The Organ Trail: In the beginning, there was the lung

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an edited version of an article from the current issue of the medical alumni magazine, Mississippi Medicine. The recollections of Ruby Winters were taken from a 2015 interview, with her permission.]

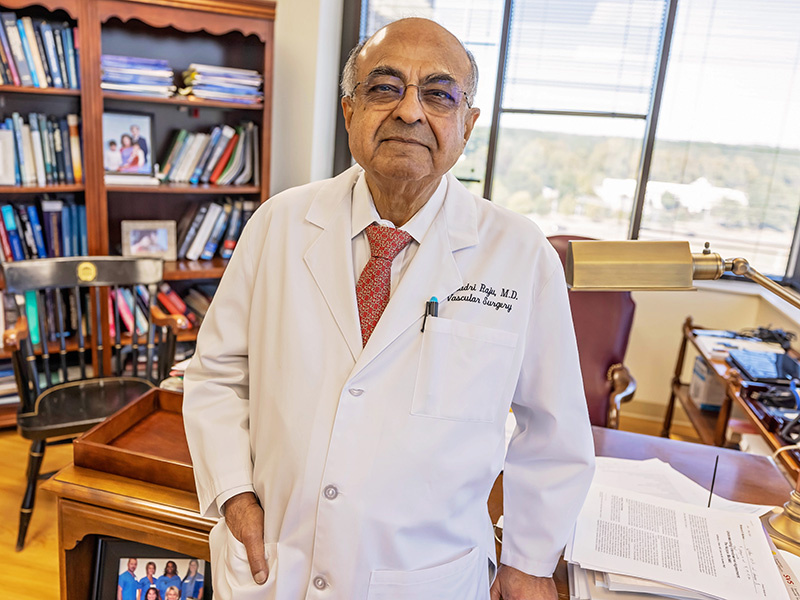

The winter sun had bled out and sleet stabbed the tarmac as Dr. Seshadri Raju arrived at the Jackson airport wearing his best blue polyester suit so appropriate for India’s tropical clime.

Told that the weather in Jackson was warm and humid, Raju shivered from the cold and exhaustion following a day-and-a-half flight that had ended on the Saturday before New Year’s Eve, 1967.

“The immigration people in New York were rude,” he said, “and the weather in Mississippi was ruder.”

Already homesick on his first trip outside of India, he considered going back – until the hand of a famous surgeon brought him in from the cold.

Moments later, plowing through slush in an Oldsmobile station wagon the size of a small iceberg, thawing in the warmth of the greeting from its driver and his gracious wife, “Weezie,” Raju found that “all gloomy thoughts and trepidation of an unknown future had disappeared.”

It would be a future of professional opportunities and kindnesses afforded him by the man behind the wheel. And it was beyond anything he could have imagined when he boarded the flight half-way around the world to train under Dr. James Hardy.

GRIT AND THE GODFATHER

It was like going to the moon.

“It was earth-shattering.”

Raju could be referring to either one earth-shattering event or the other, or both: 1. the world’s first human lung transplant; 2. the world’s first animal-to-human heart transplant.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Dr. James Hardy and his team performed them both, and so the whole world heard about the hospital in Jackson, where surgeons did something not dared before.

Dr. Seshadri Raju

“I believe others were waiting for a physician like Dr. Hardy to push the boundaries, for someone with the boldness it takes to do something brand-new that involves life and death,” said one of Hardy’s residents, Dr. Ralph Didlake, former professor of surgery and associate vice chancellor for academic affairs at UMMC.

One heir to this legacy is Dr. Chris Anderson, the James D. Hardy Professor and Chair of the Department of Surgery, who was part of the team that, in June 2022, performed the Medical Center’s 3,000th organ transplant.

“Dr. Hardy’s determination and intellect, his curiosity and grit – I look up to him a lot for that,” Anderson said. “It’s an honor to be the chair in his name.

“So much was different in the 1960s. There was no such thing as brain death. Organ donation was a foreign concept.”

