the virus’s unique chemical structure, and then the pesky virus goes and changes that structure.

“It’s always a race between the virus trying to survive and the immune system battling the infection,” said Dr. Michael Garrett, professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Studying SARS-CoV-2’s new forms, known as variants, is a critical part of tracking and ending the pandemic and preventing future ones. A multidisciplinary team at UMMC has two contracts to sequence viral genomes in order to determine where, when and which variants are present in Mississippi.

The Mississippi State Department of Health funded UMMC to conduct weekly biosurveillance of virus variants. Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is supporting the Medical Center’s efforts on retrospective study on variants in the state. Together, the projects give UMMC more than $1 million to study COVID-19.

Prior to these projects, Mississippi had little data on virus variants. On April 1 of this year, MSDH had virus genome sequences from about 400 of Mississippi’s 300,000 confirmed COVID-19 infections, said Dr. Ashley Robinson, UMMC professor of microbiology and immunology.

“Even among that small number of sequences, they had found the UK [now known as Alpha] variant, South Africa [Beta] variant and some other variants that we want to keep an eye on,” said Robinson, one of the lead investigators for the study.

MSDH and UMMC are also keeping an eye on Gamma, Delta and Epsilon variants, which emerged in Brazil, India and California, respectively. The CDC classifies all five as a “Variant of Concern,” as there is some evidence that they may be more easily passed from person-to-person, cause more severe infections and be less responsive to monoclonal antibody treatments.

Garrett, the other lead for the studies, said Alpha makes up the majority of variants in Mississippi, but in recent weeks, the Delta variant has rapidly increased in prevalence.

Every time a virus uses human cells to replicate its RNA, it can make mistakes copying the code. If this mistake helps that virus survive, then it gets the chance to replicate. The mistake becomes part of the blueprint for the next generation. Over time, variants can emerge.

Not all variants are “scariants,” – excessively infectious or pathogenic viral strains, Robinson said. When it comes to COVID-19, “The available vaccines are highly effective against these variants, and they help prevent severe infections and hospitalizations.”

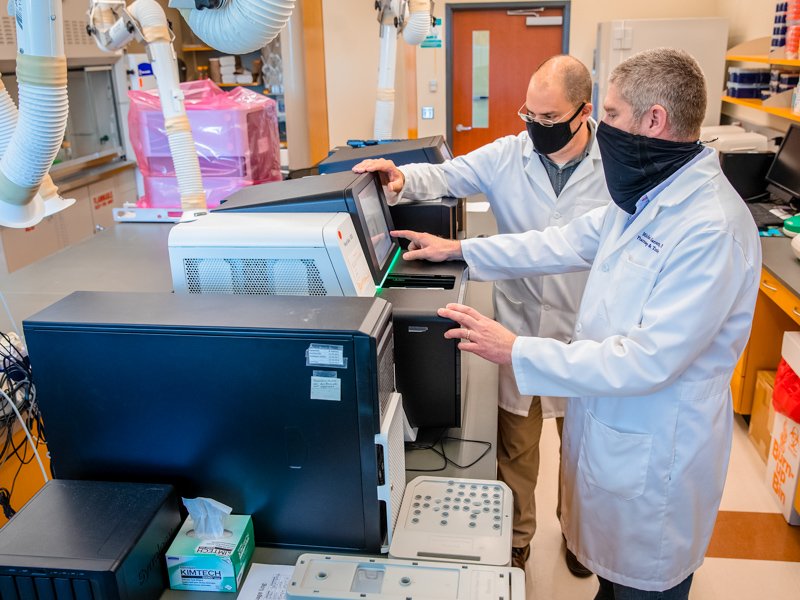

Still, Mississippi has needed this work for a while. Garrett, the director of UMMC’s Molecular and Genomics Core Facility started on pilot projects to test the feasibility of variant sequencing in summer 2020, during the first surge in cases and before variants became widespread.

“In order to get funding for a program, we needed to show we could do it and have results that could help us secure these contracts,” he said.

