Asylum Hill grant boosts mission to record descendants’ stories

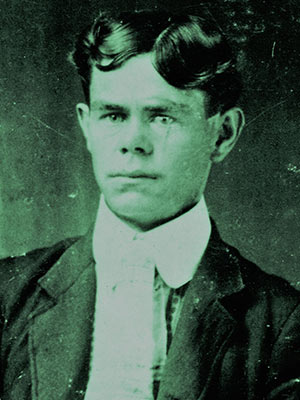

“King Cotton” lured John Benedict Whitfill from his life in Kentucky to the place he would die.

During the hard times of the Great Depression, he hauled his family and furniture in a Chevy truck to Mississippi, moving eventually to the Delta, where he expected to reap promised riches wrapped in cotton.

Instead, he harvested misery and malnutrition and a disease that put him in the Mississippi State Hospital for the Insane; there, he became one of the many nearly-forgotten patients buried on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, once occupied by the asylum that vanished like Whitfill’s dream.

Now, bolstered by a recently-awarded federal grant, the partners of the Asylum Hill Project, led by UMMC, are recovering those patients’ stories – for the sake of history and their descendants, including Whitfill’s grandson.

“For a long time, we didn’t know what had happened to our grandad,” said James T. Lee of Owensboro, Kentucky. “We had tried to find his body; our intention, at first, was to have him moved back to Kentucky, to the grave beside my grandmother.”

As participants in the oral history drive supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Lee and his brother Wayne Lee of Durham, North Carolina, have agreed to tell what they know about their grandfather.

The title of the undertaking, “Finding Community: Documenting Descendants of Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum Patients in History and Cultural Memory,” refers to the original name of the institution which operated from 1855 until 1935 – that is, until about three years after Whitfill’s death.

NEH’s $11,993 Common Heritage Grant is helping pay for, among other things, video recording equipment, scanners to reproduce historical documents and publicity to encourage descendants to weigh in.

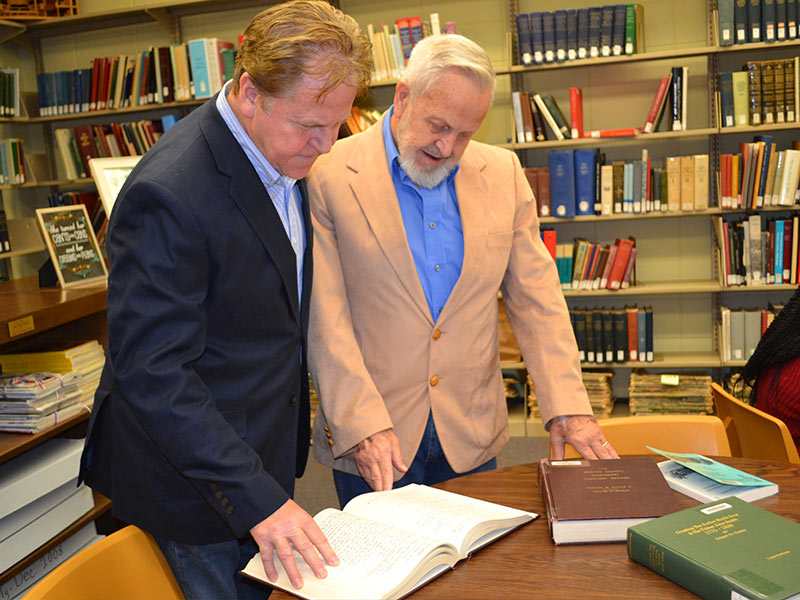

“Community engagement is critical,” said Dr. Ralph Didlake, UMMC associate vice chancellor for academic affairs and chief academic officer, who assembled a band of experts and scholars to form the Asylum Hill Research Consortium.

The consortium has applied for another, larger NEH grant that could come through later this year, one that would fund the creation of a database and more information-gathering.

“Any money is big money in the humanities world,” said Didlake, who also directs the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities, one of six consortium members representing the Medical Center.

“This grant is fabulous for the Asylum Hill Project.”

That venture is the province of the consortium formed to preserve and promote the asylum’s history. Made up primarily of many of Mississippi’s public universities and several community partners, privately-supported Millsaps College in Jackson has been a vital member as well.

It was Dr. Amy Forbes, Millsaps associate professor of history, who helped open the door for the grant.

“This all started with Amy,” Didlake said. “She led the way.”

Among the pages of the asylum’s official history, there is a “gap” that needs to be filled, said Forbes, who is also assistant director of archival material management with the Center for Bioethics and a UMMC associate professor for academic information services.

