New study: More Americans are giving up on losing weight

As national obesity rates climb, fewer overweight Americans are trying to shed pounds, a new research study shows - perhaps because a heavier weight is becoming socially acceptable.

In Mississippi, where one out of every three people is considered obese and chronic illness is rampant, it's troubling news. Researchers also found that with some people, it's not that they're satisfied with their weight. They've stopped trying after failing over and over again.

When it comes to heavier-weight acceptance and giving up on weight loss, “the second one leads to the first one,” said Dr. Dan Jones, professor and interim chair of the Department of Medicine and director of clinical and population science at the Mississippi Center for Obesity Research.

Jones

“The classic thing we do is to ask people to eat less and move more. The hard reality is that it's hard to lose weight and even harder to maintain that,” Jones said. “People try, and they don't lose as much as they would like to, and they quit trying.”

Results of a study led by Dr. Jian Zhang, a public health researcher at Georgia Southern University, were published in March in the Journal of the American Medical Association. A key finding is that there's a shift toward what the study calls “fat acceptance,” meaning as more people become heavier, it becomes the socially accepted normal body weight.

The study findings were gleaned through an analysis of government health surveys from 1988-2014 in which more than 27,000 adults ages 20-59 were asked if they'd tried to lose weight in the last year. In the early surveys, researchers say about half of those surveyed were overweight or obese, but that number grew to 65 percent by 2014.

In the earlier surveys, about 55 percent of participants said they were trying to lose weight - but that dropped to 49 percent in the more recent surveys.

The respondents may find that their own body is working against them, Jones said. “In The Biggest Loser, almost all of the contestants go back to their beginning weight, because the highest weight you achieve is what the brain thinks you should be,” Jones said of the weight-loss TV reality hit.

“Our bodies were designed in amazing ways, and for most of our functions, there are measures to keep us in balance. If your blood pressure gets too high, there are mechanisms to help the body lower it. If it's too low, there are physiological mechanisms to bring it back up to a normal range,” Jones said.

“But in the case of body weight, our bodies were designed to add weight and to maintain weight. Our bodies don't have a mechanism that says, 'You're too heavy,'” he said.

Hazlehurst resident Barolyn Amos knows well how hard it is to lose weight. For a decade, she's tried and mostly failed to stay the course.

“I'll lose a few pounds, then gain them back,” said Amos, 56. “Then, I started having health issues that got in the way and made it even harder. I finally said I'd give up on losing weight and just try to be healthy. It was time to put the Coca-Colas and stuff like that down.”

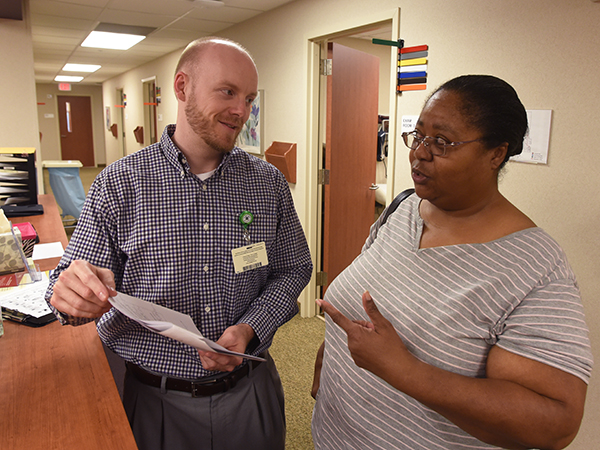

She's working with UMMC dietitian Paul Robertson to switch her focus to healthy foods and to exercise as she can. “I try to walk as much as I can. On my good days, I go by the gym and get on the elliptical.”

Although Jones is best known in the scientific community for his work in hypertension, obesity and weight management are common threads in his published papers and the clinical trials he has overseen.

“As we sit at our desk, we get a paycheck at the end of two weeks, and we go to the store and buy groceries. They are high-calorie foods at a relatively low price, compared to in the past.” Jones said. “If one wishes, one doesn't have to exercise or expend calories to get the food. That's the core problem.”

Vick

“I think social acceptance is probably not intentional. It's based on what we see around us,” said Dr. Kenneth Vick, associate professor of surgery and a key player in the growth of UMMC's bariatric surgery program. “What we see around us is an average weight increase in people, so a lot of times, people may not look inward and see themselves as standing out.”

So where does that leave Mississippians who want to lose weight -- who need to lose weight -- but aren't?

Improve the honesty and forthrightness of the physician-patient relationship so that the two are working together as a team, Jones and Vick suggest. And, make the patient's current and long-term health outlook part of the conversation.

“Talking about weight is a sensitive issue for some patients,” Vick said. “Most of the time they know it, but sometimes it's hard to start that discussion, and to establish a physician-patient bond without offending the patient.”

Practitioners sometimes miss a boat when talking to a patient about how much weight they need to lose, Jones said. “If someone's ideal body weight is 125 and they're at 175, if the conversation says get down to 125, the patient may lose 10 or 15 pounds, get discouraged and quit.

“Instead, a key message can be to begin with a 10 percent loss of body weight - for example, 17.5 pounds for someone who weighs 175,” he said. “They don't have to get down to 125 to get the health benefits. Controlling their health problems will be much easier, even with the 10 percent loss.”

It's a philosophy Amos is embracing. “I'm willing to start low and go from there. I'm realistic.

“Even if it's not but 20 or 30 pounds, I'd be happy, said Amos, who'd like to lose 100 pounds in her quest for health. “I just want to take some of the weight off that's making me sick.”

The challenge, Vick said, is finding the most tactful way to productively approach a patient about obesity or overweight. “Sometimes, I have a patient who says, 'My provider talked to me about it and said I need to lose weight. I know I need to lose weight. I just don't have solutions on how to do that.”

When an overweight person isn't coping with chronic diseases, “you have to establish trust and a good relationship with a patient so that they will understand that the doctor has seen this many times, and they know where this is headed. The vast majority of people who are significantly overweight won't be healthy forever.”

Physicians also must work with patients so they won't succumb to social pressure. “As more people become overweight, modern culture takes over,” Jones said. “This year's Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition for the first time is featuring fuller-figured models. Unlike 10 to 15 years ago, now you're seeing full-figured models, because that's who Victoria's Secret is trying to sell to.

“In marketing, they're not concerned about the health issues.”

Vick's specialty is bariatric surgery, procedures performed on the stomach or intestines to induce weight loss. It offers the morbidly obese an option that's more rapid than with conventional diets, and it can save the lives of patients who suffer from obesity-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes. Usually, the surgery is performed only after the patient has tried multiple times to lose weight.

But Jones and Vick both say bariatric surgery isn't a quick fix for obesity. “It doesn't need to be the first option in the vast majority of cases,” Vick said. “Even after bariatric surgery, they will deal with this for the rest of their lives.”

“Bariatric surgery is not a population solution to the problem, but for some patients experiencing the complications of obesity, it's an appropriate treatment as we continue to look at better solutions,” Jones said. “It's a Band-Aid.”

Amos isn't a candidate for bariatric surgery, so a thoughtful weight management plan is her best option. “It's a matter of being healthy,” Amos said. “I want to live a long time.”

The science of obesity is more complicated than other sciences, Jones said. That's one reason why researchers at MCOR tirelessly search for solutions to “the repetitive cycle of eating too much and gaining weight.

“God didn't have the grace to give us a counter-mechanism for weight management, but if we continue to invest in the science, we will get to better answers down the road, better tools and better medications,” Jones said.

“I've never see a patient who says, 'I want to be this big because I like the way I look.'''