Diversity Champions' mastery projects spur institutional change

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2021 issue of Synergy, the annual magazine for the Office of Diversity and Inclusion.

As admissions chair in the School of Health Related Professions’ Doctor of Health Administration Program at the UMMC, Dr. Elizabeth G. Franklin has long perceived how the cohorts of D.H.A. students from diverse health care backgrounds, different parts of the U.S. and with varied educational, ethnic, racial and socioeconomic backgrounds yield the strongest, most successful graduates.

“These diverse groups also report higher learner satisfaction,” said Franklin, an associate professor of health administration in SHRP. “We seek to develop cohorts that are a combination of health care leaders in our state, as well as from other areas of our country, that represent a variety of backgrounds, beliefs, ethnicity and gender.”

She understood the importance of unconscious bias with regard to hiring employees and also selecting students for a particular program of study, but she wanted to know more, and as importantly, she wanted to apply what she had learned.“Knowing how this standard has worked for us in the D.H.A program, we wanted to dive deeper into why this phenomenon exists and what we can do to avoid any type of unconscious bias that may taint our admissions process and weaken our student cohorts.”

— — —

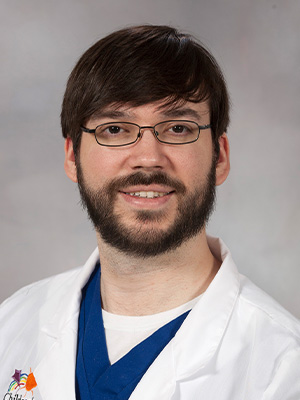

During a quarterly support meeting on 2C, a floor in the Children’s of Mississippi Blair E. Batson Tower, Dr. Charles C. Paine, division chief of palliative medicine, discussed with his staff the profound impact their patients have had on them as pediatric caregivers and their shared desire to provide further benefits to their patients, both physically and emotionally.

“We realized, especially in discussing opportunities for better understanding and care, that there is often a gap in others fully comprehending what children and families with disabilities face on a daily basis,” Paine said. “As with many individualities and identities, it is so difficult to really understand something unless you have lived it.”

Working with Karen Golden, a 2C nurse and mother of a specialneeds child, to develop modules that inform competent, compassionate care for families in the Children’s of Mississippi Complex Care Unit and on 2C, Paine wanted to expand the effort to other units and departments at UMMC.

— — —

“Graduates” of the Diversity and Inclusion Champion Professional Development and Certificate Program, a comprehensive online educational program for UMMC employees on topics related to diversity, inclusion and equity that impact the workplace, research and clinical settings, Franklin and Payne were well equipped with the knowledge and skills to professionally and ethically work in complex environments with diverse employees, patients and clients.

But the catalyst that spurred them to achieve their stated goals of influencing change within the Medical Center was a new mastery-level credential just recently added to the program, “Diversity and Inclusion Project Implementation.”

Established by Dr. Juanyce D. Taylor, UMMC chief diversity and inclusion officer, and administered by Shirley Pandolfi, cultural competency and education manager in the UMMC Office of Diversity and Inclusion, the mastery credential requires the implementation of a new workplace application, practice or initiative within the institution. Successful participants receive a mastery level digital badge, the Diversity and Inclusion Champion pin, a Certificate of Successful Completion of the program, and the satisfaction of knowing their efforts have provided great cultural and societal benefit to the Medical Center.

Pandolfi said the Champion program offers many benefits, such as online learning opportunities; consultations with institutional leaders and subject matter experts; and tools to support job functions. Attendees discover how to build and sustain a more inclusive climate while learning advanced concepts essential

to unconscious bias, cultural competency, skills building and creating inclusive workplace and learning environments.

“Mississippi is more diverse than people realize,” Pandolfi said. “Every individual at UMMC can do something to make our learning, clinical or workplace environment better. Each individual in their own office can make a difference, can advance diversity and inclusion and can help the university bring about cultural change.

“When we are able to be respectful of each other’s differences, it benefits everybody.”