“Because the asylum closed in 1935, it’s unlikely we will talk to anyone with direct information about it, but descendants can tell us what they know from family lore and what it meant to them; they can help explain the asylum’s place in the state’s history.

“People seem to be eager to tell their stories. They’re curious about their ancestors. We need to reach them in every way we can. They want to get information and they want to share their information with us.”

Many will have the chance to do that on two as-yet-undetermined dates this summer, when project participants will play host to a gathering of descendants to collect their histories, letters and other documents at Jackson State University’s Margaret Walker Center, another consortium member.

Several Millsaps students trained to take oral histories will be on hand.

Patients’ relatives may also contribute to, or pull information from, the Asylum Hill website managed by Lida Gibson, the assessment and research coordinator who is coordinating the oral history mission for UMMC.

“Between the descendants’ stories, asylum records, newspaper clippings and ancestry.com, it’s amazing what a detailed portrait we can put together of these patients who were often marginalized when they were alive,” Gibson said.

Already, she said, dozens of descendants have shown interest in this endeavor, including Lee, whose grandfather’s last name is also listed on some records as “Whitfield” – coincidentally, the name of a Rankin County town about 12 miles from Jackson; it is the home of Mississippi State Hospital: the asylum’s successor.

In the late 1920’s, John Whitfill, or Whitfield, and his family were living in western Kentucky, near a community whose name may have been inspired by a local asphalt mine and quarry: Tar Hill. The family tapped maple trees to make syrup and sugar Whitfill sold at nearby Leitchfield.

“They also raised corn, and they had a garden and a cow and, I guess, a hog and chickens,” said Lee, who learned all this from his mother.

“My grandad would hang out at the railroad depot to watch the trains and read the farmers’ magazines there. One of them talked about ‘King Cotton’ and how much money you could make from it in Mississippi. That’s why he decided to go there.”

The family lingered a while in Tupelo before heading west to settle in Leflore County, near Itta Bena. That’s where Whitfill’s dad – Lee’s great-grandad – died and was buried, having moved there from Kentucky after his son sent for him.

“Times were bad and they were starving,” Lee said. “My granddad was worried about the kids; they came first, as far as getting to eat. So he ended up having pellagra.”

A vitamin deficiency resulting from malnutrition, pellagra can lead to delirium. “My grandad would say there were people outside who were coming to get him,” Lee said. “He was losing his mind.”

It appears that someone contacted the sheriff, Lee said. But Lee’s grandmother couldn’t read or write, so the oldest child had to sign the papers committing John Whitfill to the asylum: Lee’s mother.

“That always bothered her,” Lee said.

Whitfill entered the hospital in November and died about two months later, on Jan. 3, 1932. He was 56.

Over the years, Lee and his relatives tried to find out more about John Whitfill’s death. “We went to Whitfield around 1978 or so, because that’s where we thought he had been,” Lee said. “But the people there said they didn’t know where he was buried or what had happened to him.

“So I sent off for his death certificate. It said he died of pellagra. He was probably one of the last ones buried there in Jackson.”

By early 2013, a road construction project on the Medical Center’s northeast campus had uncovered dozens of coffins that turned out to hold the remains of asylum residents. Later, a geophysical survey revealed that many more coffins lie underground and unmarked across some 20 acres of UMMC, which opened in 1955, 20 years after the asylum closed in Jackson.

The discovery of the graves led to the creation of the Asylum Hill Project, an initiative with many parts, including plans to place patient remains in UMMC’s Farmer’s Market facility, reclaim the burial sites for future land development, build a memorial to the patients and establish a field school with a long-term scientific and educational program.

Archaeologists believe that the remains of as many as 7,000 asylum residents are still buried on the Medical Center’s campus. The death certificates of more than 4,000 of these patients can be viewed online through a search engine provided by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History’s website.

Many, succumbed, officially, to pellagra, like Lee’s ancestor. Identifying him, or any one of the thousands of people buried near the former asylum site, would be difficult – something Lee has grown to realize.

As Didlake has pointed out before, the extent of the cemetery is still unknown; construction may have obscured some of the gravesites, so not everyone may be exhumed, although plans are to disinter as many as possible.

“We wanted to move my grandad back to Kentucky,” Lee said, “but I don’t know if we could ever say for sure we can find him.”

For now, he and his family’s best hope is that his remains, like thousands of others, will be reburied and placed near the memorial.

“At least we would know he’s there. Maybe his name would be there somewhere, too.”

To participate in the Asylum Hill Project, contact Lida Gibson at lbgibson@umc.edu.