Sim Center drills residents, others on value of communication

For 10 minutes now, the emergency room physicians have been criticized, doubted and rebuffed by a voice erupting from the examination table over which they hover.

These first-year residents, recent medical school graduates, have been given an earful by their handful: “I don’t want to talk to y’all; y’all don’t look very efficient.” “Please don’t touch me.” “How is that safe for me and my baby? Will I have a deformed baby?” “Babies.com says there’s something wrong with that.”

When a resident explains their decisions with: “You’re pregnant,” the response from the table is sharp: “I know I’m pregnant, Sherlock.”

No, the patient isn’t real – her body is that of a mannequin, her personality furnished by the disembodied voice of Catherine Strauss, a University of Mississippi Medical Center researcher; but her words mimic the spirit of a real case that once bedeviled Dr. Jeffrey Orledge, medical director of UMMC’s Simulation and Interprofessional Education Center, where this simulated emergency is being staged.

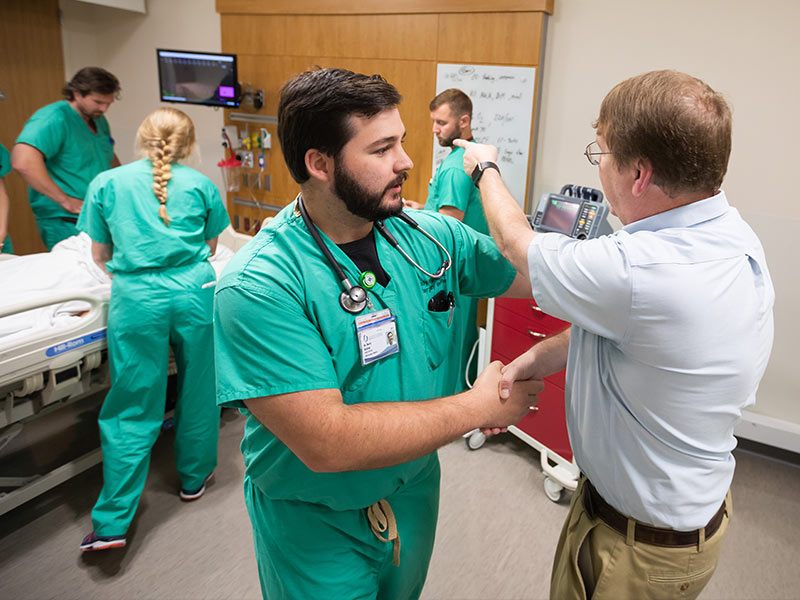

It’s an example of the specialized training available at the SIEC, located on the medical education building’s fourth floor, and designed to not only teach health care professionals how to treat patients medically, but also how to talk to them, and to each other, professionally.

“I’ll ask residents and medical students, ‘What is the most important procedure in medicine?’ And the answer is: communication,” said Dr. John Purvis, associate professor of orthopaedic surgery, whose department’s residents underwent a similar type of teamwork skills training this summer.

“When you look for the root causes of errors made in medicine, lack of communication is right at the top of the list,” Purvis said. “Emphasizing this type of training is pretty important.”

Examples of potentially fateful reticence in the OR, ER, clinic and elsewhere: failure to communicate with a patient’s spouse, neglecting to introduce yourself to other team members, improperly handling checklists and time-outs, ignoring the anesthesia team and marking a surgical site incorrectly – which can lead to an operation on the wrong limb.

In fact, that last error was “planted” in one of the simulated orthopaedic surgery cases, said Joyce Shelby, director of finance and administration for simulation.

“But the residents caught it; they caught everything because they worked together. In real situations, there have been times when, if just one person had spoken up, it would have prevented a whole chain of events.

“It’s about patient safety,” she said. “This training helps stop a lot of preventable errors.”

New and future physicians must detect and remove those errors, often while confronting difficult patients and procedural issues; but this type of training isn’t reserved for them. Included are some students in the School of Pharmacy and the School for Health Related Professions.

Radiology technicians; staff nurses; the Rapid Response Team; the Code Team; AirCare; pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation trainees; and Environmental Services, or housekeeping, staff have, or will, take part as well, as have groups beyond UMMC, such as Mississippi College’s physician assistant studies program.

