Pump gives heart failure patients quality of life, hope for future

It was just eight months ago, Harold Mayberry remembers, that his cardiologists at another Mississippi hospital said there was nothing more they could do.

"They gave me a few days for nature to take its course," said Mayberry, 57, who has coped with congestive heart failure since 2005 and endured the heart-attack deaths of two older brothers and his mother.

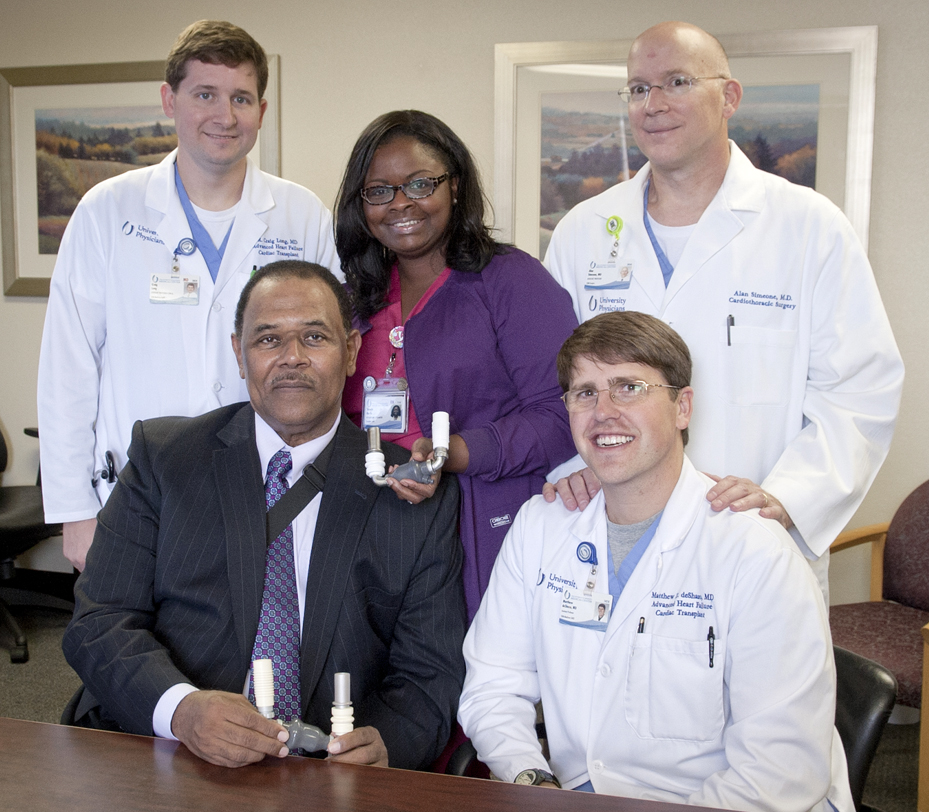

As he neared a two-week hospital stay, Mayberry said, doctors suggested he transfer for a higher level of care to the University of Mississippi Medical Center. There, cardiac surgeon Dr. Alan Simeone is implanting what's known as a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, into the chests of end-stage heart failure patients whose hearts are so weak they can no longer pump blood effectively.

Heart failure cardiologist "Dr. Charles Moore and his team examined me at UMMC, and told me what was going on," said Mayberry, a Jackson resident who for months had been blacking out and struggling just to breathe. "I had my surgery Nov. 13."

Today, he's got his life back and could be a candidate for a heart transplant if he loses weight. "I get on the treadmill. I ride the bike. I can do all kinds of things that I could not do before my LVAD," Mayberry said.

Simeone implanted Mayberry's LVAD, a pump device which takes blood from a patient's bottom left heart chamber and pushes it through to the aorta, which takes oxygen-rich blood to the body.

"We don't want to have to put pumps in people, or to give them a heart transplant," Simeone said. "But when you get to the point where you have end-stage heart failure and you've gotten all the benefits you can from regular therapy, then the LVAD can be your best option to live longer and feel better. We want our patients to have a good quality of life."

It's powered by a pair of batteries that the patient wears; Mayberry said it's like having a computer bag slung across his shoulder. The pump is plugged into a battery unit beside the patient's bed at night. Patients often return to work and resume much of their physical activity. Their two-year survival rate is about 90 percent.

In contrast, most end-stage heart failure patients who don't get an LVAD have very little quality of life. Their average one-year survival with best medical therapy is 30-50 percent.

Medications for patients in end-stage heart failure aren't as effective. Their activities are significantly limited, and they may begin to experience failure of other organs along with swelling of their heart and limbs, Simeone said. "They need to ask the question: Do I need to see someone who only does heart-failure treatment for a living?" Simeone said.

Simeone, a cardiac surgeon with specialized training in LVAD placement and heart transplantation, and two additional heart-failure specialists, Dr. Craig Long and Dr. Matthew deShazo, recently joined Moore at UMMC. "We are glad to be able to offer this therapy to the heart failure patients in Mississippi," Long said.

Long, deShazo and Moore are the state's only fellowship-trained heart failure and transplant cardiologists, Simeone said. "That's a huge asset for Mississippi and the Jackson area," he said. "Unfortunately, a lot of people are being treated for heart failure but are still coming back and forth to the hospital and emergency room due to worsened symptoms."

LVAD implantation is major surgery. The team so far has implanted 20. Thirteen of the recipients are current patients at UMMC, "and we're working up new patients every day," deShazo said.

The team uses the HeartMate II pump, a far cry technologically from those used over the past three decades. Even since 2010, when Tupelo resident Jackie Kirkman became the first UMMC patient to receive the device, the technology continues to advance.

"The LVAD is much smaller, and there are new generations being studied that are even smaller," Long said. They're more easily implanted and easier to remove if a patient receives a new heart.

"They haven't worn out or broken," Simeone said. Mayberry does stomach crunches during therapy; he can barely feel the pump, he said.

Nationally, Simeone said, the longest a patient has lived with a single LVAD is eight years, with some undergoing a heart transplant, and others adjusting to a permanent LVAD, termed "destination therapy."

"There are a limited number of hearts available for transplant, but this pump comes off the shelf," deShazo said.

They caution that patients should consider an LVAD before their heart failure becomes grave. "The most important thing is to get people seen by a heart failure specialist sooner than later so that you can have the best outcome," deShazo said.

Their youngest LVAD patient is in his 20s; the oldest, in his 70s. "You can have a pump implanted when you are reasonably well and spend 7-10 days in the hospital," Simeone said. Patients who are extremely sick could spend two to three weeks in the hospital.

Simeone and the team are frank with patients about possible short-term complications, such as bleeding or infection, and long-term complications including stroke or thrombosis of the pump. “The pump is not perfect. There can be problems, but once those are minimized, the future looks very bright,” he said.

Education, the team says, is key to patients and the community at large discovering that the LVAD can restore quality of life and make possible a plan for continued therapy. They encourage those with questions to email LVAD@umc.edu or call 601-984-5078.

Mayberry has gone from the edge of losing hope to eagerly looking forward to quality time with his church and family.

“I’ve had no significant problems at all,” he said. “My life has really been enhanced.”