New grant makes real IMPACT on state's rural primary care

Weston Eldridge grew up in a town where his ailing father had two jobs and no doctor.

Although that has changed, there were no physicians in the small Madison County town of Flora at the time – a vacancy that became a tragedy once his father was diagnosed with melanoma.

“With two jobs, it was hard for my father to take off work and go to Jackson for treatment,” said Eldridge, who graduates this month from the School of Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. “I realize that his death could have been prevented if he had been treated early on and we had better access to health care.”

It was some years after he had already decided to become a physician that Eldridge lost his father to skin cancer; but his made him even more determined to practice family medicine in a place where families like his need them most.

Hoping that more medical students will also answer this need, Dr. Loretta Jackson-Williams and her colleagues are now better able to spread the word, thanks to the awarding last summer of a four-year, multimillion-dollar grant called IMPACT the RACE Rural Track Program.

“This is an opportunity to make a huge difference,” said Jackson-Williams, vice dean for medical education and professor of emergency medicine at UMMC.

“It can have a lasting impact on health care in this state. It allows us to do the work we’ve been talking about a long time.”

The award from the Health Resources and Services Administration, a federal agency, to the School of Medicine is, at $1.9 million a year, worth at least $7.6 million, not including a $5 million supplement the school is eligible for at the end of a year.

The purpose of the grant is explicit in its unabbreviated title: Improved Primary Care for the Rural Community through Medical Education.

It is making possible substantial changes in the courses all medical students take, including offering a curriculum focused on the rewards and challenges of rural health care.

As a girl growing up in Kokomo, a Marion County community between Tylertown and Columbia, Dr. Carolita Heritage witnessed, and lived with, some of those challenges.

Now an obstetrician-gynecologist in Brookhaven, Heritage saw the suffering of victims and their families in the aftermath of traffic accidents while working with her father and brother for a local volunteer fire department.

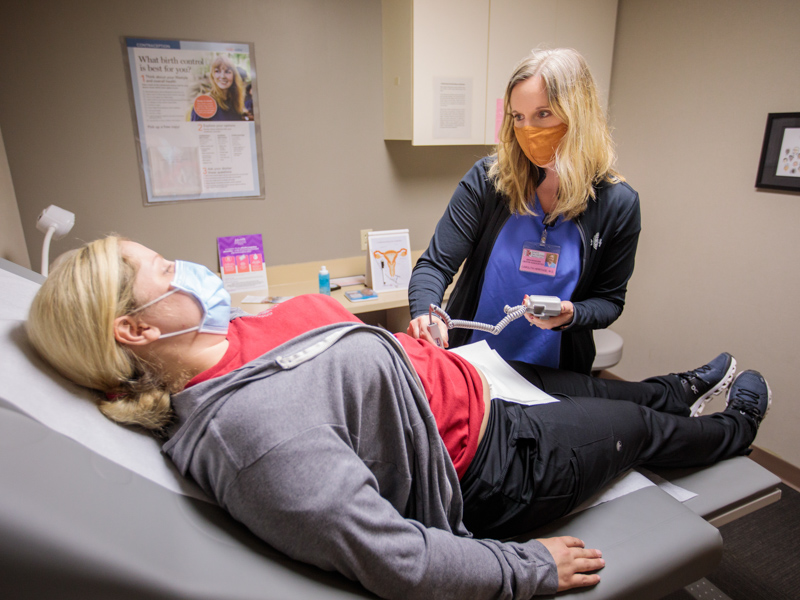

Weston Eldridge, a fourth-year medical student, plans to practice medicine in an area where doctors are needed the most, answering a need that a new School of Medicine grant is addressing.

“And I knew people who had to deliver their babies in cars,” said Heritage, a former Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar and 2015 graduate of the School of Medicine at UMMC.

Her own family usually traveled 12 miles to Columbia for their medical care, but had to drive her mother some 80 miles to the Gulf Coast for emergency heart surgery.

For those reasons and more, Heritage resolved to one day settle and practice in an area that needed more like her, especially in primary care specialties such as hers.

In the fall of 2019, she joined Brookhaven OB-GYN Associates, choosing a town located about halfway between her family in Kokomo and her husband’s family in the Canton/Gluckstadt area. Some of her patients drive to Brookhaven from Liberty and other small communities in bordering counties to have their babies, she said.