The Champion program consists of 10 levels, each a self-paced online module that provides foundational and advanced concepts essential to skill-building, cultural competency and creating an inclusive workplace and learning environment. Several disciplines have approved the program curriculum for continuing education credit, and after completing each level, participants receive a digital credential.

The program’s levels consist of the following topics:

Level 1: Unconscious Bias in the Workplace

This module describes the natural presence of unconscious bias in the way the human brain receives and interprets information.

Level 2: Unconscious Bias in Health Care

This module identifies behaviors that communicate bias in a provider-patient relationship that impact the provision of quality health care services.

Level 3: Unconscious Bias in the Clinical and Learning Environment

This module describes how unconscious bias is manifested in clinical and learning environments, micro-aggressions and strategies to mitigate the impact of unconscious bias.

Level 4: Unconscious Bias in Recruitment, Selection and Performance Reviews

This module describes how unconscious bias influences the objectivity of evaluating candidates for positions and during the performance review process.

Level 5: Provider Bias and Dealing with Patient Requests

This module demonstrates unconscious bias when dealing with patient requests based on race, gender, faith, cultural backgrounds and other social constructs, and analyzes the clinical environment in the patient-provider relationship.

Level 6: Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in the Electronic Health Record

This module explains stigma and illustrates how to communicate effectively with patients from the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community when providing health care services.

Level 7: A Deeper Look into Employee Discrimination and Harassment

This module provides the tools and skills to interpret and evaluate harassment and all forms of discrimination in the workplace.

Level 8: Responsiveness to Linguistic, Identity and Cultural Needs

This module explains how to reduce disparities and identify access points to public and community services that are culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Level 9: Leadership, Influencing and Communicating Change

This module provides the knowledge to apply new skills to effectively influence and communicate cultural change.

Level 10: Diversity and Inclusion Management, Metrics and Accountability

This module provides qualitative and quantitative metrics for measuring the progress towards diversity goals and accountability to formulate and implement strategies within the organization.

At the conclusion of Level 10, successful candidates take part in a graduation ceremony, receive a lapel pin and certificate, and are recognized during the ODI’s The Pillars awards ceremony in January. They are also encouraged to put their newfound skills into practice at UMMC by submitting a mastery level proposal for a new initiative, practice or project to advance diversity and inclusion at UMMC.

“After the proposal is accepted, participants have to complete two reports - a progress report and a final report - which are shared with institutional leadership at the end of the year,” Pandolfi said.

The Champion program’s first cohort had 72 participants in 2019; of those, eight went on to submit mastery level projects. Of the Champion program’s 62 second cohort participants in 2020, 27 continued working on mastery level projects.

Pandolfi said the benefits of such a dramatic increase in mastery level participation are illustrated by the sheer diversity of the projects submitted.

“We have projects ranging from institutional policy revisions to things people can change in their individual workplaces,” she said. “All of these people are creating change at the Medical Center, creating something special with the people they work with, from welcoming patients in the hospital to teaching students in the schools.

“Some members of the second cohort are using a team approach to their projects. Several members of one office decided to put an initiative together. We are very excited about that, because it’s beneficial to programs and departments when team members get together to have a meaningful discussion about how they can implement change within their department.”

— — —

Paine, a member of the second cohort, initiated just such a team approach with his mastery level project, “Competent and Compassionate Care for Families with Disabled Children.“ Regarding patients and their families, his team members from the School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatric Palliative Medicine - including Shannon Brown, nurse care coordinator; Beaty Hill, inpatient nurse; Latanya Lee, respiratory therapist and ventilator specialist; Annice Little, social worker; Dr. Elizabeth R. Paine, associate professor of medicine; Regina Qadan, nurse practitioner; and Alyssa Sims, respiratory therapist and ventilator specialist - are searching for an optimum strategy “to listen actively, ask respectful and compassionate questions and enter into the lifelong work of walking together with others who are unique from you.”

