‘A caring situation’ Students of the Jackson Free Clinic show up where the people are

Note: This article was originally published in the Winter 2024 issue of Mississippi Medicine, the medical alumni magazine.

On a sunbaked weekday last fall, students from the Jackson Free Clinic were getting warmed up, in more ways than one, at one of the 30 or so service providers’ tables, tents or booths strung along Amite Street.

It was a day of balloons, burgers and blood pressure checks.

The occasion was the World Homeless Day Community Fair in Jackson, conceived to draw attention to the needs of people like Zornia Collier, who approached the JFC students on her walking cane, her possessions stuffed in a blue backpack hugging her shoulders.

She was there for a free glucose check.

“This is definitely great for people like me who can’t afford health care,” said Collier, who has been homeless for six years. “With these students, it’s a caring situation. It’s not for a paycheck. It’s from the heart.”

For the past quarter-century, people like Collier have relied on free, non-emergency health care from the students who run the Jackson Free Clinic.

Increasingly, the students, most of whom attend the University of Mississippi Medical Center, have, gone to this vulnerable population, often through partnerships with community organizations such as Stewpot, Shower Power, We Will Go Ministries, Grace Place and more.

Through this fortified effort to fill a large health care gap in Mississippi, the students are meeting more and more people like the woman medical student Jody Morgan will never forget.

“She always had a hug and a smile for me, even if she was having a bad day,” Morgan said. “And she was usually having a bad day.

“Sometimes, I would ask her, “Did you take your medications?’ And her answer would be, ‘No, baby, I had to buy food.’”

Pressure cooker

At Stewpot Opportunity Center, BSN student Bryce Harrison takes time to get to know Ira Williams of Jackson.

Every Saturday morning, JFC students welcome patients to the medical clinic on Jackson’s Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

Behind the building is a dental clinic, and the students are planning to add another structure dedicated to more health care services.

Beyond the clinic’s confines, JFC students also offer health screenings and more out in the community several times a month, extending their reach not only within the Jackson area, but also to far-flung rural towns.

“For many patients, we are the only place where they get their medical care,” said Morgan, COO, specialty services, for JFC – a separate legal entity supported by UMMC.

These are among the 14% of Mississippians under age 65 who are uninsured, as estimated by the County Health Rankings & Roadmaps program. The rate is four points higher than that for the U.S.

For Hinds County, where Jackson is located, it’s 15%; for some counties, it’s as high as 20.

Many of JFC’s patients are between 30 and 40 years old, Morgan said. “They’re the working poor, including many who don’t qualify for Medicaid.

“Often, they can’t afford health care premiums or day care or food.”

As often as they can, JFC students try to help those who come to them secure an appointment with a local physician; and help them, if they qualify, navigate the path to Medicare or Medicaid.

Many are so busy trying to make a living, they ignore their health far too long, including the man in rural Mississippi whose blood pressure reading was 218 over 184.

“I thought, ‘that can’t be right,’” said medical student Will Jones, who focuses on rural outreach for JFC.

“My own blood pressure went up.”

Where the people are

On World Homeless Day, organized by the Central MS Continuum of Care and Stewpot Community Services, Quinton Sutton also found his way to the JFC students.

Because someone had stolen his car, Sutton had to walk to the event, where he arrived at the table staffed by medical students Camille Couey, Abigail Macoy, Kaitlyn Anderson and Eva Kiparizoska, along with Madeline Manuel, a Health Ambassador from Mississippi State University.

“People should know that these students are here to help you, like the police who are here,” said Sutton, a men’s shelter resident who, at age 25, wrestles with high blood pressure.

“I’m depending on things like this,” he said.

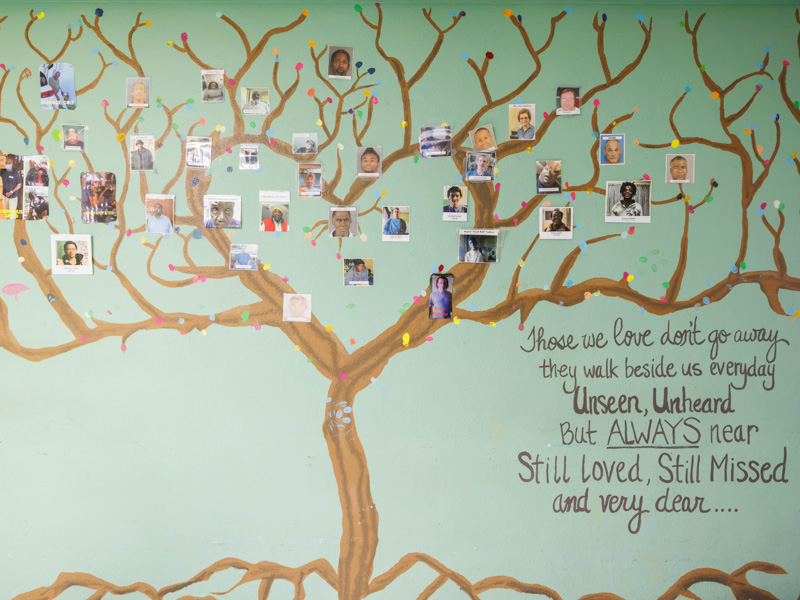

The potential upshot of the health challenges confronting people like Collier and Sutton is literally written on a wall.