Ruby Winters, 93, of Jackson, a retired RN who worked with Hardy, remembers the pioneering surgeon well. “People feared him,” she said. “He was just the way he was. But we got along just fine. If I hadn’t known what I was doing, I guess it would have been worse.”

But Hardy also had another side. Raju, who had been recommended to Hardy by Dr. James Hendrix, a plastic surgeon he met when Hendrix visited India, was struck by his mentor’s thoughtfulness.

His first encounter with Hardy’s thoughtful side was on that cold December night of polyester and sleet.

“Dr. Hardy and his wife put me up for the night. He took care of me … . He was like a godfather to me.”

Five decades after coming to America, Raju would publicly describe his debt to Hardy: “He lifted me on his shoulders, so I could reach higher than my own short height.”

Raju was speaking from the heights of a podium – as a 2018 inductee into the Medical Alumni Chapter Hall of Fame.

Hardy, too, is in the Hall and, likely, was destined to be so as of 60 years ago on a violent summer night in Jackson. Many people still remember that date – as the night Medgar Evers died.

BITTER AND SWEET

At midnight, June 11-12, 1963, Hardy’s resident, Martin Dalton, left Hardy’s side to answer a call to the ER.

Dr. James Hardy, known as a “fearsome disciplinarian,” was also like a “godfather” to Dr. Seshadri Raju.

There, as he would relate later, “I found a young black man with a massive chest injury” from a rifle bullet. The patient suffered multiple wounds to the left lung, the same organ Hardy would salvage later from another man in another room.

Describing his success decades later, Hardy wrote: “Certainly, the combination of participating in the first lung transplantation and the demise of Medgar Evers was one of the most bittersweet days of my life.”

The June 13 edition of The Clarion-Ledger devoted four front-page stories and a photo to the murder of the prominent civil rights activist. Death, too, can be earth-shattering. At the bottom of the page, the world’s first human lung transplant was chronicled in 187 words; it made no mention of Hardy’s, or any other surgeon’s, name.

Soon enough, there would be plenty of credit, and censure, to go around.

By then, Hardy, an Alabama native, had been at UMMC for eight years, recruited in 1955 to found a Department of Surgery at the new four-year medical school.

As a young man, he made a vow repeated in a biography by Dr. Marc Mitchell, UMMC professor of surgery and former Hardy department chair. Leaving home for college, Hardy announced: “‘… I had milked my last cow and taken my last dose of castor oil.’”

He had decided he would get other people to take their medicine instead, and milk his chosen profession for all it was worth.

LUNG AND HEART

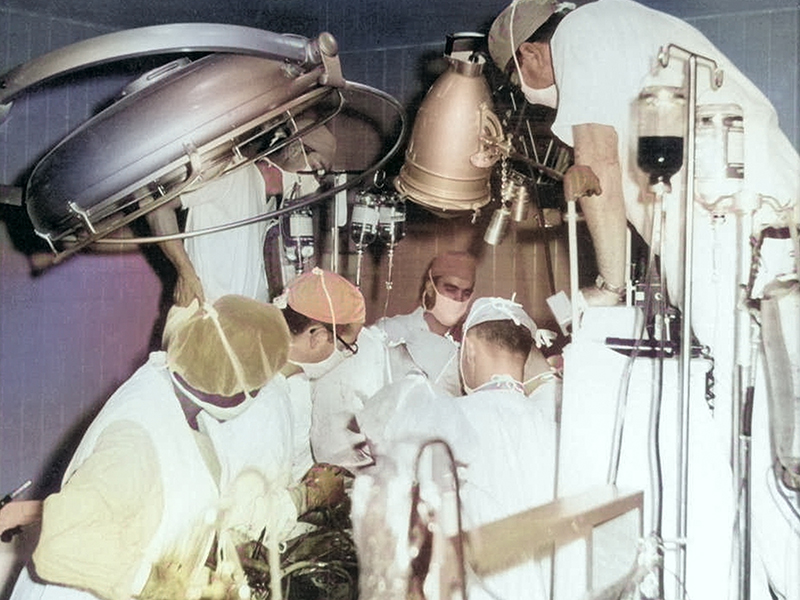

Ruby Winters was in the OR with Hardy just a few months after he had prophesied in a speech across the ocean in Liverpool: “Gentlemen: lung and heart transplants will be performed in humans in the very near future.”

