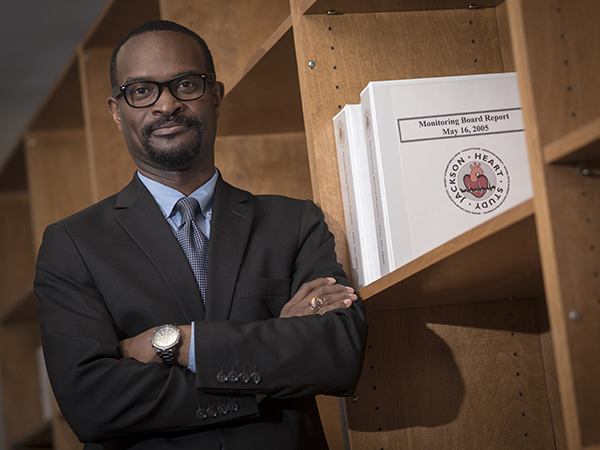

Jackson Heart Study names Sims chief science officer

Published in News Stories on April 27, 2017

If human health is a puzzle to be solved, then Dr. Mario Sims is putting the pieces together as the new chief science officer of the Jackson Heart Study.

“I've always been fascinated by the process of teasing out and dismantling the social determinants of health,” said Sims, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

The JHS is a community-based prospective cohort study of cardiovascular disease in more than 5,000 African-Americans in Hinds, Madison and Rankin counties. Initiated in 2000, the study is a partnership between UMMC, Jackson State University and Tougaloo College. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities fund the study.

Sims will work with the JHS director to promote research collaborations, mentorship and scientific productivity.

A population health scientist and medical sociologist by training, Sims studies the “social factors that impact health and disease,” he said.

While clinicians measure weight or blood pressure to determine disease risk, these aren't the only factors that influence health. Medical sociologists consider other factors, such as socioeconomic status and neighborhood.

Sims gave an example. You're prescribed an antihypertensive drug. If taken as directed, it will control your blood pressure. But sometimes popping a pill isn't as easy as it seems. You may not be able to afford the medication. Maybe the pharmacy is too far from your home or you can't walk there safely. Perhaps a neighbor had an adverse reaction to the medication, so they discourage you from taking it.

“Poverty, neighborhood safety, social structures…these kinds of factors influence behavior,” Sims said, and in turn impact health. When members of a subgroup face similar barriers to health compared to other subgroups, poor health outcomes likely contribute to widening health inequalities.

Correa

“The excess burden of cardiovascular disease among African-Americans has been explained in part by well-known risk factors,” said Dr. Adolfo Correa, director of the JHS. “One of the goals of the JHS is to identify the role of traditional risk factors as well as additional contributions of genetic, environmental, social and cultural factors to that burden.”

Since his recruitment by former director Dr. Herman Taylor in 2003, Sims has developed a reputation as an “excellent” and “productive” researcher, leader and mentor, Correa said.

For example, Sims co-authored a January 2017 study tying higher social cohesion, a measure of trust and relationship among neighbors, to decreased rates of type 2 diabetes. Proximity to convenience stores or similar shops increased the prevalence of diabetes.

That same month, Sims served as guest editor for the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, which included more of his work on the social determinants of health. One study in the issue co-authored by Sims found a connection between cynicism, stress levels and unhealthy behaviors; another tied perceived discrimination to obesity risk.

However, there's a blind spot on the road connecting physiological health and the psychological and social environment: the starting point. Many studies can show correlation, but not causality, Sims said. Someone might be stressed because of their kidney disease, or the stress in their life might trigger an inflammatory response that makes them more susceptible to kidney disease. Or the road is a two-way street, creating a feedback loop.

By using the Jackson Heart Study's seventeen and counting years of data, Sims thinks they can start to tease apart the relationship to find out which comes first.

“We want to find the underlying mechanisms,” Sims said.

Sims mentors La'Shaunta' Glover, a JHS graduate research assistant.

Another of Sims' goals as chief science officer is to “develop a pipeline for African-Americans in biomedical sciences” through mentorship, he said during a December 2016 town hall presentation.

He hopes to instill in his mentees a sense of accountability and confidence in their ability to do good work, while steering them towards fruitful projects.

Sims earned a bachelor's degree at the University of California-Los Angeles, a master's and Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and conducted postdoctoral work at the University of Michigan, Medical College of Wisconsin and UMMC. He credits mentors from all of these institutions for building his interest in population health and health disparities.

W.E.B. Du Bois probably deserves some credit as well. While at UCLA, Sims read a case study by the noted scholar based in an 1890's Philadelphia, Pennsylvania neighborhood.

“It's considered the first study of an urban population of African-Americans,” Sims said. “He documented everything they experienced,” from poverty to demography to infectious disease. Du Bois tied the relatively poor health status of the residents, even those with higher income or social status, to discriminatory practices, Sims said.

More than a century later, Sims sees in Jackson what Du Bois saw in Philadelphia.

“A lot of these things haven't changed,” Sims said. “Now, we see chronic diseases [such as hypertension and diabetes] but the same social determinants of health still stand. We still have work to do.”

The JHS is a critical part of that work, and it wouldn't be possible without thousands of study participants from the Jackson area.

“I see myself as a voice for translating the research findings [for the community],” Sims said, which requires “listening and learning how to be a better steward of the data for our community partners.”

“With [Dr. Sims'] expertise, the Jackson Heart Study is poised to address important knowledge gaps on social determinants of health inequities in cardiovascular disease among African-Americans,” Correa said.