New study examines impact of race on chronic pain disparities

As a postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Matthew Morris studied pain and sensitivity in otherwise healthy Black and white children.

He was shocked by the vast differences along racial lines, and curious to learn why.

A decade later, the associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior is principal investigator of a five-year, $3.3 million study he hopes will explain how social and biobehavioral factors contribute to a greater risk of transitioning from acute to chronic pain following a traumatic orthopedic injury in Black patients compared to white patients.

While acute pain ends after an injury heals, chronic pain, which continues long after treatment, can last months or years, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Chronic pain is linked to depression and one of the top reasons people seek medical attention.

“There is a long history of false beliefs regarding non-Hispanic Black individuals exhibiting greater pain tolerance than non-Hispanic white individuals, and therefore having less need for medications that could manage their pain,” Morris said. “These historically-rooted beliefs are still held by some medical students and physicians, and likely contribute to racial disparities in pain management. The research we are conducting seeks to dispel those false beliefs.

“In fact, evidence suggests that the lived experiences of non-Hispanic Black individuals, which includes greater exposure to stressful and traumatic events across the lifespan, are actually associated with greater – rather than less – pain sensitivity.”

The Acute to Chronic pain Transition and Race study (ACTR) study, funded by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, will recruit 300 patients – half Black, half white – with traumatic orthopedic injuries and assess pain outcomes during hospitalization and monthly follow-up visits.

“It is well documented that Black patients have more chronic pain and more disability due to chronic pain,” said Dr. Cindy Karlson, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior and co-investigator. “This study will be an important step toward understanding why these disparities exists.”

In the United States, traumatic injuries cause more than 30 million trips to emergency rooms and 2.5 million hospitalizations every year, according to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

With a multidisciplinary research team from the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and University of Alabama at Birmingham, ACTR has begun recruiting patients.

Dr. Patrick Bergin, associate professor of orthopedic surgery and rehabilitation, said his role as co-investigator is to help identify eligible patients and determine those at high risk of chronic pain.

“The injuries we’ve chosen have been reviewed in other large prospective studies because of their propensity to cause chronic pain,” said Bergin. “Chronic pain, apart from the intrinsic suffering, can make it difficult to remain employed or enter the work force and can damage interpersonal relationships.

“If we can identify risk factors for chronic pain development and come up with solutions to prevent it, we can help improve people's lives.”

During phase one, researchers will identify similarities and differences in how biobehavioral factors including depression, posttraumatic stress, inflammatory biomarkers, and treatment expectations affect chronic pain in both groups. Phase two will focus on the impact of social factors like greater life and neighborhood stress and lower socioeconomic status.

Before patients undergo surgery, researchers will collect blood samples, which Dr. Gailen Marshall, R. Faser Triplett Sr. MD Chair of Allergy and Immunology, and his lab will use to examine levels of inflammatory biomarkers responsive to both acute stressors and injury that are elevated among people with chronic pain.

“There is a spectrum of immune/inflammatory effects to the same stressor – such as acute trauma and chronic pain – among different people just as there are different psychological responses,” Marshall explained. “Predicting who responds in a specific way to chronic stressors has tremendous therapeutic potential for patients with inflammatory dysfunction.”

As executive director of the UMMC Human Immunology and Inflammation Biomarker Core Laboratory, Marshall has extensive experience analyzing samples.

“The relationship between psychological stress and pain is a ‘two-way street,’ that is, the greater the stress, the higher the perception of pain and vice versa,” said Marshall.

Still, the role inflammation plays is unclear. Marshall believes this study will help establish the relationship between chronic pain and stress and identify an immune/inflammatory biomarker profile related to the risk for developing chronic pain.

“If so, future studies may be able to use these profiles in predicting patients at greatest risk for developing chronic pain with the ultimate goal of intervening to prevent rather than just treat the chronic pain syndrome,” said Marshall.

Karlson, also director of Inpatient Pediatric Psychology Services in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hematology/Oncology, said while ACTR focuses on adults, it may also help pediatric patients, many of whom spend years trying to get a medical diagnosis and “fix” their pain.

Because chronic pain is so complicated, treatment for both children and adults often involves a multidisciplinary specialty pain clinic.

“Childhood pain often continues into adulthood,” said Karlson, “so, it is extremely important to get comprehensive treatment as soon as possible.”

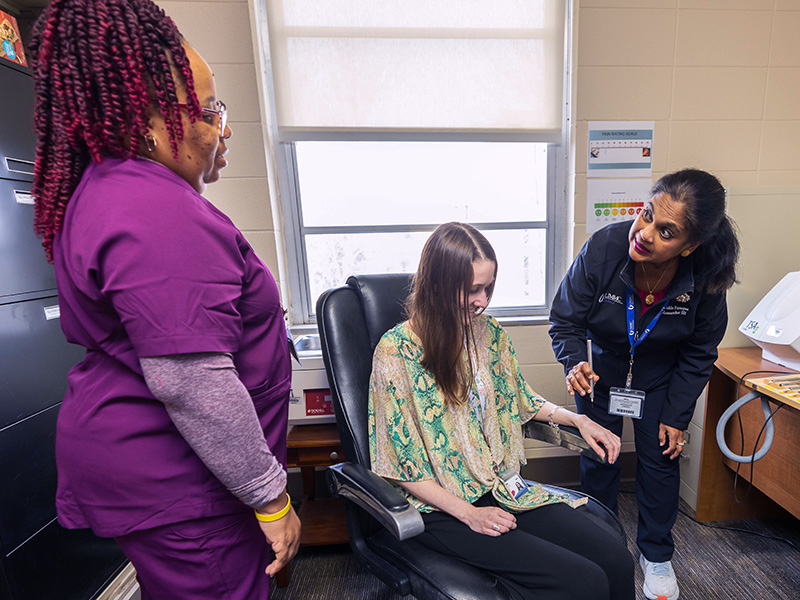

The multifaceted study will also use quantitative sensory testing to evaluate how patients respond to sensations. For example, using a type of pinprick stimulator, they will apply different amounts of pressure to the skin to examine pain sensitivity to provide insight into the patients’ pain experiences.

“We hope that improved understanding of these disparities in pain experiences, including emphasis that they emerge from lived experiences and not innate biological differences, can promote more equitable management of pain in health care settings,” said Morris.