Ruby Winters holds her nursing school graduation photo from 1949.

Back home in the USA, he made it so after years of lung transplant experiments on hundreds of animals, a project he spearheaded with Dalton.

On the night Evers died, it was Dalton who tried to resuscitate another patient – who suffered a heart attack. The man might not have been the first patient to die in the ER that night, but he would be the first in the world to give up his lung for another human.

His beneficiary had been sentenced to life imprisonment by the state and, potentially, to death by lung cancer. He also had chronic renal disease.

John R. Russell had been admitted to University Hospital in April; when he was told that transplantation might save his life, he consented. Hardy and Dr. Watts R. Webb had permission from the administration to perform a lung transplant. Two months later, the donor and recipient teams went to work.

“The patient recovered from the operation promptly and the transplanted lung functioned immediately …,” Hardy wrote later. Russell would die in 18 days – from kidney failure.

But the transplanted lung, according to Hardy, “exhibited only minor evidence of rejection … . We concluded that clinical lung transplantation was technically feasible… .”

Winters, who had been at Hardy’s side during the operation, knew what was coming: “After the lung, we knew Dr. Hardy was going to do a heart.”

HELL, AND THE SOUL

The night of the transplant, a medical student rode in a hospital elevator with a chimpanzee named Bino. The animal, which lay under a sheet on a gurney, was about to surrender his heart.

That medical student, and future Medical Center leader, Dr. James Keeton, witnessed many seminal Medical Center events. He was there for the first ground-breaking transplants.

“The heart transplant probably stirred up the health care world for the University of Mississippi more than anything else at that time,” said Keeton, vice chancellor emeritus for health affairs and dean emeritus of the School of Medicine.

“Dr. Hardy caught a lot of hell. Some accused him of showmanship.”

The “hell” he caught arose from this question: “Where was the soul?” Raju said.

“Some thought it resided in the heart instead of the brain.”

PREJUDICE AND PRIDE

On Jan. 23, 1964, just seven months after the first lung transplant, Hardy and his team put Bino’s heart into the chest of Boyd Rush.

Rush had lost his left leg to amputation because of gangrene resulting from hypertensive heart disease. His blood pressure had dropped fast. He was attached to a heart-lung machine.

Trying to preserve Rush’s life, one team of surgeons removed the donor heart in one room while, in another, Hardy took out the heart that had kept pumped life into Boyd for 68 years.

Following the one-hour operation, Boyd lived about 90 minutes. “The chimp heart wasn’t large enough to carry the human load,” Raju said.

Still, the surgical team’s work proved that heart transplantation in humans could work.

Still, “immoral” and “amoral” were among the judgments that stuck for years to this breakthrough. Hardy, who died in 2003, described in his memoirs the impact on him: It was “as if there had been a recent bereavement in the family, for the lung and heart transplants were never mentioned by friends.”

TIME AND SPACE

After a space, redemption began. “Slowly, but surely, Dr. Hardy got his reputation back,” Keeton said.

In fact, Raju said, “every organ you can think of in transplantation, the fundamental principles involved, came from the Hardy laboratories… .

“And I would not be who I am without UMMC. I owe my professional status to Dr. Hardy and to the training he gave me.”

Now at St. Dominic Hospital in Jackson, Raju, a vascular surgeon who helped transform the treatment of diseases of the veins, left the Medical Center around 1992.

Before that, he performed the first clinically successful double lung transplant in the United States and the first successful heart transplant in Mississippi. For both those pioneering surgeries, at Raju’s request, a certain retired surgeon stood at the head of the table.

“Dr. Hardy watched his lifelong quest come to fruition,” Raju said, “albeit through hands he had trained.”