SOD alumna, high school classmates tell desegregation story

Published in News Stories on August 08, 2016

It was January 21, 1970, when the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals finally tired of the city of Jackson dragging its feet with desegregation. Jackson Public Schools were given 10 days to adjust the ratio of black and white students in each school to mirror the ratio in the population of each district.

Children, both black and white, were uprooted from their familiar surroundings and forced to attend strange schools in strange neighborhoods, giving up family legacies and sports glories to participate in a social experiment on a grand scale.

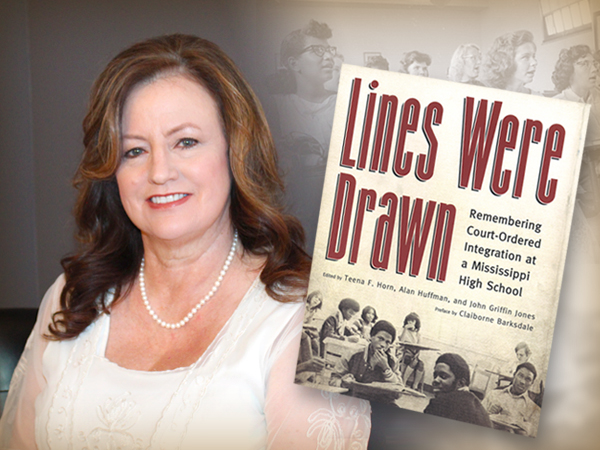

Dr. Teena Freeman Horn, a 1983 graduate of the University of Mississippi School of Dentistry, experienced this disruption first-hand as a student of Murrah High School, located just across Woodrow Wilson from the Medical Center campus.

Horn now runs a private dental practice in Houston, Mississippi.

“I think I was changed by my experiences during that time,” Horn said. “I think that has helped me in my practice. I treat all races. I see physically disabled patients. We don't discriminate, and I don't think twice about that. It changed my view of the world.” Horn said that the lessons she learned at Murrah were reinforced in dental school by Dr. Bill Alexander's classes on community and oral health.