At the Stewpot Opportunity Center on Amite Street, a “home base for the homeless” in Jackson, visitors are greeted by a mural of a massive tree sprouting human faces.

One September Saturday morning, visitors included representatives of JFC. Bearing blood pressure cuffs and other health screening aids were nursing students Presley Holloway, Sutton Richmond, Macy Jones, Emma Reinike and Bryce Harrison, and graduate studies student Kaleigh Nathaniel.

If they had examined the mural, they would have noticed that the “leaves” on the tree were snapshots of more than three dozen people Stewpot has ministered to and who have recently died.

“People who live on the street and in shelters don’t have easy access to health screenings and other medical resources,” said another World Homeless Day attendee: the Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot Community Services, a provider of food, shelter, clothing and more to the poor and homeless.

“So, we love our partnership with the Jackson Free Clinic.”

Establishing relationships between academic medical institutions and organizations like Stewpot is the way to go, says the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Center for Health Justice: “Local organizations, which are often closest to their own community’s health challenges, are best positioned to provide effective solutions.”

Those who work with the unhoused say many of them are unaccounted for; if so, this estimate from the National Alliance to End Homelessness is probably low: On a given night in 2023, the latest year for which figures are available, 982 people experienced homelessness in Mississippi; about one-third of those live in the Jackson-area counties of Madison, Rankin and Hinds.

“The Jackson Free Clinic makes it easy for them,” Buckley said. “The students even offer them transportation – which is so important to people always on the move.

“The students show up where the people are.”

Good soil

As an undergraduate, Chris Glasgow volunteered with JFC, intending to pump up his resume and improve his chances of getting into medical school.

“But when I saw what the Jackson Free Clinic was doing, I fell in love with it,” said Glasgow, a fourth-year medical student at UMMC and COO of the clinic’s Operations Board.

“I knew I had found what I wanted to do. To get that feeling of ‘this is why I want to be a doctor.’”

For Jasmine Key, JFC co-director of community outreach, the rewards include grateful gestures from people she tries to help. “This one patient, a guy, gave me an apple,” she said.

“Maybe,” Glasgow responded with a grin, “he thought it would keep you away.”

Still, it takes a “special kind of person” to do the work of the free clinic for free, Morgan said.

“You’re adding 12 to 15 hours to your schedule, including administrative work no one sees. You may wonder at times if it’s worthwhile.

“Until that one patient brings you an apple.”

For their community outreach efforts in 2024, JFC students recorded 76 events, with more than 1,300 people contacted by 400-plus volunteers, said Caroline Doherty, JFC’s chief outreach officer.

The success of JFC is the ultimate expression of Dr. Joyce Olutade’s dream: to fight against health disparities on behalf of the underserved.

“From the beginning, the students took the idea and ran with it,” said Olutade, a family medicine physician and the clinic’s founder.

The beginning was January 2002, when Olutade, the clinic’s first medical director, helped create the non-profit clinic with the aid of a grant.

Today, it offers many more services and many more volunteer hours from students and faculty representing multiple UMMC schools.

It was a natural outgrowth of empathy born of Olutade’s childhood in Nigeria, where civil war deprived people of their homes and lives. Those sights stayed with her as she began her medical career in the U.S.

The apotheosis is the clinic on MLK Drive, which is open every Saturday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.

Supervised by UMMC physicians and residents and doctors from the community, the students have their own governing board.

Besides the medical clinic, there is also now a dental clinic, and many more services, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, vision, gynecology psychiatry and much more.

The number of students involved “is in the hundreds,” Glasgow said.

On top of that, there are undergraduate students from other Mississippi colleges and universities who volunteer through JFC’s Health Ambassador Program.

Olutade likens JFC’s beginnings to the planting of an acorn. “I found Jackson, Mississippi, to be good soil,” she said. “What I see now is a big tree.”

‘A beautiful thing’

Grace Place Ministry, located in the shadow of the State Capitol, had just finished serving breakfast.

The diners were a group of folks described by the Rev. Lori Galambos Till as “unhoused or who are housed and have jobs; but all are tight on their budget.”

A service of Galloway United Methodist Church, Grace Place is another JFC community partner. On certain days, students contribute health screenings and information about healthy eating.

“The more often the students have come here, the more trust they have built with the people who depend on Grace Place,” said Till, Galloway’s pastor to church and society.

A mile south of the church, next to the Commerce Street railroad tracks, Wilbert McGee, a sheetrock hanger with a bad back, was waiting to take a shower.

For the past five years, McGee and scores of other people in need have gathered there every Friday morning at the headquarters for Shower Power, a nonprofit offering free clothing, hygiene items, meals and, in its mobile unit, hot showers.

On this brilliant fall morning, many were visiting the JFC tent, where two medical students – Abigail Macoy and Hannah O’Bryan – were working alongside three MSU Health Ambassadors.

McGee, for one, often depends on JFC health screenings. “I’m a diabetic,” he said. “I have to keep myself checked. I want to make sure I don’t have a stroke.”

Shower Power’s founder, Teresa Renkenberger, has stories about the lives JFC students have helped improve, and probably saved.

“One man’s blood pressure was so high, he had to go to the hospital that day,” she said.

The students at work “is a beautiful thing to watch,” Renkenberger said. “They don’t rush anyone; they take time to talk to everyone.

“The Jackson Free Clinic fits perfectly beside us. We have a saying: ‘We love people back to life and we love them right where they are.’ And that’s what the Jackson Free Clinic does.”