Genetic discovery uncovers answers to one patient’s lifelong health questions

After years of living with a debilitating disease, Brian McDade of Clinton is finally making sense of a mysterious illness that has afflicted him his entire life.

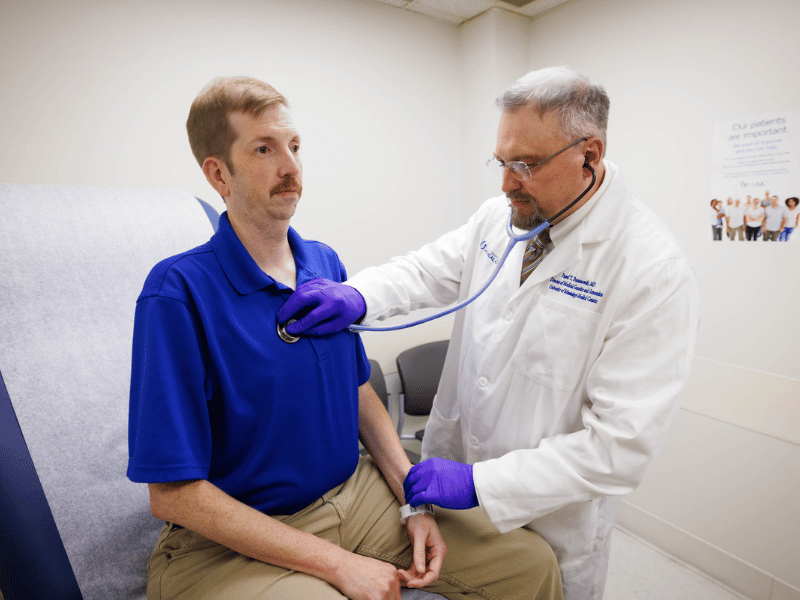

With the help of the newly-established Division of Genetics and Genomics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, McDade, 42, was diagnosed with the multi-symptomatic genetic disorder, Barth Syndrome.

Barth Syndrome is a rare chromosomal disorder that affects around 200 people worldwide. The X-linked genetic disease occurs almost exclusively in males, with females as carriers. It is almost always found in infancy or early childhood. But for McDade, the root of his chronic health complications would remain a mystery well into adulthood.

“I was born with holes in my heart,” said McDade. “I was in the intensive care unit for the first three weeks of my life.”

When Dr. Pawel Pomianowski joined UMMC as the new medical director of the Division of Genetics and Genomics, McDade would get the answers he had been seeking his whole life. And what might have otherwise been an unfortunate diagnosis mostly brought relief.

“When my cousin’s son was born a couple of months ago with Barth, I had a feeling my situation was related. But no one could tell me for sure. When Dr. Pomianowski confirmed I had Barth Syndrome, I was just happy to have answers for the way I’ve been feeling all my life,” said McDade. “I have been blaming myself for so long for the things I couldn’t do. And this diagnosis explains so much for me. I don’t feel alone in this anymore.”

The most frequent symptom of Barth Syndrome is cardiomyopathy, which affects 70% of patients with the condition in the first year of life, with 12% requiring a heart transplant. The median age of those recipients is 1.7 years old.

“I know lots of kids who have had a transplant before 16-years-old,” said McDade. “I was even lined up to get one myself at one point.”

“For this condition, this is a mild form,” Pomianowski said. “Many patients with Barth Syndrome do not make it out of adolescence.”

With routine visits to his cardiologist and the use of several heart medications throughout his childhood, McDade’s heart problems seemed to be well under control. But just a few days into his freshman year of high school, he would have his first real scare with the illness.

“I got sick at school, and I started throwing up,” he said. “I thought I had a stomach bug. I went home and was sick for several days. I had a high fever. I didn’t feel well. I couldn’t eat.”

When the symptoms didn’t subside, a visit to the doctor revealed something much more serious.

“I’ll never forget the way the physician looked at me and goes ‘Your body is in shock,” said McDade. “The next thing I know, they’re strapping me to a metal table and giving me IVs. They put me on a gurney and then I was on my way to UMMC. And that’s when they told me that I was having congestive heart failure. I was 14 years old and scared to death,” he said. “All I knew was that they were talking about a heart transplant.”

After spending the night in the hospital, awaiting an emergency transplant, what McDade describes as “an act of God” occurred.

“By that next morning, I had done a complete 180,” he said.

Four years later, at 18, McDade was rushed back to the Medical Center after sampling his first cigar left him in a dire condition.

“It turned out that I had ventricular tachycardia (or v-tach) and they had to shock me with those pads to bring me out of it,” he said. “It was at that point that the doctors and my parents decided I needed a defibrillator. The doctor explained that if this occurred again, I wouldn’t make it to a hospital. I wouldn't suffer from a heart attack. My heart would take in more blood than it could get out and essentially explode.

“I went in Sunday to get the heart catheterization done,” he said. “I woke up Tuesday with a big patch on my chest, sore as could be, didn’t know where I was and then was informed that I had a pager-sized device with a cable connected to my heart inside my chest.”

McDade said that for years he resented not having a choice in the matter, particularly after a few bouts with “false alarm” shocks from the device. Over two decades after it was installed, he expressed to his doctor that because he had not had another v-tach episode in that time, he would rather it be removed. But just months before the surgery, he found himself very grateful for the device.

When driving down the road, after making a supply run for his dad’s 69th birthday party, he felt tingling all over his body—what he knew well by now as the precursor to a shock from the defibrillator. Realizing this, he was able to pull to the side of the road before passing out.

“When the fire department arrived, I was in tachycardia, so my heart rate was over 100,” he said. “I couldn’t settle down. But the defibrillator wasn’t hitting me anymore, so I was okay. When I got to UMMC, and they read the device, they confirmed that I had ventricular tachycardia, and the two shocks got me out of it. That was sobering.”

In a follow-up appointment with Dr. Gabriel Hernandez, professor of cardiology and an advanced heart failure specialist, McDade was given a pulmonary stress test where he was attached to a heart monitor while peddling a stationary bike.

“I only made it four and a half minutes,” he said. “But it wasn’t my heart giving out on me; it was my thighs.” McDade said the cardiologist was puzzled, given that the cause of his weakness wasn’t heart related.

This wasn’t new to McDade. When he was in his thirties, he said he began to focus a lot more on his health, trying to get regular exercise. When running with his friends, he said that he was always frustrated that he was worn out a lot more easily than everyone else.

“I graduated high school weighing 96 pounds,” he said. “I was always skin and bones, never built much muscle. But with the heart disease, we never thought I was going to be some star athlete. So, I don’t know how much we assumed that this was just part of living with a heart condition not knowing that there was the skeletal myopathy part of Barth Syndrome that was absolutely playing its part in all of that.”

After being referred by Dr. Lampros Papadimitriou, professor of cardiology and an advanced heart failure specialist, McDade is now able to connect with other patients through the Barth Syndrome Foundation, even meeting a couple of young men in the Jackson area. Fully immersing himself in his new-found community, McDade will attend the International Barth Syndrome Conference this summer, accompanied by Pomianowski.

“We want to learn everything we can about it,” said Pomianowski. “We’re thinking of building a clinic to connect these patients, and I think it’s very important that we attend events like this to find out how to support them in every way that we can.”