UMMC researcher’s pioneering work gives rise to new severe depression drug

It was 1989, the year the Nintendo Game Boy was released, and the year a young scientist named Dr. Ian Paul and some of his best friends began researching what would become one of the world’s most promising new treatments for severe depression.

His research group was the first to hypothesize that major depression has a connection with the brain neurotransmitter glutamate, and that drugs that block glutamate receptors would have an anti-depressive effect.

Their research using dizocilpine and a half-dozen other drugs supported it; their work was further validated in 2000, when a group of researchers at Yale University built on it by using the anesthesia drug ketamine to successfully block glutamate receptors.

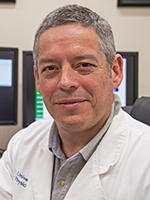

“We argued for 10 years that these drugs had major potential because they worked extremely rapidly, and because they were very, very potent,” said Paul, professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, who has devoted much of his life’s work to understanding depression, what triggers it, and what gives relief.

On March 5, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the nasal spray formation of esketamine, a purified version of the drug ketamine, for use in severely depressed adults who have tried other antidepressants with no success. Ketamine was approved as an anesthesia drug for human use in 1970.

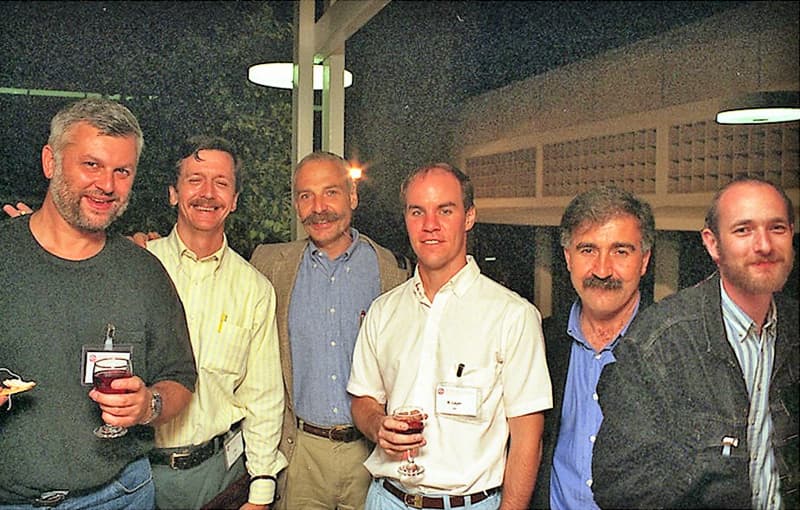

“About half a dozen of us worked on this project for years and years and years,” Paul said. “We had an email party last week about it, slapping each other on the back.”

Esketamine is being hailed as the first truly new kind of depression drug in 30 years. It works through a totally different mechanism than any other FDA-approved treatment, which researchers say might be the reason it helps people who haven’t been helped by other drugs.

One of esketamine’s attractions is that it can get results in just hours in part because it’s inhaled or given via IV, allowing it to get to the brain quickly and start working faster. The exact reason for that isn’t entirely clear.

Traditional antidepressants taken by mouth “take between four and six weeks to work, if they work,” Paul said. “They don’t work in about 30-35 percent of people treated, although for reasons we don’t understand, if you switch among the existing antidepressant drugs, you can get success closer to 75 percent of the time.

“The problem is, four to six weeks is a long time to wait for a patient who is at high risk of self-injury or not functioning well,” he said. “If you have to switch drugs or increase the dose, you are looking at six or eight or 10 weeks. You are working with a group of patients who often have characteristic feelings of hopelessness. If the drug doesn’t work quickly, they will assume that nothing is going to work.”

Esketamine is self-administered by the patient as an inhalant only in an approved physician’s office, under close supervision, esketamine is expensive. The recommended course of treatment is twice weekly for a month, then weekly or biweekly after that. Generic ketamine that is FDA-approved as an anesthetic and pain reliever has been available for some years at clinics that have sprung up around the country. Those clinics administer ketamine through IV infusion, sometimes as off-label treatment for depression.

Paul’s research team included Dr. Phil Skolnick, a researcher with the National Institutes of Health, now chief scientific officer with Opiant Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Ramon Trullas, now a scientist with the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) in Barcelona, Spain; Dr. Gabriel Nowak and Dr. Piotr Popik, scientists with the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow; and Dr. Rick Layer, vice president of research at InVivo Therapeutics in Boston.

The FDA’s approval comes almost 30 years to the day of the publication of a 1989 paper written by Trullas and Skolnick, as lead discoverers, about the group’s research at the Laboratory of Neuroscience at the NIH and the findings.

Dr. Allen Richert, associate professor of psychiatry, agrees with Paul that esketamine could be a game-changer. “The reports are that the response can be very dramatic – a patient going from the depths of despair to feeling like they’re just a normal, everyday person,” Richert said. “It’s not a feeling like you just won the lottery, but a normal, everyday good mood within a matter of hours.

“I’m a little skeptical myself. I want to see it happen,” he said. “But what’s exciting is that it really does seem to help with mood, even if it’s not dramatic, and that it seems to be doing it through a completely novel approach to the neurochemistry of the brain.”

UMMC physicians likely will begin administering esketamine for severe depression in coming months, Paul and Richert said. “It’s possible that esketamine combined with traditional antidepressants might help them to work faster. That’s a guess at this point,” Paul said.

Paul is working with Richert and Dr. Sara Gleason, associate professor of psychiatry, to develop an interventional psychiatry unit that will use ketamine drugs as antidepressants, with plans to conduct clinical trials on their potential value in treating post-traumatic stress disorder.

Esketamine “is not going to be a panacea for depression,” Richert said. “It’s not going to cure everyone, but it’s a game-changer, and it gives us new tools to treat this. People will want to give this a try.”

“There’s nothing more gratifying for a biomedical scientist than to see an idea they worked on so hard make it into the clinic to help people,” Paul said.