“There is always a need for primary physicians here. And, as it is with other specialties, many OB-GYN doctors in this area will be retiring soon.”

Heritage does her part to win over more medical students to rural health care by letting them shadow her, offering them an experience the Impact the Race grant is all about.

It is helping put more medical students in rural areas during their clinical training, connecting the School of Medicine with local physicians, and putting even greater weight on relationships between the school and rural hospitals and residency programs: For instance, medical students can now spend a significant portion of their clinical medical training in a rural setting such as UMMC Grenada or at Magnolia Regional Hospital in Corinth.

And there is much more, including enrichment of the Mercy Delta Express Project, which offers health-education services to school children in the Mississippi Delta.

Jackson-Williams is co-director of this work, along with Dr. David Norris, who says, “This is what Mississippi needs.

“The majority of doctors choose to serve in suburban and urban areas, but we need more primary care doctors on the front lines,” said Norris, professor of family medicine and assistant dean for academic affairs in the School of Medicine.

“City doctors may have an image of rural doctors that’s not the reality.”

Heritage would like to erase that image. “There is the misconception that you can’t make as much money, or that no specialists are here,” she said.

“But you can make a good living, and I see pediatric specialists about patients just about every day; so you do have that multi-specialty support here,” she said, noting that she delivers babies at King’s Daughters Medical Center, just across the street from her clinic.

For her part, she believes Impact the Race is “a great idea. When I was I medical school,” she said, “you didn’t have the opportunity to see how a clinic runs in a rural or underserved area unless you sought it out yourself, which I did.”

Through the work being done already with the grant, more students are seeing their future selves in those clinics.

“They’re realizing there is culture in ‘Small Town’, Mississippi, and that the patients who live there are engaged in their health care,” said Norris, who has noted these bonuses during visits with relatives in Sumrall, a Lamar County town of about 1,600.

They learn that, when you open a practice in a rural community, you automatically become a community leader, Jackson-Williams said.

“Everyone knows everyone,” Norris said. “The communities are a lot more close-knit than they are in cities and large towns. There’s more of a peace, I found.”

If so, the state is awash in peace. More than half of Mississippi’s residents live in rural areas, a condition noted by the HRSA in its decision to award this grant to the School of Medicine.

HRSA has also declared 80 of Mississippi’s 82 counties as medically underserved; and 94 percent of the counties as areas with shortages of primary care physicians, who practice family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics-gynecology, geriatrics and more.

These hardships have not gone unnoticed or untreated before now. The Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholarship Program and the Office of Mississippi Physician Workforce are also attracting more physicians, and future physicians, to rural communities.

“But there was a gap that hadn’t been addressed as much,” Loretta-Jackson said, “and that was in medical education.”

Norris believes exposing students to the lives led in these small settlements will trigger the “white knight complex” that is the mark of physicians and physicians-to-be.

“They realize they can become part of the solution,” he said.

They may find that they want to serve people who, often, have little or no transportation, who have to hold down more than one job, who endure a general lack of preventive care.

“When you’re not living there, it may not be clear to you what limitations those patients face,” Jackson-Williams said.

It’s important for all students to be clear about this, Norris said. “Even if you don’t plan to practice rural medicine, just knowing, as a doctor, the realities of what hospitals in these areas can and can’t do is valuable.”

It’s valuable, Jackson-Williams said, because, no matter where you practice in Mississippi, even in a city or a large town, you will be consulting with physicians whose patients live in those underserved neighborhoods.

But Dr. Sheree Melton believes more students are going to want to live in or near those neighborhoods.

“Already, some students who have worked in rural hospital systems have signed contracts with them,” said Melton, assistant professor of family medicine and the clerkship director for the Department of Family Medicine at UMMC.

“They’ve agreed to come back there and practice for a certain number of years once they’ve finished their residency training. They already have a job before they graduate from medical school.”

Eldridge, for one, has a job waiting for him in the Winston County town of Louisville. “I signed a contract,” he said.

Even as a first-year student, he was getting a preview of life as a provider for underserved patients by signing up for School of Nursing-run health fairs and school-based clinics.

“We did wellness exams at this elementary school – a lot of bellyaches and earaches,” Eldridge said. “Sometimes it was just little children who needed to be loved on. I had such a great day.”