Oral cancer patient fights to earn 'Survivor' title

When Jennifer Johnson noticed the small, bleeding bump on her upper right gums in 2012, she was experiencing one of the most difficult situations in her life - her father had been diagnosed with stage IV cancer, and his condition was critical.

When the appearance of the lump changed a week later, she knew something was not right.

“It was like a black spider had plastered itself in my mouth, and it had like a little black spot with little legs coming from it,” Johnson said.

A full-time student at Mississippi State University from Columbus, Johnson was seeing a doctor at the campus student health center for her blood pressure. She arranged for Johnson to see an oral surgeon in Columbus.

“I explained to him that I needed to take care of dad first,” Johnson said. The surgeon told her, “No, let me take care of you first.” He performed a biopsy that day.

After the biopsy was sent to the lab for testing, Johnson was sitting by her father’s bedside. His cancer was terminal.

“I was talking to my dad before he died, and he hadn't said anything for days,” Johnson said. She told him, “Dad, I think it's bad.” He replied with one word, “Fight.”

“So, I decided that I was going to fight, no matter good, bad or ugly. No matter how many years, I was going to fight and do whatever I had to do to make sure that I was around for my family,” Johnson said.

Her father passed on November 23. Five days later, on what would have been her father’s 76th birthday, Johnson was in her mother’s back yard with her sister and mother making arrangements for her father’s funeral. It was then she got the news. The lesion was cancerous.

“At that moment, just the ‘Big C’ changed the whole world,” Johnson said. “It was like I was standing in the back yard, and I could see images floating around me. You never think it can happen to you, but it can.”

Johnson was referred to the University of Mississippi School of Dentistry Department of Oral Oncology and the Interdisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Team at the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Cancer Institute for her care planning.

“When I landed at UMMC, I immediately felt like this is where I needed to be,” Johnson said. “I had what I called ‘Jennifer's Team.’” Not incidental, the interdisciplinary team structure helps limit the number of visits for testing and consultation and, when possible, bringing the specialist to the patient through a primary physician.

The team at the Cancer Institute includes medical and radiation oncologists, surgeons, pathologists, neuro-radiologists, nurses, speech pathologists, dietitians, social workers, dentists and any other specialist the patient might need specific to their case.

One member of Johnson’s team was head and neck surgeon Dr. Gina Jefferson, an associate professor of otolaryngology and communicative sciences.

“Not just for oral cancer, but for all head and neck cancer, we have a weekly head and neck tumor board so we can develop the best treatment plan for the patient,” Jefferson said. “We base our treatment decision-making on the National Cancer Center Network guidelines. The benefit is that the patient is getting a full team to collaborate and determine the best treatment so there is no bias to one treatment method for patients.”

It was Jefferson who outlined Johnson’s treatment plan to her. Surgery was the best course of action, but it would require intensive therapy that involved removing bone, teeth and oral tissue and rebuilding with bone and tissue from other parts of her body. The treatment would span years.

“All the words were so overwhelming to me at that moment that it took a while to absorb it,” Johnson said. When Jefferson asked if she were okay, Johnson said, “I can do this. My dad told me to fight, and I have to fight.”