“This project seeks to provide a ‘walking path’ through these steps with the hopeful result of more competent and compassionate care for children and families living with disability,” Paine said. “Our conversations with staff have resulted in an awareness that there are often disconnects between families and staff surrounding the hospital care of these kids. Families bring their children here and staff serve at UMMC, both because they care and want what is best for these children.

“The stress of illness and the hard work of caring, however, can often cause high emotions on both sides, which can then translate to opportunities for either misunderstanding or active listening and advocacy. We wish to instill the latter through modules which will allow staff at UMMC to ‘walk a mile in another’s shoes.’”

He said the plan is to implement an experiential teaching and learning project which will pair lived experiences from families of disabled children with current and future caregivers and heath care staff to increase communication and understanding between UMMC’s Complex Care Team and 2 Children’s staff and the families that are raising children who have a permanent disability.

“The long-term goals are to develop learning modules that each new staff member on either of these teams must complete in order to more competently and compassionately care for children and families touched by disability,” he said. “We have begun to implement our project through working with Karen and others on 2C to develop these modules for all new staff serving on the unit.”

Paine said initial impressions have been universally positive, and he would like to develop and spread the project further at the institution once his team can demonstrate its success to UMMC leaders.

“Success would be a more open and honest sharing of ideas and concerns between families and staff members,” he said, “as well as having staff more empathic and understanding of the children and families we serve.”

Pandolfi said Paine’s mastery level proposal was the first at UMMC to address children with disabilities.

“That’s the first thing that caught our attention,” she said. “When we talk about diversity and inclusion, appropriate communication plays a big role in an institution’s ability to provide competent, compassionate care. We have seen that sometimes, your culture can affect your views and miscommunication between health care providers and patient families can happen.

“Dr. Paine’s team is trying to add these cultural competency elements to their staff so communication can be more effective between families, health care staff and caregivers.”

— — —

Enhanced communication in the clinical setting is not the only byproduct of a strong commitment to diversity and inclusion. For Franklin, a member of the Champion program’s first cohort, those underlying principles can also fortify academia.

“We often tell our students that they will learn more from each other than from us,” she said. “When we learn about patient safety processes at Oschner, leadership opportunities in the VA system in Tennessee, patient relations at Mayo, quality improvement projects at the UCSF or research protocols in a Native American population, we have a deeper appreciation for the possibilities in Mississippi.”

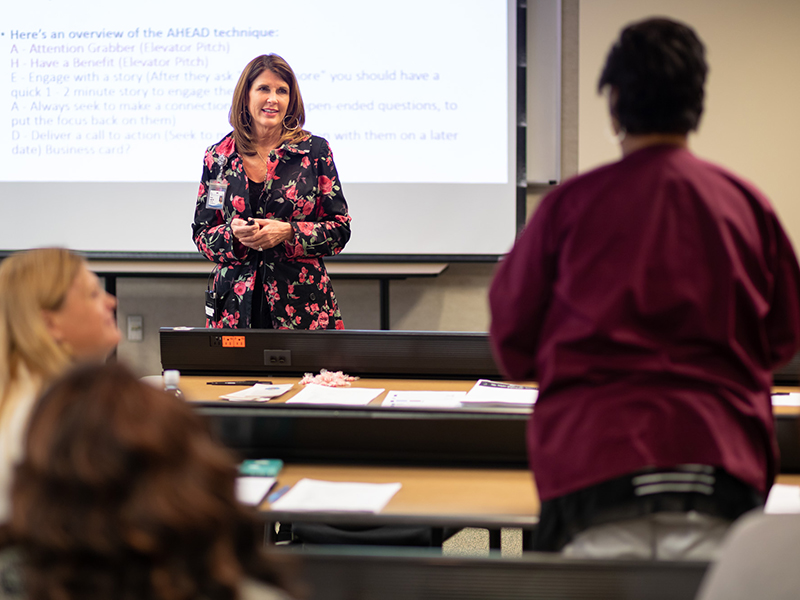

Her mastery level project, “Awareness and Avoidance of Unconscious Bias in the Admissions Process,” shared the research findings and evidence-based information presented by the ODI with the D.H.A. admissions committee and the admissions chairs and co-chairs of the six other academic programs in the School of Health Related Professions, which included Health Informatics and Information Management, Health Sciences, Medical Laboratory Science, Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy and Radiologic Sciences.

