Rural Electrification: Physicians/students bolt for communities that shaped them

Editor's Note: This article first appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Mississippi Medicine.

"Why would a doctor come here?”

In Mississippi’s many small, out-of-the-way places, where patients need doctors most, the question persists.

For medical students, there are financial enticements, scholarships and other awards to help get them there eventually. But there are other motivations that don’t come with dollar signs. Like the satisfaction that comes from serving people who often have few means, who may have to hold down more than one job to get by, and who are more likely to live longer, and healthier, with another doctor in town.

There are the rewards of being a part of a close-knit community, a place where you can thrive, not only in your career, but also in your personal life, where so many people will know you not just as their doctor, but also as their friend.

Following are the stories of two physicians and two future physicians who know this joy. Perhaps their stories answer the stubborn question best.

— — —

Caring for Carthage

One day last fall, Bonnie Scott drove 10 miles from her home in Walnut Grove to see one of her “babies.”

This “baby” stood more than six feet tall, wore eyeglasses, turquois scrubs and a stethoscope.

Years ago, Scott had the answers to his questions about reading, writing and arithmetic; she was his substitute teacher then. Today, he answered her questions about her kidneys; he is her physician now.

He is Dr. Jonathan Buchanan (’14), who graduated from high school in Carthage, left his hometown, then returned with another dozen years of education behind him, including his MD from the University of Mississippi Medical Center and a residency in family medicine.

“There were only three physicians here when I came back, in 2017,” he said of Carthage, a town of about 5,600 some 55 miles northeast of Jackson. He was the first to return to the area in 26 years.

Dr. Jonathan Buchanan’s (‘14) patient, Bonnie Scott, is his former substitute teacher. Now, he’s the one giving her tests.

“I got a very warm reception,” he said. “Because I’m from here and many of the families here already knew me, their trust in me as a physician was already built in.

“Plenty of people have told me they didn’t think about seeing a physician until I moved back. If you weren’t an established patient, it took so long to get in to see a doctor.”

On Mississippi 16, across the street from a barn that looks ready for Medicare, is Baptist Medical Center Leake in Carthage, where Scott got a checkup from one of her former students, or “babies.”

She could have gone to a Baptist satellite clinic in Walnut Grove, but prefers to see a doctor who couldn’t spell “doctor,” when she first met him.

A doctor who has a history with her family and with the community where his parents still live and where he has started a family of his own: The day after Scott’s clinic visit, Buchanan’s wife, Candice, gave birth to their second daughter, Blair.

A doctor who had gone to school with Scott’s daughter from kindergarten through high school. “As a student he was well-mannered and loved by everyone,” said Scott, 61. “As a doctor, he talks to you on your level.”

Buchanan comes from that level: a small, rural Mississippi town, where he grew up as “a pretty healthy kid who didn’t have to go to the doctor often,” he said. It was just as well.

“When I was 16, my dad had a heart attack and went to the ER, but had to be transported to Jackson to get the care he needed,” Buchanan said. This stuck with him through college, at the University of Southern Mississippi; that’s where he decided he would go into medicine and help fill the health care gap he knew personally, he said.

“Having gone through that experience with my dad, I wanted to be the type of physician who was approachable. To be able to offer the support that comes with providing primary care.”

As a Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar, he pledged to provide it in a place like Carthage in exchange for a financial grant. He has surpassed the conditions of his four-year commitment, but he’s staying put.

Carthage is good for his family, he said. But it’s not just his own family he’s thinking about.

Plenty of families in Leake County face chronic disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol. Plenty need specialty treatment but often have to drive to Jackson or Meridian to find it.

“That’s a total of two hours,” Buchanan said. “It’s absolutely a hardship for some patients.

“We’re a small-town community; a lot of working-class people,” Buchanan said of Carthage, whose population is about 48 percent African American, U.S. Census figures show.

“It’s a big deal to take off work to go to the doctor. So, I want to do everything possible within my own specialty before I have to tell a patient we need to find them another one somewhere else.” Before their health suffers so much, like his dad’s.

His devotion to his patients was recognized last summer by the Mississippi Academy of Family Physicians which named him New Physician of the Year.

“When I went through the Mississippi Rural Physician Scholarship Program, I made a commitment to work in a rural area,” he said, “but, honestly, I knew I was going to do that when I first arrived at the Medical Center.

