Trading punches with Parkinson's: Retired surgeon writes a new legacy with fists and pen

Editor's Note: A version of this story first appeared in the summer 2022 issue of Mississippi Medicine.

There is no downside to faith. – “Parkinson’s First Hero: King David”

No one saw it coming. No one expected it of a man in his seventies, much less of a man in his seventies with Parkinson’s disease.

He jumped. He leapt off the stage.

In mid-air, the arms of Dr. Randy Voyles (’75) rose above his head, like the wings of a bird or an angel. About three feet later, his shoes hit the floor.

It was a November night at the Jackson Country Club; Voyles was among those inducted into the UMMC Medical Alumni Hall of Fame. He was making his acceptance speech and, as he does with any task, he jumped in with both feet.

And landed well.

“I thank UMC for this honor,” he said to an audience whose surprised gasps still hung in the air, “because it really, really will dress up an obituary.”

Everyone laughed. Obituary? Looking at this tall, alert figure gliding across the room in constant motion, brandishing a microphone like a scepter, it didn’t seem possible.

In the cave, I told God about my troubles and asked for mercy …”– “Parkinson’s Boxing, Collections/Reflections”

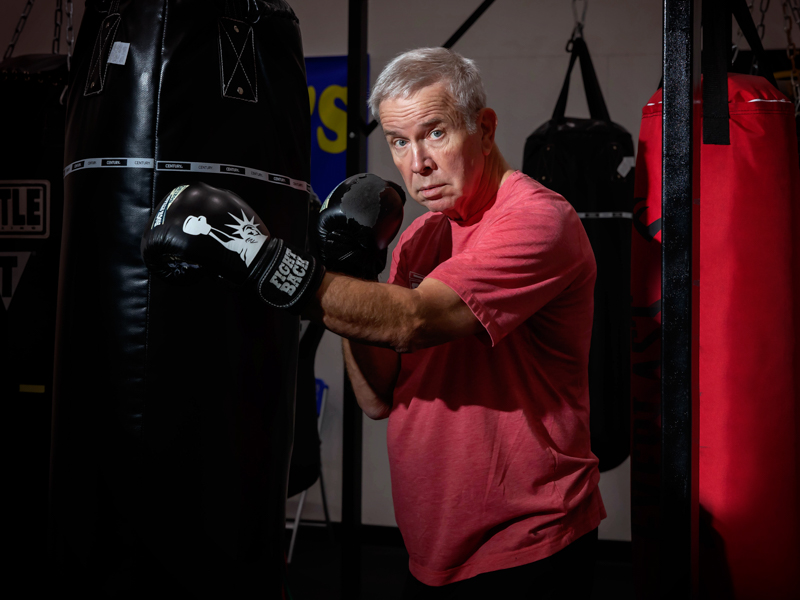

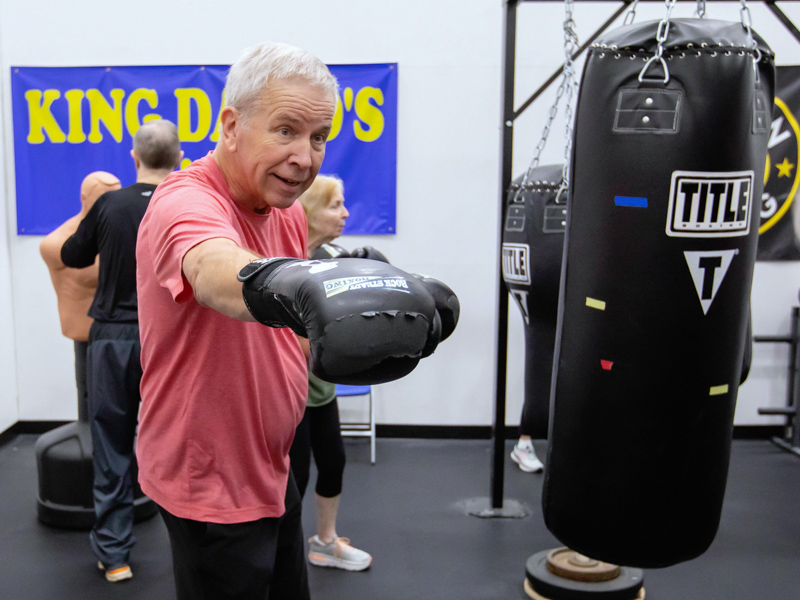

Twice a week he enters King David’s Cave.