With the support of Dr. Angela Burrell, DHA department chair, and Dr. Jessica Bailey, dean of SHRP, Franklin said, “it was important to share the information we had learned with the rest of the school so that their admissions chairs and committees might be aware of and avoid unconscious bias as they recruit and admit students. So we reached out to the ODI for help in providing a speaker for a professional development for all our admission chairs and co-chairs in preparation for the admissions cycle last year.

“The afternoon-long session was a lively, interactive learning opportunity in which we were allowed the freedom to discuss our experiences.”

The SHRP admissions personnel discussed the definition and origin of unconscious bias, the most common types of unconscious bias that occur and how chairs and committees could minimize bias in the recruiting and admissions process.

“The admissions chairs and co-chairs that I have met with since this session have expressed their appreciation for this information and confirmed that, while we all have biases due to basically how our brain works and how it processes our previous experiences, we now have tools for combatting these as we recruit and admit the health professions students that will build the strongest classes each year in all our programs,” she said.

Franklin doesn’t just want to increase awareness of unconscious bias among SHRP admissionsstaff; Pandolfi said she would like to engage prospective students as well.

“When we’re talking about student diversity and inclusion, Dr. Franklin is a good example,” Pandolfi said. “Her project enhances the admissions process regarding inclusion. When applying to the D.H.A. program, applicants have to answer an interview question regarding diversity and inclusion - such as what would you do in this scenario, or what do you think about this topic?”

— — —

Writing a proposal for an impactful mastery level project likeFranklin and Paine’s is one thing; gaining approval from departmentalor school leaders to implement it can be another.

“We read all the projects, initiatives and ideas submitted for the mastery level projects, then we give them our feedback and, even if they don’t have buy-in from their supervisors to support the initiative, we’re able to say how it should be conducted,” Pandolfi said. “Then after one month, we want to know what’s going on with their project - how they are moving forward. In December, we send out a final report that I shared with leadership so they know different people are working to advance diversity and inclusion here in Mississippi.

“They are putting in six months of training and making the effort to work collaboratively on these initiatives. We want to spread the word about these initiatives and how they are moving forward. We want to make them proud of what they are doing to bring about a more inclusive culture at UMMC.”

For their part, Franklin and Paine both regard the Champion program in general - and the mastery level project in particular - as vital agents of change at the Medical Center.

“Dr. Taylor’s team is so important to UMMC because they help bring to mind, for the whole UMMC family, the importance of nurturing a climate of respect and inclusion in all our mission areas,” Franklin said. “They remind us that we can foster excellence in our individual areas by including all points of view and building strength because of - not in spite of - our differences.

“I would encourage all UMMC faculty and staff to participate in the Champion program, and if there is a phase of the certificate program that particularly interests someone, moving ahead to the mastery level is a great way to pilot or implement a diversity initiative in their area. To move beyond the educational content and apply this knowledge in one’s unique area, school or department is a worthwhile endeavor.”

Paine described the Champion program as both “challenging” and “inspirational.”

“(It) was highly recommended by our chair, Dr. Mary Taylor, as a wonderful opportunity for trainees, providers and staff to appreciate the differences in person and perspective that inform our everyday work and interaction here at Children’s of Mississippi,” he said. “Through this self-inquiry and the resulting open and honest discussions surrounding the learning modules, we have been able to grow as a team and provide better care for our patients and colleagues.

“The master level project gives us the opportunity to be advocates in the skills that we learned from the ODI program modules and go ‘where the rubber meets the road’ in order to work towards a more just and more equitable health care system for our patients and families.

“It has made us take a hard look in the mirror individually, and it has made us a more informed and active part of a diverse workforce and community. Most importantly, it has empowered us to come together, to have open and honest conversations and move forward as a team to make the Medical Center a better, more equitable health care resource for families and children living with disability.”