Argentina 'door to Olympics' for UMMC couple

Like most competitors, they came away without medals.

But swimming for Argentina's national team in the Olympics is a life milestone for Dr. Luis Juncos, UMMC professor of nephrology, and his wife Valentina Juncos, an Epic senior analyst.

Luis Juncos was a member of Argentina's delegation in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles; Valentina Juncos, at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. Both were championship swimmers in South America and their home country.

As she's watched this year's Olympic competitions, “when I look at the pool and the swimmers, it feels like it was back then, but the technology has improved so much,” said Valentina Juncos, who competed at age 21 as she was transitioning from her home country to studies at the University of Michigan. “You watch an event, and then you can go back on your phone and watch it again.”

Luis Juncos in 1984 was in his third year of medical school at the Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, where his studies competed with his twice-daily swim practices. “I was past my peak, but I was No. 1 in Argentina and No. 2 in South America,” he said.

Their paths first crossed in the early '80s when they both swam for their home country. Then in March 1984 - just months before Luis left for the Olympics - the two were in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, swimming in the South American Championship.

“We started dating during the championship in Rio,” Valentina remembered.

From there, they went on to realize their Olympic dreams. “It was a big goal for me as a child,” said Luis, who began competitive swimming at age 10.

“I started to swim at age 5 or 6, and competitively starting at the age of 9. The first time I qualified for the national team in 1982, I was 15,” Valentina said. “Until 1988, I was on the national team and participated in swim meets all over the world.”

Luis competed in the 100-meter butterfly and the 200-meter individual medley. Racing six-tenths of a second faster or slower made all the difference then between qualifying for the consolation finals - there were no semifinals at the time - or ending up 30 to 40 places lower, Luis said.

“I did so-so,” he said of his overall performance. “It's very competitive. I came in in the high 20s in my positions. Six-tenths of a second slower, and I would have been about 80th. It's so tight. Small differences are huge, like your stroke and start and turn.”

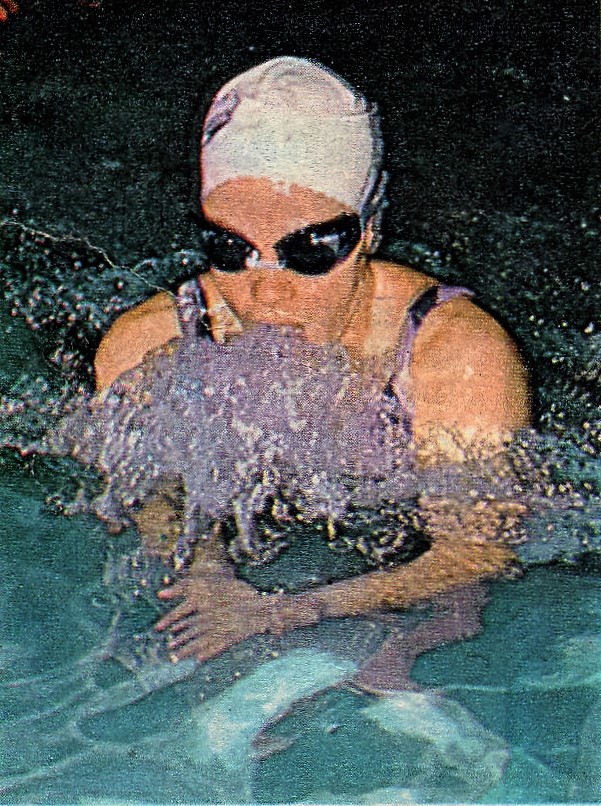

Valentina swam in the 200- and 400-meter individual medley and the 100- and 200-meter breaststroke. “I did not do my best,” she said. “My times were not my best. I'd say the best I had was in the 200 medley. I came in 29th.”