He’s one of dozens of committed souls who appear religiously in this workout room inside the Christian Life Center of First Baptist Church in Jackson; there, they fight – literally, with boxing gloves – their common enemy: Parkinson’s disease.

Voyles, a retired Jackson surgeon, was a pioneering, early champion of laparoscopic surgery who operated in theaters as far-flung as Far East. He has written several self-published books, including those about Lorenzo de’ Medici, King David and Adolf Hitler and the disease that bound them together – and to him.

But, inside King David’s Cave, he’s not known as “Randle Voyles, MD” or “Dr. Voyles.” He’s “Randy.”

When it comes to gradually impairing posture and balance, stiffening muscles including those of the face, shuddering hands and fingers and damming the flow of words, Parkinson’s is no respecter of persons.

Striking blows against it is “really entertaining,” says Voyles, who named King David’s Cave.

“Aggressive exercise is the best treatment for delaying progression of Parkinson’s. And it just might help if you ever want to jump off a stage.”

On a Tuesday morning, Voyles and his boxing gloves slip early into the Cave, its walls spattered with Bible verses or inciting language. He accosts a boxing dummy resembling Lee Majors from his “Big Valley” days and punches him in the head – “Kabash!” Like it says on the wall.

This is a session of Rock Steady Boxing, part of a training program for people with Parkinson’s. From his corner, the kabashing rings loudest.

“But you have to exercise every day,” he says. “You can stop exercising when you wake up one day and don’t have Parkinson’s.”

You city folk might not appreciate it, but there is a distinctive crunch when an oncoming car rounds the curve of a recently-graded country road. – “Day Trading with my Hebrew Uncle”

When Randy Voyles was a boy, his dad took him to the railroad yard where he worked.

“It was cold and dark,” Voyles recalls,” and I knew there was something else I needed to be doing.” From his career goals list, the boy struck out “railroad switch operator.” And took one step toward his destiny.

He had no idea he would go into medicine until his freshman year at the University of Mississippi. It was a process of “job elimination,” he says.

Born in Ripley as the second of five children, Voyles grew up three counties westward, in the town of Olive Branch, on 25 acres of corn, cows, pigs and a large garden.

“Everyone in school played football and/or basketball,” he says, “but I admit now that I really did not enjoy tackling. I had an early application of ‘at first, do no harm.’”

He loved the country life, but not farming. In high school, he tested well enough on math and science to earn a “stipend” to study at Ole Miss, where he met a student who would one day run three successful businesses. Her name is Betty Ann, and he married her.

Soon, Voyles switched from engineering studies to pre-med, lured to a future in medicine because of his excellent science test scores. His confidence accompanied him to medical school, where, during summer breaks, surgery claimed his heart and mind.

In the surgical clinic where he did physicals and took histories of new patients, he says, “I was intrigued by the problem-solving done by the thoughtful surgeons and how they gave such personal care to their patients.”

After graduating, he and Betty Ann took their belongings to the University of Louisville for Voyles’ residency. From there, they crossed the Atlantic for his fellowship in hepatobiliary surgery at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School.

“Betty Ann never complained about the constraints imposed by my surgical career,” he says, “even to the point of living in London when we had two toddlers, one and three years of age.”

For the next three decades, as an associate in a surgical clinic and as a clinical associate professor of surgery at UMMC, he forged a headline-making career, his work continuing to gain acclaim even as his body began losing ground.

What’s wrong with me? Am I just overly tired? Am I just getting older?–“Parkinson’s First Hero: King David”

For years, he had been losing his sense of smell: a “gift of God,” he joked, considering the odors in the OR. Next, his handwriting suffered.

Voyles had made his name with his hands. They were good hands to be in if you were a medical student, as the future Dr. Barry Berch (’01) discovered.

“From day one, my goal was to be Dr. Voyles,” says Berch, professor of general pediatric surgery at UMMC.

“He was really into the art of using electrical current. We used it every day to coagulate vessels. A device that every surgeon uses is the Bovie device. The principle of electrical surgery was something he was a genius at – how to use electricity to avoid injuring patients.”

Beyond that, Berch says, “Voyles was like a second father to me. He taught me to sew, to tie knots. He helped me get a surgical residency at Vanderbilt.”

