UMMC becomes the first in Mississippi to offer deep brain stimulation for epilepsy

The University of Mississippi Medical Center is now the first in the state to offer deep brain stimulation as a treatment for epileptic seizures—a breakthrough that brings hope to patients like James Canfield of Moss Point, who has lived with seizures every day of his life.

DBS is a type of neuromodulation technique that uses surgically implanted electrodes to deliver electrical impulses to specific areas of the brain, aiming to reduce symptoms of neurological disorders. For Canfield, it’s a hopeful new beginning after a long and difficult journey with epilepsy.

His seizures began when he was just a few months old.

“We didn’t know what was going on,” his mother, Melissa Parnell, recalls. “He just started this constant blinking one night. It lasted all night. We were so worried.”

After staying up all night with her infant son, Parnell and her husband, David, brought him to his pediatrician, terrified that something was wrong. At first, doctors told her that he would grow out of it. But the non-stop blinking continued.

“I knew it wasn’t normal,” she said. “So, I took him back and they ran an EEG. And it showed constant seizure activity. He was having about 150 seizures a day.”

Canfield was diagnosed with infantile spasms—a rare form of epilepsy that affects infants with sudden, repetitive muscle contractions. He began medications, but they had little effect on his symptoms.Over the years, he tried nearly everything: a ketogenic diet, multiple drug combinations, and even surgery.

As a child, he underwent corpus callosotomy surgery, where the connection between the two sides of the brain is severed to prevent seizures from spreading to the entire brain, and vagus nerve stimulation, a predecessor technology to DBS that channels electrical impulses to the vagus nerve, a small nerve in the neck, rather than the brain itself. While the frequency of his seizures decreased after surgery, they were still having a huge impact on his life.

Eventually, Canfield was diagnosed with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, a rare and severe epilepsy disorder that develops in young children and often leads to lifelong disability. The syndrome is marked by unpredictable, drug-resistant seizures that arise from multiple regions of the brain.

There is very little known about LGS, and it has been linked to multiple causes. Of patients who have been diagnosed with the disorder, 30-35% do not have a known cause.

“Unfortunately, this particular syndrome evolves over time,” said Dr. Omar Chohan, associate professor of neurosurgery, who performed the procedure. “First of all, it’s multifocal, meaning it affects multiple areas in the brain. And it’s not always the same areas that are producing seizures. It might be one area for a few years and then move to a completely different area for a while.”

Not only is the origin of the seizure unpredictable, but the nature of the seizures also changes, ranging from atypical absences, or staring spells, to tonic seizures affecting muscles tone, resulting in full-body muscle weakness or stiffness and rhythmic jerking, which puts individuals at a high safety risk. It often leads to developmental delays and cognitive impairments because of the brain’s constant disruption.

"Patients who fall into this category of unpredictable, drug-resistant epileptic encephalopathy funnel into this final common pathway diagnosed as LGS,” said Dr. Ahmad Mahadeen, assistant professor of neurology. “When they have tried all these treatments and medications and nothing seems to work, the odds of finding an effective treatment become less hopeful.”

Deep brain stimulation was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1997 to treat essential tremors and Parkinson’s disease. It later gained approval as a treatment for dystonia, OCD and, in 2018, epilepsy.

“It’s a very new technology for treatment of epilepsy, and it seems to work for patients with intractable seizures like his,” Chohan said.

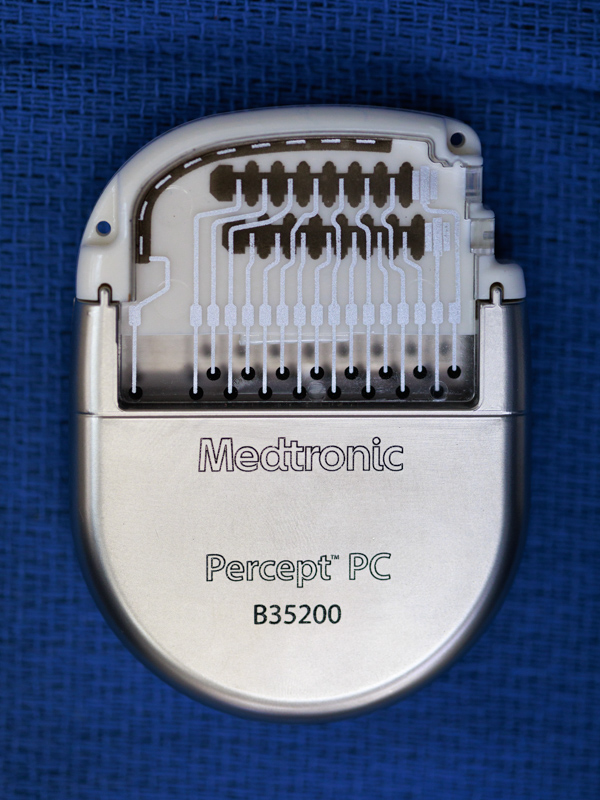

The neurostimulator, about the size of a deck of cards, is implanted under the skin in the chest or abdomen. Thin wires called leads are threaded under the skin, behind the ear and into specific areas of the brain. For epilepsy, those wires target the anterior nucleus of the thalamus—a central relay station of the brain that has connections to the parts of the brain where seizures can begin.

“You can think of the cerebral cortex like the big umbrella. All the information gets condensed into cables and goes through the thalamus,” Chohan explained. “By targeting the thalamus, it doesn’t matter where the seizures are coming from—we're hitting the central relay point.”

An added benefit of DBS is that its effects can improve over time.

“It’s not just suppressing seizures—it’s retraining the brain,” Chohan said. “The results at two years are better than one year, four years better than two. It builds over time.”

It also bypasses a major hurdle faced by many patients with epilepsy before surgery: the need for invasive monitoring to pinpoint the seizures’ origin.

“Typically, patients have to undergo invasive monitoring where we place multiple electrodes throughout the brain, sometimes 20 or 25, and keep the patient in the hospital for multiple days to try to figure out the seizure-onset area,” Chohan said. “Due to the multifocal nature of the seizures in LGS, there is no need to undergo that extra step.”

“This technology offers hope,” said Mahadeen. “We can't promise a cure from epilepsy. We can’t say there will be no more seizures. What we can say is that it has been proven to reduce them over time. And we hope that means a better quality of life—for the patient and the people who care for them.”

So far, Canfield’s mom said, his seizures have already decreased from around eight a day to three.

“It’s still early, but we’re hopeful,” she said. “I don’t want him to be in all this pain anymore. I would love it if he could stop taking some of these medications.”

Parnell, who has three other children, said her son loves being with his siblings, taking walks in his walker, and spending time outside. “I want him to be able to enjoy life.”