Clinical Investigation program trains doctors for research

One of the SGSHS’s newest degree programs is sending clinicians back to class.

The Master of Science in Clinical Investigation, or MSCI, enrolled its first class in 2016. The two-year, part-time degree program trains professionals in the skills needed to become successful clinical researchers.

Mississippi has a health care provider shortage across disciplines, but it also lacks clinical expertise.

“One of our goals is to develop clinicians who can train others in the future,” said Dr. Betty Herrington, professor of pediatrics and founding program director.

Dr. Richard Summers, associate vice chancellor for research, said the degree program helps fill an important training gap.

“There’s a misconception that by finishing medical school you become a scientist,” Summers said. “Science is a methodology; our goal is to train clinicians in these methods.”

The degree program is designed for clinical professionals with terminal degrees, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists and dentists. Students select a track – clinical trials, population/ outcomes research or translational human studies – and a mentoring committee based on the professional background and interests.

Through coursework and mentorship, the graduates will learn to conduct independent and collaborative clinical studies in their areas of expertise. The program’s capstone project is a submitted extramural funding proposal.

Herrington originally expected to enroll two to four students in the first class, due to size limitations and availability of mentors. Instead, there are seven, a testament to the program’s popularity. Meet three of the clinician-scientists from the inaugural class and learn why they’re in the program:

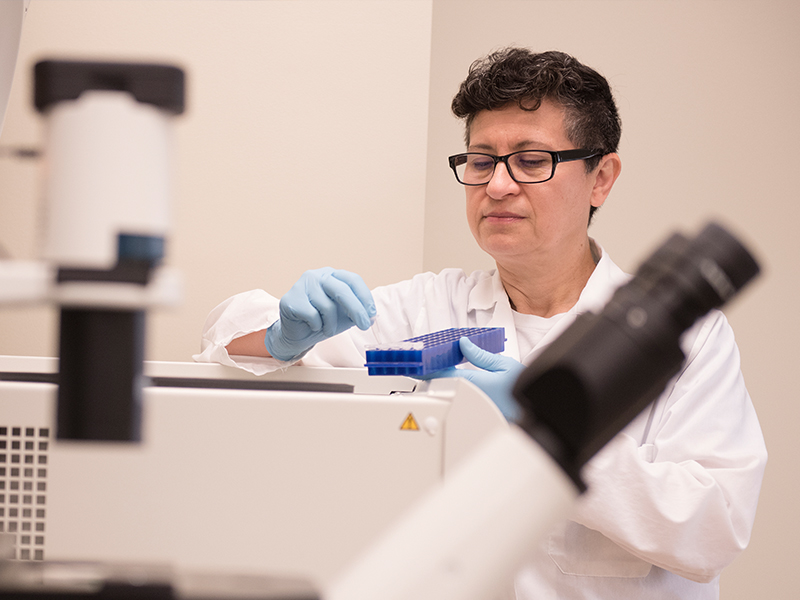

Dr. Norma Ojeda, associate professor of pediatrics-neonatology

As a hematologist-oncologist in Paraguay, Ojeda said she often felt “one step behind” the diseases she was treating.

She would ask: How can I help more people? How can I prevent diseases? Can we find new ways to diagnose these conditions?

“I realized the answers to all of my questions were tied to one common word: research,” she said.

So, to research she went: Ojeda joined UMMC as a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics, where she studied intra-uterine growth restriction fetal programming with Dr. Barbara Alexander.

Ojeda has conducted basic science research for several years and is currently associate director of research for UMMC’s neonatal fellowship program. Even with this experience, she said the MSCI program is the best way for her to advance her own skills.

“It is difficult to receive complete training after finishing medical school,” she said.

Her research proposal project is to study factors associated with breastfeeding behaviors in a group of new mothers at UMMC.

“We have extensive proof that it has benefits for the mother and baby,” Ojeda said. However, Mississippi has one of the lowest breastfeeding rates in the United States. Understanding the motivations or barriers to the practice can help clinicians and counselors find ways to improve these rates, she said.

“It’s my long term dream to help more patients,” Ojeda said, and research is the way to do it. “You can have an unlimited impact.”

Dr. Shawn Batlivala, associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology

Batlivala was enrolled in a program similar to the MSCI during his residency at the University of Florida, though he only completed the certificate program before leaving for subspecialty training. When UMMC started enrolling its first cohort, he jumped at the chance to finish.

A pediatric interventional cardiologist, Batlivala is full of ideas for clinical studies and research. He’s interested in evaluating new procedures and devices used in cardiac catheterization labs, like bioresorbable stents.

There’s “anecdotal evidence” that some of these techniques may work in the tiniest heart patients, he said, but clinicians need actual data to know for sure.

Batlivala, who is enrolled in the patient/health outcomes track, said that UMMC provides a unique opportunity to study the effectiveness of congenital heart defect screening. As the only pediatric heart center in Mississippi, UMMC receives patients with the most serious conditions.

Physicians can usually treat defects when diagnosed early, he said. If they find the condition months after birth, treatment options are more limited and patient outcomes are generally worse.

“If physicians do not catch a defect that should have been caught earlier, the damage has already been done,” Batlivala said. “By evaluating the effectiveness of our screening procedures, this saves time, saves money and has a broad impact on the health and outcomes for our patients.”

Batlivala’s motivation for becoming a physician and a clinical scientist is simple:

“No child deserves to be sick,” he said. “I want to make cardiology better, and clinical research allows that to happen.”

Dr. Hana Nobleza, assistant professor of neurology

Nobleza’s interest in clinical research was solidified during her residency at the University of Connecticut after asking a simple question.

“While rounding in the stroke unit, I asked the attending physician if the side on which the patient experienced the stroke can predict their need for a gastronomy tube,” she said.

The attending didn’t know the answer, but she suggested that Nobleza go and find out. Using data from the patient’s charts, Nobleza published two studies that were the first to address her particular question.

“It’s a fulfilling feeling,” she said.

Nobleza enrolled in the MSCI’s clinical trials track because she wanted more formal training on how to conduct her own trial and collect her own data, rather than relying on retrospective studies.

Nobleza is interested in collecting baseline data for a study on the use of gabapentin in traumatic brain injury patients. The medication could help manage neuropathic pain in these critically ill patients and limit the need to use opioids for pain management, she said.

MSCI students take a set of core courses in epidemiology, writing, statistics and responsible conduct, as well as others specific to their track. Nobleza said the classes are helping refine her skills.

“I have a better idea of whether certain research ideas are feasible or not and how to write my own grant proposal,” she said.