Rare procedure splits donor liver between two women

Published in News Stories on April 13, 2017

When Roda Barnes met a new friend Monday at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, she invited her into her room on the hospital floor reserved for transplant patients.

“Come on in, Roda!” Barnes said.

She wasn't talking to herself. Barnes not three minutes earlier had embraced Bettina Dixon, a woman half her age whose abdomen now cradles the other half of the donor liver that Barnes received. On April 3, the women shared the organ in a very rare split-liver surgery performed by Dr. Christopher Anderson and Dr. Mark Earl.

Neither woman had set eyes on each other, had shared stories or hugs or sheer joy with each other, until a week after their surgery, when Dixon walked three doors down the hall to Barnes' room.

“I've been wondering about you this whole time,” Barnes, a 46-year-old medical laboratory worker from Vicksburg, told Dixon, 22, a Byram resident and student at Jones County Junior College.

“You look really good,” Barnes told Dixon. “You do, too,” said Dixon, who proclaimed them “sisters for life.”

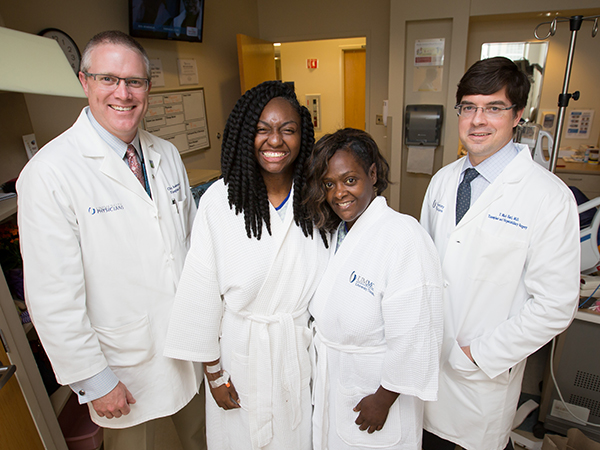

Barnes, left, and Dixon meet for the first time during their recovery.

So many things had to come together for the women to undergo a surgery almost always reserved for an adult sharing a small portion of a donated liver with a child or baby. Each personally had to be a match. The two recipients had to be of similar build and weight. Their anatomies, and that of the donor, had to be very similar. And, the vascular anatomy of the donated liver had to be conducive to a split.

“Splitting a liver is very difficult to do,” said Anderson, professor and chair of the Department of Surgery and chief of the Division of Transplant and Hepatobiliary Surgery. Hepatobiliary surgeries concern the liver, gallbladder, bile ducts or bile. “There are a lot of logistical challenges, not to mention technical difficulties. You have to have recipients that are the adequate size for that amount of liver.”

Anderson and Earl, associate professor of transplant surgery and general surgery program director, did a good number of pediatric-adult liver splits before coming to UMMC. The Medical Center has active pediatric heart and kidney transplant programs, but not pediatric liver.

This was the first split between two adults performed by Anderson and Earl. “The overwhelming majority of transplant centers in the United States have not done it at all,” Earl said.

The adult split is so rare that in 2016, only five were performed in the United States, representing 0.01 percent of all liver transplants that year, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, the national governing body for organ transplantation. In 2015, it was four; in 2014, just three.

From 1988-2016, UNOS says, there were 93 livers split between two adults. That compares to 1,315 livers split between an adult and a child, and 159 livers split between two children, over that same time period. UNOS defines a pediatric patient as age 0 through 17.

Stump

Mississippi Organ Recovery Agency president and CEO Kevin Stump said it's the first liver split between two adults that he's seen since entering his profession in 1986. He has been involved in the allocations of three other livers that were split, all between two children.

“This is extremely rare, and speaks highly to the excellent transplant program created at UMMC,” Stump said. “When I heard about it, I was like, 'They did what? Cool!'”

Although their diseases encompassed a year or more, the women's journey from transplant waiting list to surgery was swift. Each had been on the list for no more than a couple of weeks when they were summoned with a phone call to the Medical Center in the wee morning hours of April 3.

The transplant put an end to Dixon's fatigue, breathlessness, bloating and body fluids literally draining from her legs due to edema caused by her failing liver. It started about the time of Easter 2016, when she came home from working a shift at McDonald's. “I was sluggish and could barely walk,” Dixon said.