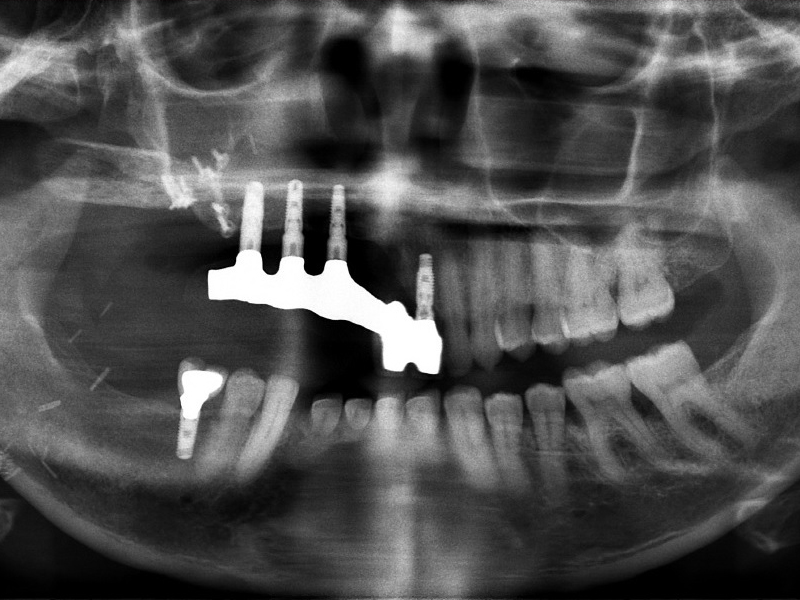

And fight, she did. Jefferson and the oral oncology team removed all of the affected tissue, along with her teeth, and rebuilt Johnson’s jaw from her fibula. Tissue from her thigh rebuilt her cheek wall and the roof of her mouth. She had to learn to walk and talk again. She received nutrition from a feeding tube. Yet, in all of that, she made sure she completed her classes at MSU.

“I wish my husband had taken a picture,” Johnson said. “I had a cast on my leg, a feeding tube in my nose, and I was at the computer banging away, writing papers. I finished those classes. August 2013, I was back on campus. I wasn’t giving up.”

Two years after the surgery, the oral and maxillofacial surgery team at the School of Dentistry installed dental implants in the healed, implanted bone.

“When they did the install and I could smile, I was on cloud nine,” Johnson said.

Not every patient’s head or neck cancer is resolved through surgery like Johnson’s. Many require chemotherapy and radiation therapy as well. Dental health may not be the first thing on a patient’s mind when hearing a cancer diagnosis.

“It may not be something that you, necessarily, think about,” said Dr. Robert Hamilton, associate professor of medicine who specializes in head and neck cancers and hematology/oncology. “But, dealing with cancer patients all the time, [dental health] is very important to us.”

Hamilton cares for patients with cancers of the head and neck. He said that many have to be seen and cleared by oral oncology, conveniently located near the Cancer Institute at the Jackson Medical Mall, prior to beginning radiation therapy. “It’s a vitally important part of taking care of that group of patients,” he said. “Maintaining proper nutrition is very important in a cancer patient.”

Before receiving radiation therapy or chemotherapy, patients are referred to oral oncology to head off a myriad of complications that can result from cancer treatment. Dr. Kevin Nelson, assistant professor of advanced general dentistry, determines which teeth might cause a problem and require extraction.

“There are a lot of oral complications that come along with head and neck radiation,” Nelson said. “A high dose of radiation to the jaw takes away a lot of the healing properties in the mouth.”

He said that one of the biggest complications is osteoradionecrosis, bone death due to radiation. He and his team evaluate the patient’s teeth to diagnose early any teeth that might cause problems after treatment begins.

“If they come to me after to have a tooth extracted from a bone that has had high dose radiation, I take that tooth out, the jaw doesn't heal properly and the bone is exposed in the mouth,” Nelson said. “It affects the patient's quality of life. It can progress to the point where they could lose their jaw in worst case scenarios.”

Radiation therapy also compromises the salivary glands, causing dry mouth. Nelson said that dry mouth causes increased dental caries. Mucositis occurs when the radiation beam affects the soft tissue around the teeth, causing inflammation, pain and difficulty eating.

“Cancer patients need to keep eating, and we certainly don't want any interruptions in their chemotherapy,” Nelson said.

Treatment of bony metastasis in patients with head and neck cancers can also pose a risk for loss of the mandible. A common treatment method is bisphosphonates, a drug that Hamilton said works by attracting calcium to the bone, and denosumab, which inhibits the destruction of certain types of bone cells.

“When we do a dental evaluation on someone who is about to begin bisphosphonate, we want to take out any teeth that might be a problem after they get on that drug,” Nelson said. “After they are on the drug, we need to avoid all invasive dental procedures: no extractions, no removing of any bone in the mouth.”

He said that, for a patient on bisphosphonates, simply eating a corn chip wrong or having a denture rub can cause exposed bone in the mouth that can become infected and painful.

For Johnson, Nelson and the staff at the oral oncology clinic provide continued follow-up care post-treatment. She visits the clinic every six months to ensure that her cancer has not returned and that the tissue surrounding her dental implants is healthy.

“I know one thing, even though my progress is so good, I don't ever want them to turn me loose,” Johnson said. “I'm a patient for life. I'm happy. I cannot tell you how much oral oncology means to me.”