With Homerun Project, it’s a brand-new ballgame for science teachers

Key points:

Teach students the value of making healthy choices

Teach students the consequences of making poor health choices

Teach students where to search for valid health information

Teach students to set high health goals for themselves

Teach students to advocate for the health of themselves and others

Source: Homerun Project, information for medical students

This is a story about potato chips, candy, a sock and a golf ball – and how they can make a kid into a scientist.

Peggy Carlisle’s fourth-grade science students were exploring the senses of touch, taste and smell; but their sense of curiosity was the sharpest of all.

“I have a question: I have a thing on my hand and it won’t go away.” “What do you do for a sore throat?” “If you have an ‘M’ on your hand (palm), does that mean you’re going to get married?”

Even these off-topic concerns of Carlisle’s Pecan Park Elementary School students were patiently addressed by Mikey Arceo and Turner Brown, two second-year medical students from the University of Mississippi Medical Center who were their visiting teachers: “It’ll go away.” “Gargle with salt water.” “I have two ‘Ms’ – does that mean I’ll be married twice?”

A partnership between UMMC and the Mississippi Department of Education’s Office of Healthy Schools, Homerun has scored at three separate Jackson Public Schools sites, putting medical students in several of their classrooms over the past three years.

For the future doctors, participation in Homerun is a way to fulfill their community service obligations.

“At UMMC we have an army of volunteers than can offer this service,” said Dr. Rick deShazo, UMMC distinguished professor of medicine, pediatrics and immunology, who helped launch Homerun.

This kind of work also satisfies the altruistic impulse that inspired many students to become physicians in the first place, he said.

It also gives them a taste of their future role as educators for their patients, and helps them learn how to communicate with children.

Another perk: Often, they are inspired by their young audience’s keenness and insight.

When Arceo told Carlisle’s class he plans to become an ENT, one boy asked, “Does that mean you’ll be messing with tonsils and adenoids?”

Yes, it does. And if the Homerun Project realizes another of its goals, maybe that inquiring fourth-grader will grow up and mess with them, too. Or maybe he’ll become an R.N., an O.T., a P.T., scientist, surgeon, and so on.

“Interest in a science-based career has to be sparked by the fifth grade,” said Carlisle, who should know; she is also the pre-school/elementary division director for the National Science Teachers Association.

In other words, the medical students, with their fresh faces and fresh perspectives, serve as role models – and in more ways than one. They are also proselytizers for wholesome habits.

“The students they teach learn about healthy eating, the importance of normal weight, that fast food is problematic because of the calories,” deShazo said.

The idea for Homerun got to first base a few years after the 2007 passage of the Mississippi Healthy Students Act, which mandates more physical activity and health education for students.

But without state funding to back the act, the Department of Education searched for creative ways to make that happen. The Homerun Project became one of those ways, beginning with a pilot program in 2011 at Jim Hill High School in Jackson.

“Some M3s brought in some human kidneys to the class,” said Susan Bender, chairman of Jim Hill’s science department. “That was a tremendous hit.

“I honestly think the medical students get as much out of it as the students they teach. It doesn’t hurt that they bring candy or some other bribe to pass out when they’re finished.

“But I believe it’s been a humbling experience for some of them as well. If high school students don’t understand what you’re talking about, they will tell you quickly.”

“I found it incredible how the health sciences world is finding various cures. I learned a lot that I didn’t know. The medical students seemed to really know what they were talking about.”

The pilot at Jim Hill took off. And now the ultimate goal is to take the program statewide.

In 2012, the Department of Education added JPS’ Pecan Park and Davis Magnet Elementary schools to the lineup, said Kevin Batte, the UMMC student representative for the program.

“The idea was to reach students at an even earlier age.”

Arceo and Turner tried to reach Carlisle’s students with, among other things, an athletic bag, a red sock and a mysterious object.