But his wife faced obstacles that affected her performance, Luis said. “She didn't do nearly what she is capable of,” he said. “We'd just been married for a couple of months. We had moved to Detroit, so she wasn't with her club and couldn't get access to adequate facilities for well over a month. She went to the Olympics without being able to prepare like she'd been able to prepare for other competitions - and this was just one year after she came in fourth in the Pan American Games in Indianapolis.”

The road to the Olympics was paved with sacrifice and sweat, Valentina said. “It's hard to explain. It's a whole process you go through,” she said. “It's not like one day you find yourself at the Olympics. A typical day was six hours of training. Getting up at 4 a.m. to train takes a toll on your brain more than your body.

“But it was one of the goals I wanted to reach, and I accomplished it,” Valentina said. “I was walking in the opening ceremonies of the Olympics when it really sank in.”

After the Olympics, Luis retired, but kept swimming a couple of hours a day. He would intermittently increase his training in order to swim in a number of international meets, including the World University Games in Japan, but the rigors of his medical training curtailed travel and time in the pool. “Swimming was not a priority for me,” Luis said.

Valentina, too, was absorbed in her education and career. “I miss the feeling you have when you're competing, especially when you are at your peak,” she said. “It's the feeling of being powerful. You'll never be in better shape.”

They've watched the sport change over the years - some of it for the better, some not so much. They especially are disappointed that most of the top competitors are now professionals whose careers are fueled by high-dollar endorsements. While this increases the quality of the athlete, Luis said, it decreases how many prioritize the Olympics.

“Through all those years of training, I always thought that that my work and effort was more special because the reward was not money, but being able to improve myself as an athlete and eventually have the privilege of competing in the Olympics,” Valentina said.

A highly publicized aspect of this year's Olympics that many would see as negative is the housing choice of the U.S. Olympic basketball team. Its members, mostly millionaire professional superstars, are using a chartered luxury yacht complete with pool, wrap-around deck and a cigar lounge.

“The fondest memories I have from the Olympics are sharing time with other athletes and life in the Olympic Village,” Luis said of the traditional housing for thousands of competitors. “You got to meet people from all over the world.”

In the 80s, many Olympic swimmers also went to school or worked jobs that weren't connected to their sport, Luis said. That's not so today with professional Olympic athletes, who earn their living from their sport.

That's brought about differences in athletes' training, Valentina said. “They're not swimming as many hours as we used to. It's more specialized training,” she said. “It's a great improvement so far as it being mentally exhausting like it used to be. The swimmers look less built than in the 80s and 90s. They have a different body structure now because they have less muscle mass.”

When she swam in the early 1980s, Valentina said, “there was a group of swimmers in their early teens setting world records. Now, they're swimming to an older age, and part of that is the training. It takes less of a toll on your body and mind.”

Luis and Valentina Juncos passed on the legacy of swimming to their two children, who are now grown.

Nico, 22, and Natalie, 25, “were quite good swimmers, but they enjoyed soccer much more,” Luis said. “I encouraged them to be soccer players. I just wanted them to be healthy, and to do what they loved doing. If you're not doing what you love doing, you're wasting your time.”

Nico started all four years as a soccer player and served as team captain at Lyon College in Batesville, Ark., where he is completing his degree.

Natalie is a professional soccer player in Argentina, where her club recently won the national championship and is headed to Brazil in December to play in the South American Championship. Natalie played for both the University of Florida and the University of Houston, graduating from the University of Houston with a double major in kinesiology and health sciences. Natalie plans to pursue a degree in physical therapy.

Valentina can be found several times a week in the pool of the couple's Reservoir-area home, and her daily exercise regimen includes weight training. “Working out is part of my life. It's almost like sleeping and eating,” she said.

“When you are an athlete, you have to go through a certain workout, and a coach tells you what to do, and when you're done. Now I can create my own workout and be done whenever I want.”

As for Luis?

He's only an occasional swimmer, but is considering putting in some laps as a complement to his exercise regimen.

“I should, for my health,” he said of getting back in the water. “I clean the pool for Valentina.”