As a student, Berch collected data for Voyles on gall bladder surgery patients. “Back then, most always had to stay in the hospital,” Berch says.

“Dr. Voyles wanted to find out which were suitable for surgery as outpatients. We published a paper on this; it could save the patients lots of money.”

Laparoscopic surgery was the key. Voyles was only the second surgeon in Mississippi to perform a laparoscopic gall bladder removal. He started practicing laparoscopy when he was 40 – “young enough to have the background to do something new, but not too old to do it,” he says.

“I had a background in math and science and I was recognized as the guy who did the complicated bile duct stuff.”

Before this system, cuts on a patient’s belly had to be six to 12 inches long. Slender, equipped with a tiny video camera tipped with a light, the laparoscope meant less cutting and quicker recovery.

Voyles performed about 6,000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, said Jackson surgeon Dr. Jason Murphy (‘03), introducing Voyles at the Hall of Fame dinner last fall.

“Dr. Voyles projected humanism in medicine,” Murphy said then. “He was constantly loved and just a true joy. … His patients loved him.”

In the early 1980’s, Voyles saw a patient with jaundice and a lesion of the bile duct that looked like cancer. He told this mother of three he could not cure her with a resection.

“She gave me the most peaceful smile,” he recalls. “She said, ‘Don’t worry, someone greater than you and me is taking care of me.’”

As it turned out, she had a disease which caused obstruction to the bile ducts. She needed a liver transplant; back then, recipients were much less likely to survive. Voyles and his team were able to buy her time with less drastic surgery.

“Seven years later, when advances meant better outcomes, she had a successful liver transplant,” he says. “She displayed the greatest example of faith in my career.”

He would need that example years later as his own ailments set in – the loss of his sense of smell, the bad handwriting, foot drop. “I finished every day totally exhausted,” he says.

“I didn’t operate as quickly anymore and my movements weren’t as automatic.”

The year was 2012. He was in his 60’s; maybe he was just aging, he thought. He and Betty Ann took long walks and talked about it, and he knew, whatever it was, she would be with him.

One day at work, one of his colleagues saw him walking oddly and asked him if something was wrong with his foot. This led to a DaTscan; confirmation: Parkinson’s.

“The next week, I retired from doing major surgery,” Voyles says. “And I didn’t go on call any more. Because anything can happen when you’re on call. I couldn’t fathom the idea of hurting somebody.” The hardest part, he says, was telling his two sons.

Soon, he realized he had to retire completely. “I knew that there was no amber light for a surgeon with Parkinson’s disease and it would be wrong in my mind to put patients at risk,” he says.

Eventually, he found King David’s Cave, and a renewed sense of faith. Punches and prayers.

He was writing a new chapter, he says. Dozens of them.

… [O]ur New Covenant records that suffering produces perseverance; and perseverance produces character; and character, hope.

Goliath’s slayer was his first subject. Voyles embraced him as a model for his own life, finding clues that King David may have had Parkinson’s. He, too, was forced into retirement.

“But he did not give up,” Voyles says. “The point is you can find something else to do.” The ancient ruler of the Israelites traded his sword for psalms. He wrote. So has Voyles. About King David. About other historical figures who showed signs of Parkinson’s.

With his friends from King David’s Cave, Voyles co-wrote “Parkinson’s Boxing.” His best friend became his editor: Betty Ann.

“But I don’t think I’ve paid for the ink it took to write those books,” Voyles says. “I believe I made $36 last year. You’re not recognized as a writer until you’re dead.”

It doesn’t matter. “Writing gives a sense of purpose and offers a legacy for future generations,” he says. “I want to leave something for my great-grandchildren.”

The last page of “Midnight in Florence” carries only two sentences. The second is a prayer: “Will somebody read this in fifty years?”

The first is a jab: “Any proceeds from the sale of this book or content will be forwarded to a special fund for retired surgeons with Parkinson’s disease.”

Kabash!

BOOKS BY C. RANDLE VOYLES, MD

- “Parkinson’s First Hero: King David”

- “Midnight in Florence: Splattered by Inferno, Sprinkled by Faulkner

- “Parkinson’s Man of Evil: Adolf Hitler”

- “Parkinson’s Boxing: Collections/Reflections (with Mike Brister, Sheri Carter, Jimmy Underwood)

- “Day Trading with My Hebrew Uncle: A Mostly True Novella about Person Finance”