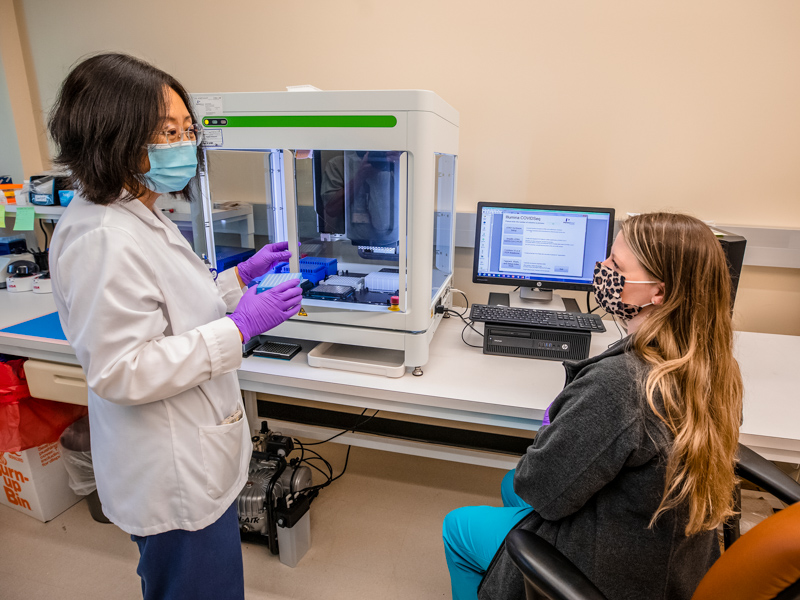

Robinson, associate director for the MGCF, said the final preparations for the work started in February.

“We were coming off these giant peaks in cases and deaths during the winter, and had hundreds of samples to sift through and protocols that needed to be worked out,” he said.

After a series of “fire drills,” Robinson said, UMMC started sequencing the virus genomes for MSDH in March. The team analyzes a subset of positive samples from UMMC’s testing program. The results go to MSDH, which uses the information in its weekly reports and epidemiologic tracking.

“Virus genome sequences are an important tool in identifying COVID-19 cases caused by variants associated with higher mortality or transmissibility,” Garrett said.

The goal is to sequence 3,700 samples from COVID-19 patients in one year. This target may shift based on the success of the most effective tool humans have wielded so far against the pandemic: vaccine-based immunity.

About 32 percent of Mississippians are fully immunized with one of the three vaccines. Infectious diseases experts think that at least 70% percent of the population should be vaccinated against in order to achieve effective herd immunity against COVID-19.

“Increased vaccination rates create an atmosphere with fewer transmissions and fewer mutations,” Garrett said. “As cases diminish because of vaccination efforts, we can look back at which variant were present in Mississippi and how that changed over the course of the pandemic.”

That is the purpose of the CDC project, which will sequence 3,700 genomes from UMMC’s repository.

“Retrospective studies can tell us where the virus strain started, where and when it mutated and how these variants propagate,” Garrett said. “We can look within a given county and can see how quickly infectious variants can come in. Between counties, we can look at how viruses spread between them and what kinds of gatherings contribute to the spread.

“This knowledge also helps inform public health policy. For instance, the data can show if mask mandates work in preventing spread.”

The sequencing work for both the CDC and MSDH contracts is happening in UMMC’s Molecular and Genomics Core Facility. However, faculty and staff from several departments contribute to the projects.

The Department of Pathology transfers COVID-19-positive clinical samples from their clinical testing operations to the research-oriented core facility. Before the samples change labs, UMMC’s Center for Informatics and Analytics removes the identifying information from the patient’s medical record and maintains some demographic information used for analysis. After sequencing, The John D. Bower School of Population Health provides expertise on statistics, bioinformatics and geographic mapping.

“The only way this work gets done is through a multidisciplinary effort,” Garrett said.

Likewise, virus variant analysis is just one piece of the global effort to end the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’m glad to be able to participate in research on what has become the biggest health story in my life time,” Robinson said.