It was the same the next day. She went to a walk-in clinic in Laurel. Staff gave her a steroid shot. But when she went back to work, “I felt something leaking out of my legs. I thought I had stepped in water or oil,” she said.

That Sunday, she told her mom, Chauncenia Jackson: “Don't ask me to cover the door at church. I can't do it,” Dixon said. “Then I raised up the skirt of my maxi dress, and showed her the leaking.”

At Jackson's urging, Dixon went back to the clinic in Laurel the next day, then to the ER. Her diagnosis: an autoimmune disorder causing cirrhosis and liver failure. She was sent to UMMC to see Dr. Brian Borg, associate professor of digestive disorders and a transplant hepatologist. “They said she had to have a transplant. She was too far gone,” Jackson said.

Barnes found out in February 2014, when she was living in Michigan, that she had primary sclerosing cholangitis, a disease in which patients develop progressive biliary strictures throughout the biliary tree of the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts that leads to cirrhosis and other complications. “I was in my lab, and I looked at my liver enzymes and saw that they were off,” Barnes said. Her disease was discovered when she had gall bladder surgery, she said.

In May 2015, she took a medical laboratory job in Vicksburg, near relatives in Port Gibson and Pearl. She became jaundiced, tired and sleepy. “I knew a transplant was coming. I didn't think it would happen in Mississippi,” she said. Her gastrointestinal specialist in Vicksburg sent her to Borg.

“They called me at about 12:45 on April 3,” Barnes remembered. “I was in complete shock. I sat on the bed and cried and prayed. I didn't think I was ready. It took a while to soak in.”

“Mama, it's the liver people!” Dixon remembered telling Jackson when their call came. “They want me to come now! I'm so excited!”

“The doctor said it was a perfect liver, and that he wanted to share it,” Jackson said. “The human body is amazing.”

“You've got a liver that's available, and we knew that it was potentially splittable,” Earl said. “I called Dr. Anderson and said, 'Are we crazy?'”

They were not.

“It's the right thing to do. We went through all the steps to estimate liver volumes and to check donor anatomy before we proceeded,” Anderson said. “We did all the calculations, and everything seemed to be fine.”

Anderson and Earl operated that night with double the regular OR transplant team. No one hesitated to come in when they weren't scheduled to work. “If you're not at a center that has a team that rises to the challenge, you can't do this,” Anderson said.

But if anything along the way rules out splitting the donor liver, Earl said, the patient whose case is most dire according to a national scale set by the United Network for Organ Sharing will get the entire liver. “That decision is made for you,” he said. “If the liver is not suitable for splitting, then the patient highest on the list receives the whole organ.”

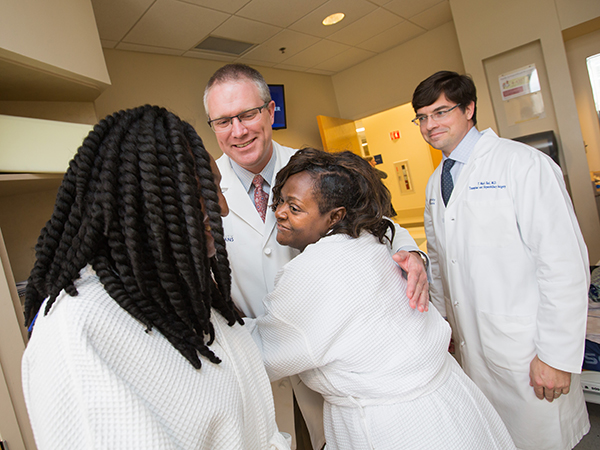

While Dixon and Earl watch, Anderson shares a hug with Barnes.

Just hours after meeting for the first time, both women returned home with orders to rest and adjust to medications they'll take for the rest of their lives to keep from rejecting their organ.

“They're doing better than we ever could have dreamed,” Earl said. “It's high risk, high reward. They're going home after a week. Their livers will regenerate, and as they grow, the function will completely normalize.”

As their livers expand, so will the friendship between Dixon and Barnes.

“It's awesome,” Dixon said. “I'm very blessed she has the same liver. This is coming from my heart. I'm so happy she has the other part.”

“We're sharing this organ,” Barnes said. “She's stuck with me.”