#UMMCGrad18: For future ophthalmologist, the big picture is clear

Salma Dawoud has had two supremely moving experiences, which were exactly that: moving from the heat of Kuwait to the cold of Canada and from there to the unexpected warmth of Mississippi.

“When my family came here, I thought it was the tragedy of my life,” said Dawoud, who graduates from the School of Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center on May 25. “But it’s a great thing that happened to me.”

A Palestinian by heritage, a Kuwaiti by birth, the former Ontario resident said living in such conflicting cultures opened her eyes – not a bad thing for a future ophthalmologist.

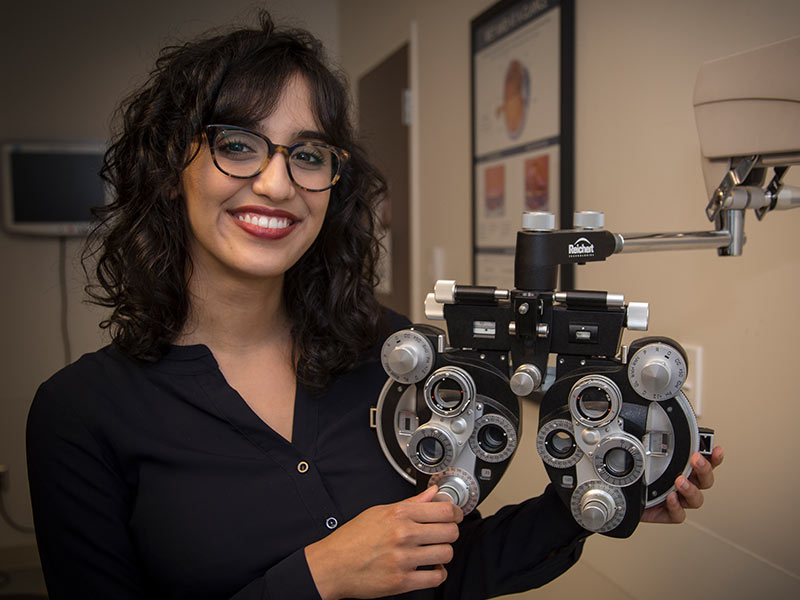

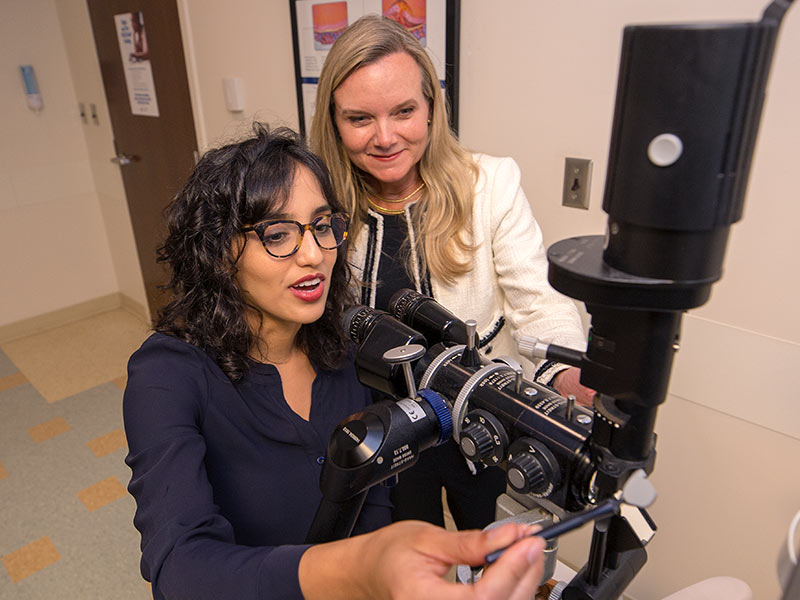

In January, Dawoud secured an early match for her residency with the University of Iowa, which has one of the top-rated ophthalmology programs in the country, said Dr. Kimberly Crowder, UMMC professor and chair of ophthalmology, and one of Dawoud’s mentors.

