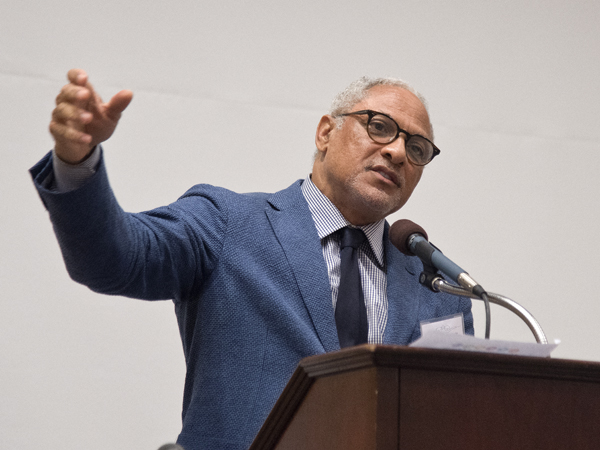

Mike Espy, Edelman lecturer: U.S. food policy is not health policy

Government programs that have benefitted those who grow food and those who process it haven't necessarily benefitted those who eat it, said Mike Espy, former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, speaking Tuesday at UMMC.

Espy, an attorney and the former U.S. Representative for the state's 2nd District, was the distinguished guest lecturer for the third annual Marian Wright Edelman Lectureship, which focused on the ways official food policies in America can affect consumers' health.

Espy, who was a member of President Bill Clinton's cabinet from 1993-1994, noted that more than two-thirds of adults in the United States are overweight and obese, that “poor diet is a major risk for weight gain,” and that Mississippians in particular “lean toward fried foods, fat foods, sweet foods.

“We are eating ourselves to death,” said Espy, a Yazoo City native who said adults, including himself, don't easily grow out of lard-laced, sugar-spiked childhoods.

“Habits die hard,” he said. “These foods are available, these foods are cheap.”

One reason for this dietetic disaster, he said, is the fact that, in the United States “neither [farm policy nor food policy] has anything to do with health policy.”

Provisions in the U.S. Farm Bill, first passed during the Great Depression and renewed or updated ever since, offer benefits to farmers that were intended to create prosperity for the nation's food growers and develop a cheap food supply, Espy said.

But these allowances, including subsidies and other considerations, have encouraged farmers to grow crops that include corn, sugar and wheat; these often end up as highly processed foods, such as sugary cereals, donuts, and high-fructose corn syrup - a common sweetener in soft drinks - all of which can contribute to weight gain.

“But I see the sun bursting through,” Espy said, referring to actual and potential changes to these policies.

With recent reforms, the federal government is encouraging the production of many more types of crops, including fruits and vegetables, he said.

And, because subsidies are so expensive to maintain, more reforms may be afoot as more fiscally-conservative candidates are elected to Congress. Programs such as the Farm Bill “aren't as sacrosanct” any longer.

Still, Espy said, “we have a lot to do.” One of his proposals is a change in the Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) system, part of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) that enables low-income families to buy groceries with government funds deposited into an account.

“The government pays for that, but the government also pays for negative health outcomes,” Espy said. Purchases of tobacco and beer are not allowed with the EBT card, which is like a bank debit card. But what about sugary drinks? he said. “What about Cocoa Puffs?”

Rather than disallowing such purchases, he suggested adding value to an EBT card when a consumer uses it to buy more fruits and vegetables.

“It's your decision,” he said.

Presented by the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute for the Elimination of Health Disparities and Mississippi State University, the lectureship also featured Reena Evers-Everette, executive director of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute in Jackson; Dr. Bettina Beech, dean of the School of Population Health and executive director of the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute; and speaker Dr. Daniel Remley, field specialist in food, nutrition and wellness, Ohio State University Extension.

“Diabetes and food insecurity go hand-in-hand,” said Remley, noting that the creation of food pantries that offer healthy choices to clients can promote long-term food security and address the risk of chronic disease for low-income families.

Some 80-90 people attended the event, which wound up with a panel discussion moderated by Dr. Leslie Hossfeld, professor and head of MSU's Department of Sociology.

Along with Espy, the panel featured Dr. Gregory Bohach, vice president of MSU's Division of Agriculture, Forestry and Veterinary Medicine; Dr. Dolphus Weary, president/co-founder of the Rural Education and Leadership Christian Foundation, based in Richland; and Oleta Fitzgerald, Southern Regional Director for the Children's Defense Fund office in Jackson.

Responding to a question about ways to provide access to healthy food for everyone, Fitzgerald said one answer lies in educating children about good nutrition. “An educated population becomes a self-sufficient population.”

She also recommended expanding Medicaid, which “could help tremendously, especially for the elderly and those without access to health care.”

The lectureship series is named for Marian Wright Edelman, president and founder of the Children's Defense Fund. Begun in October 2014 by the Office of Population Health and the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute, the series presents distinguished educators, scientists and child advocates, who discuss research and policy issues concerning child health and health disparities. It is open to all university students, faculty and the general public.

For more information on the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute and its programs, go to www.umc.edu/evers-williams.