Sickle cell trait could alter diabetes test results

Researchers from Brown University and the Jackson Heart Study say that physicians should be aware of new findings about a blood test used to monitor diabetes. The results could mean missed chances to treat diabetes in African-Americans with a common genetic trait.

University of Mississippi Medical Center scientists co-authored the study, published Feb. 7 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The results show that in people with the same fasting glucose level, sickle cell trait is associated with a lower than expected hemoglobin A1C, or HbA1c.

Diabetes is an important and prevalent risk factor in the Jackson Heart Study, said Dr. Adolfo Correa, UMMC professor of medicine, JHS director and co-author of the paper.

“If not controlled, diabetes over time will result in damage to the heart, kidneys and eyes, as well as cause unhealthy levels of cholesterol and blood lipids, high blood pressure and reduced cardiovascular health,” he said.

The JHS is a collaboration between UMMC, Jackson State University and Tougaloo College. It is the largest study of African-American cardiovascular health, following 5,300 community members since 2000.

This recent paper studied 4,620 people from the JHS and the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, or CARDIA, with similar fasting and two-hour blood glucose levels.

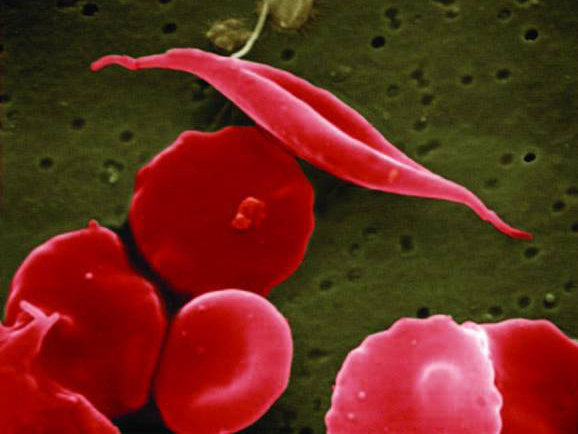

One in 12 African-Americans have one copy of the gene that causes sickle cell trait, or SCT. Sickle cell disease is the chronic condition caused by having two copies of the gene. SCT has been considered relatively benign, though another JHS study linked SCT to increased kidney disease risk.

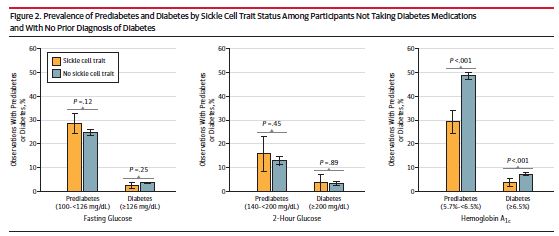

The study compared people who had no prior diabetes diagnosis or weren't taking diabetes medications. Using HbA1c as a standard to define diabetes status, 48.6 percent of those without SCT had prediabetes, compared to 29.2 percent of those with SCT. Meanwhile, 7.3 percent of those without SCT met the criteria for diabetes, compared to 3.8 percent with SCT.

This difference could mean that patients and physicians are missing opportunities to treat or prevent diabetes.

“If you are African-American and have diabetes or are at-risk for diabetes, you should know that your A1c results may not accurately reflect your blood sugar control,” Lacy said. “It might be helpful to have your doctor test your blood sugar using both A1c and glucose measures.”

Doctors use blood glucose and HbAlc to diagnose diabetes, but they represent different things. Glucose is sugar dissolved in your blood. Its concentration changes quickly, depending on when and what a person last ate.

HbAlc is a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to the body. Its levels usually correlate with average blood glucose levels over the past two to three months. Consistently high blood glucose will raise HbA1c. In addition, HbA1c doesn't require fasting for a reliable reading. That makes it useful for tracking glucose control in diabetes.

Why might HbAlc measurements be lower in African-Americans in SCT? The authors have two ideas. One is that SCT red blood cells could have a shorter life span. Less time to accumulate HbAlc may lead to lower levels that don't match the fasting glucose. The second possibility is that the difference is due to interference with the measurement method.

“Studies done in the past have indicated that [red blood cells] in persons with SCT do not have a shorter lifespan,” said Dr. Joseph Maher, a UMMC professor of medicine who studies sickle cell disease. However, those studies were small and the more work should be done to know for sure.

Maher, who was not involved in the study, said it is possible there is “some unknown biologic difference between SCT and No-SCT [people] regarding glucose metabolism [because] there are such differences between black and white patients.”

“Earlier studies have shown that African-Americans overall have higher levels of HbA1c compared to their blood sugar levels than white individuals,” Correa said. However, such studies did not examine this relationship in the presence and absence of SCT. The cutoff for diabetes that doctors should use may differ with race and SCT status, he said.

Furthermore, “many people have sickle cell trait and do not know it,” Lacy said.

“It would appear beneficial for black patients with diabetes mellitus to be tested for SCT and have the results included in their medical record,” wrote Drs. Anthony Bleyer and Joseph Aloi of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine in an editorial for JAMA. “Testing could aid in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, as well as aid in a patient's general health care.”

Lacy, whose dissertation is on improving diabetes screening and diagnosis for African-Americans, said that one of the next steps is to study the consequences of the findings.

“We [want] to examine whether or not the underestimation of A1C in those with sickle cell trait is leading to a delay in diabetes diagnosis and subsequent increase in risk of diabetic complications,” she said.

“Until these additional studies are done, the best test to guide diabetes care in African-Americans is probably the fasting blood glucose,” Correa said. However, he said, “African-Americans with hemoglobin A1c levels that are quite high clearly do have diabetes that should be treated more aggressively.”

UMMC faculty and JHS investigators Dr. James Wilson, professor of physiology and biophysics and Dr. Solomon Musani, associate professor of medicine, are also co-authors. Funding for the JHS comes from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.