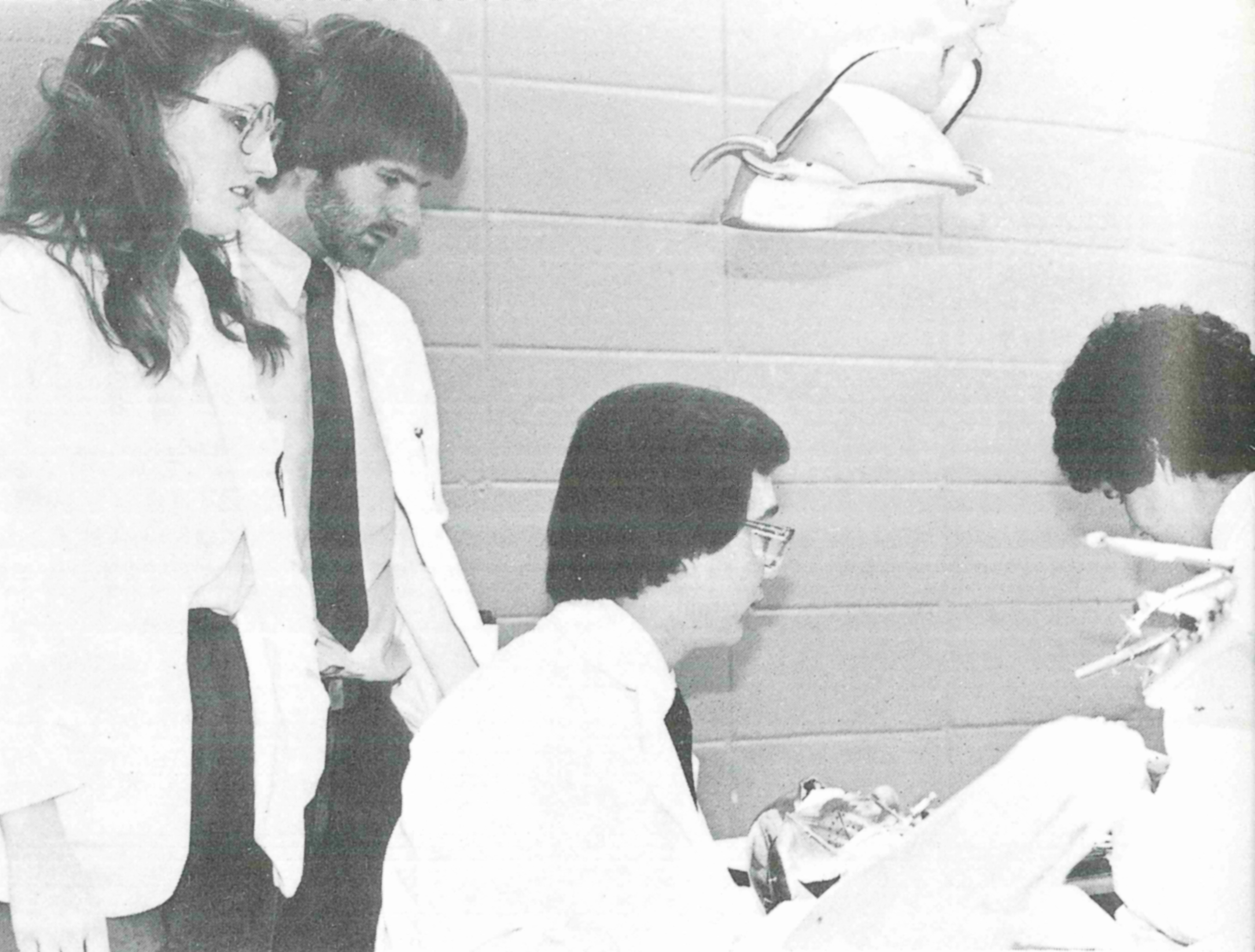

Horn, left, takes part in a community development morning at the SOD in 1981.

Because of how these experiences changed their lives, Horn and fellow Murrah Class of 1973 graduates John Griffin Jones and Alan Huffman decided the stories of their own experiences and those of their classmates must be recorded for history. Those stories are told with many voices in the book Lines Were Drawn: Remembering Court-Ordered Integration at a Mississippi High School, published by University Press of Mississippi.

“We wrote the book because we felt like it was a moment in history that needed to be catalogued,” Horn said. “In fact, a couple of people who are in the book are now deceased.”

The project was born from an email Jones, an attorney in Jackson, sent in 2009 to the Murrah High School Class of 1973, after reading about a Supreme Court opinion in a case from Seattle. The opinion of Chief Justice John G. Roberts was that the 1954 decision of Brown v. Board of Education, which led to desegregation, was no longer relevant today. Having lived through the era of forced desegregation, Jones took affront to the idea that his and his classmates' suffering (and prevailing) was for naught.

Jones's email began by saying, “With the stroke of a Republican pen, this Court abandoned the basic principle that dominated our youth and determined our experiences: desegregation of the public schools was mandated by the Constitution…”

Horn was a Murrah High School cheerleader.

Horn received that email and was offended by the opening statement.

“He said something about the Republicans. I'm a Republican, and he's a Democrat,” Horn said. “We got into a little spat.”

Horn said Jones suggested they write down and share with each other what each of their personal experiences were between forced desegregation in 1970 and graduation in 1973.

“After we wrote our stories, we decided to bring in some other people,” Horn said. “Johnny and I really didn't know what everyone in our class felt about what went on and which schools they went to.”

Two of those other voices were Huffman, now an author, and Claiborne Barksdale, who had been the students' English teacher at Murrah. Horn then placed ads in local newspapers asking for alumni, classes of 1972-75, to contact her to contribute their stories.

“Some people wrote and sent in their stories, and we did some interviews,” Horn said. “You'll see that Governor William Winter was interviewed. His daughter Lele was one of our classmates.” Horn said the group collected 63 stories.

Although the authors sought input from both black and white classmates, the majority of those who replied were white. For this reason, Huffman said in the forward of the book, the story isn't complete. Those who did respond were given an opportunity to tell their stories as remembered with no editing to sugarcoat a difficult subject.

Horn remembers that some students went to two or three different schools, just in ninth grade, as lines were drawn and redrawn by the courts to correct the percentages of whites and blacks in each school. These frequently changing school zone lines drawn on maps of the city and published in The Clarion-Ledger were the inspiration for the book's title.

Horn said she thinks she was changed as a person by what she experienced.

“We had a great group of people and made great friendships that have lasted a lifetime,” Horn said. “We had a lot of professionals come out of that class from Murrah. We learned to look deeper into people. I think that has helped me in my practice.”

Photos

| Population Health Science The Department of Population Health Science was approved as an academic unit in April 2016. Departmental operations will begin in January 2018. Continue to check this website for more information. High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |

| Donate to the School of Population Health Thank you for your contribution to help fund the School of Population Health. Your generous assistance is greatly appreciated! High Resolution Medium Resolution Low Resolution |