There is a fee for outside groups, but none for UMMC’s, said Orledge, professor of emergency medicine.

“I look at this as a consulting service,” he said. “This is a resource that can be used by anybody in our system, or outside the system. It’s not only for residents and medical students.” Still, they undergo the bulk of these drills: Orthopaedic surgery residents, for instance, do this every year.

ER residents, during a three-week segment of their summer Boot Camp, tackle artificial heart attacks, diabetic ketoacidosis (a life-threatening risk of diabetes), asthma attacks, seizures, overdoses, trauma, and more, all of which constitute what Orledge calls “the Dirty Dozen”: actually 13 cases most likely to rear up in an emergency room.

“Close to 100 percent of the ER scenarios are based on my personal experience as an ER physician,” Orledge said.

The setting for one is a rural hospital’s emergency department. After the case begins, Orledge transforms into a distraught family member who insults the hospital and questions the treating team, demanding that they transfer the patient. This is the cue for someone to step up: Dr. Dustin Bratton, an ER intern, distracts the antagonist by quizzing him about the patient’s medical history.

“This was an actual case I handled very early in my career,” Orledge says afterward, “and I probably could have done better.”

Orledge often portrays multiple characters, as he does for the case of the boisterous OB-GYN patient, including an inattentive attending physician. Recruited by Orledge, Strauss lurks in a darkened control booth, giving voice, via intercom, to the residents’ pregnant prosecutor, a patient with chest pain and who is as short of patience as she is short of breath.

“My whole body hurts,” she says when asked if her shoulder hurts. “I’m carrying around a bowling ball.”

The practice of medicine is not just about treating medical conditions, Orledge said. “It is also about communication with the family, within the treatment team, with consultants, over the phone. Any breakdown can have consequences.

“As a medical student, you don’t learn how to deal with difficult patients and consulting physicians while at the same time confronting serious medical problems.”

As a medical student, you do learn there are standard procedures, or formulas, for certain cases, said Dr. Erin Walker of Hattiesburg, an ER intern. “The scenarios we faced then were cut-and-dried.

“But for us residents, the simulated situations are more vague; we as clinicians have to tease out what’s wrong. What’s the next step? What medicines do I need? What is unique to this patient? We can talk through a situation with each other and get a better grasp of what should be done.”

As Purvis put it: “The concept of allowing a transitional period after medical school and before jumping in and being real doctors is relatively new. Teaching communication skills, in addition to technical skills, has been around a few years, but teaching these in a SIM Lab is relatively unique.”

Dr. Anna Lerant, professor of anesthesiology and managing director of the SIEC, helped start this particular type of skills and communication training when it was staged originally in the Classroom Wing. Standardized Patients, also known as “patient actors,” are used for some of the scenarios, especially for ultrasound training; but SIEC staffers, such as Orledge, Shelby, Strauss and Patrick Parker, the center’s coordinator, often portray patients as well.

During a pediatrics-related dilemma, Shelby was a mom whose baby had developed sepsis, a life-threatening complication of an infection. “I started crying and screaming,” Shelby said. “So, as a resident, what do you do? Do you focus on the patient or do you focus on the parent? Do you leave the parent in there, or do you take her out of the room?

“A lot of these scenarios involve ethical questions: Is it appropriate to say certain things to the patient? Who do I ask for help? A lot of the residents may not understand that they can ask for help.”

The challenges posed were realistic, said Walker, who graduated from the School of Medicine in May.

“I’m really thankful the Emergency Medicine program had this orientation period for us. I believe everybody could benefit from training like this because, with pretty much any specialty, there will be some patient care on the hospital wards.

“As residents, we had the chance to witness and experience these cases before that first real patient comes through the door. It’s so valuable, because a few months ago we were students, but now we are physicians.”

------------

For more information, or for department heads wishing to request a training session tailored to their learners’ or staff members’ needs, contact Dr. Anna Lerant at 5-7485, alerant@umc.edu; or Joyce Shelby, 5-9082, jshelby@umc.edu.