“Since I’ve been here, from the mid-1990s, Salma is, to my knowledge, the first student from here to match there in ophthalmology,” Crowder said. The 2017 U.S. News & World Report Ophthalmology Rankings listed the University of Iowa at No. 6, tied with Duke University Eye Center.

“It’s a fabulous program; she’s going to do well,” Crowder said. “Maybe they won’t keep her in Iowa and let her come back here.”

That would be a coup, considering that, as a teenager, she had balked at coming here in the first place.

“It was a bigger culture shock for me moving to Mississippi from Canada than it was moving to Canada from Kuwait,” Dawoud said.

Of her life in Kuwait, Dawoud remembers only a few savory bits and pieces – as in pieces of Kanafeh, a dessert described by Saveur magazine as “baklava meets mozzarella sticks.”

She was 6 when her family set out from the Middle East for Canada so her father could work on his Ph.D. at the University of Waterloo. The son of Palestinian parents, her father later explained to his children that, for someone not born in Kuwait, it was harder to earn an advanced degree there.

“A lot of women in the Middle East study medicine,” said Dawoud, whose older sister Reem is a medical student at Emory University. “But coming to North America helped us. It would have been difficult financially to do that in the Middle East. I don’t think I would likely be a doctor if I had stayed there.”

Sometimes, she wondered if she should be a physician anyway. “There were rare moments in medical school when I was tired; it wasn’t that I didn’t want to do medicine anymore. I didn’t want to do anything anymore,” she said.

“But then I remembered that, as a Middle Eastern woman, I could still get as educated as I want to be. I got to go to medical school; I feel very grateful.”

That gratitude extends to her parents. “They did everything they could to set us up for life,” Dawoud said. “That’s why my dad got his Ph.D.

“My mom brought up four children like a champion. Before we left for Canada, I remember her buying me a red jacket that matched my older sister’s. It was the thickest she could find in Kuwait.

“It was fine in October, when we arrived. But in December – I had never experienced cold like that.”

The family endured the winters of south-central Ontario until Salma was a teen. Long before then, the native Arabic speaker had learned English.

“We have patients at the Medical Center who speak Arabic,” Dawoud said, “and even though I’m not an official translator, I talk to them in Arabic; it makes them more comfortable to hear someone speak their language.”

This may be a case of exemplifying “humanistic patient care,” a standard for induction into the Gold Humanism Honor Society. To Crowder, it was no surprise that Dawoud has been so honored by her peers.

“She does everything she can to put patients at ease, which makes her well-liked by attending physicians,” Crowder said. “She is the total package: smart, kind, friendly, engaged. You feel good at the end of the day when you work with her.”

Dawoud was first exposed to this kind of work in Jordan, which she would visit and where she shadowed an immunologist who was also her uncle.

“My interest in science and the fact that there’s a lot of interaction with people – that is what drew me to medicine,” she said.

“One reason I chose ophthalmology is because it’s mostly about helping patients improve their lifestyles, said Dawoud. “Even if it’s not life-or-death, it’s an important part of how people live their lives.”

Dawoud’s own life in Canada ended when she was 16; that’s when her father accepted a teaching job in computer engineering at the University of Southern Mississippi. In Hattiesburg, she feared she would face a close-minded culture. What she found mostly, she said, was curiosity about her heritage, along with some friends, especially after she entered the college where her father taught.

“If you had told me when I was a child that I would become best friends with someone from Small Town, Mississippi” she said, “I would have been freaking out.” Here, she did witness some of the poverty she expected to see in this mostly rural state.

“One thing I learned from living in different countries is that I can feel very strongly for people who feel excluded,” Dawoud said, “because I have felt that way sometimes.

“As I child I also discovered that if you’re learning another language you have to notice people’s moods and facial cues. Because sometimes that’s the only way you know what they mean.”

She brought this empathy with her to medical school and, particularly, to her volunteer work at the student-run Jackson Free Clinic.

“You’re seeing patients there who have no insurance,” Dawoud said. “When studying got old, you got to go to the clinic, see them, take their blood pressure and help them.

“In the clinic, you can make a difference. This is why I’m doing medicine.”