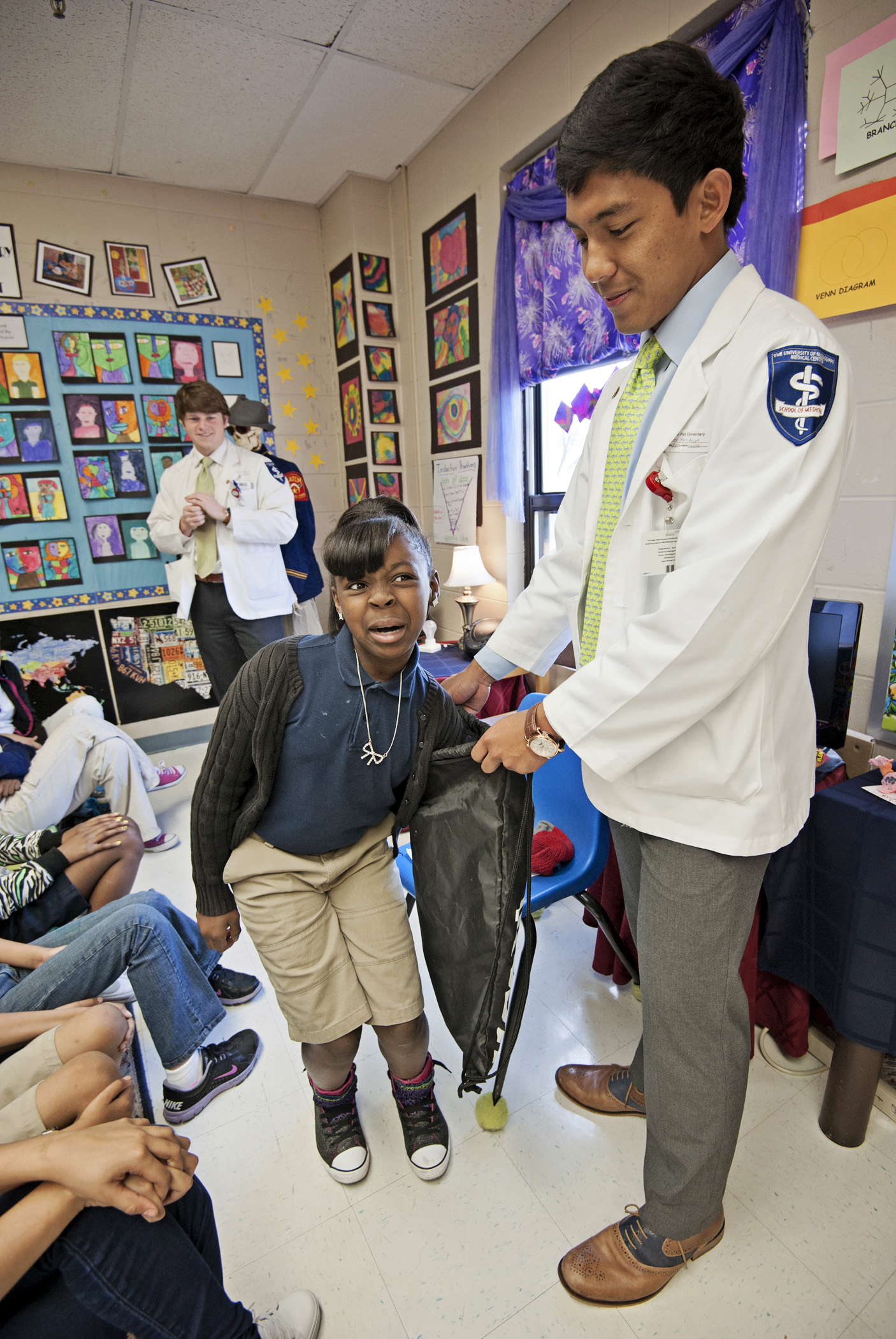

Alondria Taylor was the guinea pig: With her right hand, which was covered by the sock, she rummaged inside the bag, found the object and used her sense of touch to identify it as some kind of ball. But it wasn’t until she felt it with her bare left hand that she could discern the dimples and nail it down: “Golf ball,” she said.

This kind of demonstration is bound to appeal to younger students. “The younger the better,” said Christine Philley, the school health administrator for the Office of Healthy Schools.

“I don’t know of any other program like Homerun in our state right now,” Philley said. “We’d love to have more.

They’d also like to find more donors, in addition to such benefactors as the Selby and Richard McRae Foundation, to pick up some costs or offer in-kind giving.

If funds are hard to come by, though, there is no lack of commitment.

“All the partners are passionate about teaching a lesson that has value,” Philley said. “The teachers who invite the medical students really want what’s best for their kids.”

Those teachers choose the topics, which have included the pros and cons of vaccinations, and polio – then and now. Their choices are passed on to the medical students by Dr. Jerry Clark, UMMC chief student affairs officer and associate dean for Student Affairs in the School of Medicine.

Arceo and Turner passed out Warheads sour candy to Carlisle’s fourth-graders, along with Pringles potato chips and other snacks for consumption, asking the students to note how different parts of the tongue enhanced the various flavors – salty, sweet, sour, bitter – according to the location of specialized taste buds.

“Taste buds?” said one student. “My mom told me those are ‘lie bumps.’”

Be that as it may, one of the day’s lessons was that the senses of taste and smell are closely related and “help build memories,” as Turner put it.

“They help make us who we are.”

And that’s how it’s done.