“And it’s been everything I wanted it to be.”

— — —

Wistful in Waynesboro

As Vertoria Rivers gazed at the murky, peanut-size image that was her baby on ultrasound, the words “Hi mom” popped up on the screen.

Rivers, due in July, now had the first-ever photo of her baby, taken inside the Waynesboro Family Medicine and Obstetrics Clinic.

During her OB-GYN rotation with Dr. Ross Sherman (‘90), background, Mia McFadden performs an ultrasound for patient, Vertoria Rivers. “She’s a star,” Sherman says of McFadden.

It was a souvenir from the ultrasound typist, third-year medical student Mia McFadden, and her typing coach, Dr. Ross Sherman (’90), who taught McFadden how to manipulate the machine’s traducer.

That was not the only thing she was learning during her OB-GYN rotation with Sherman in her hometown of Waynesboro last fall.

“She’s a star,” Sherman said of McFadden. “Always ready to work and to learn.”

McFadden is a Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar who grew up in the town of about 4,600 residents, more than 60 percent of whom are African American. It’s known for its setting on the Chickasawhay River, the rugged reputation of its high school football teams, and swamp fries from Mississippi Fried Chicken and Bar-B-Que.

It is not known for its wide selection of OB-GYNs – and yet Rivers, 30, said she drove 12 miles from her home in Buckatunna to see Sherman, who also grew up in a small town: Wiggins, population: 4,300.

“You may have morning sickness,” he warned Rivers. “That’s why God made me a man. He knew if I had morning sickness I would die.”

For Rivers, Sherman is the nearest OB-GYN doctor she could find, and McFadden’s presence was a bonus. “They are really sweet,” Rivers said. “If they weren’t here, I would have to go to Laurel.” A 90-minute drive from Buckatunna, roundtrip.

In fact, Sherman trained in family medicine, but completed a fellowship in OB-GYN. He is the only physician in Waynesboro with that level of OB-GYN training, he said, “but another one is coming from Alabama to the clinic – in August.”

For her part, McFadden is strongly considering returning to her hometown as an OB-GYN. “I want to help women better understand what they’re going through, especially because of my experience with my mom,” she said.

Demarius McFadden, a school teacher and LPN, had breast cancer, but the nearest cancer center was in Laurel, about 30 miles away. Eventually, she had to go to Georgia, to Cancer Treatment Centers of America. McFadden’s mom died in 2018.

Medical student Mia McFadden, who grew up in Waynesboro, is considering returning to her hometown as an OB-GYN.

“When I finish my training, I want to go back home because I’ve seen first-hand how difficult it can be to get care,” McFadden said.

“Everybody deserves good health care. They’re human beings. But it’s hard to find healthy choices in rural towns. And people are faced with working paycheck to paycheck; they can’t afford to take off work and go to the doctor.

“When I was girl, there were no specialists here. We had a pediatrician for a while, but she moved. My parents had to take me to Laurel. For some specialty care, we had to travel to Meridian, almost an hour away.”

Today, Wayne General Hospital offers an emergency department, a midwifery service, but not many specialists.

A half-dozen physicians practice in Waynesboro, Sherman said. He hopes McFadden will join them one day. She’s anticipating what that will be like.

“Patients will trust me and follow up more,” she said, “including those within the African American community who decide to come to me, an African American woman.

“Being from here, you have an extra tie with your patients: ‘I know your mama. I know your daddy.’ I get to be like their family. I will care for them deeply and they will know that.

“I can’t wait for a patient to bring me some cucumbers or tomatoes.” One day, Vertoria Rivers’ baby might be one of them.

— — —

Faithful to Philadelphia

For Emilio Luna-Suarez, the distance between his home and his wife’s doctor was not measured by clicks on the odometer, but by the beats of a heart: his child’s.

Luna-Suarez says he plans to return to Philadelphia. “There are rewards there for my family. And for me as a doctor; having that personal relationship with people in my hometown – that’s going to be really rewarding.”

During the peak months of COVID, his wife Madison, a software engineer, was expecting their second baby. There was no OB-GYN physician near their place in Neshoba County; she found one in Flowood – more than an hour’s drive away.

“She really did not want to miss her appointments for the baby during the pandemic,” Luna-Suarez said, “so, if her employer had not let her get off of work, she might have had to quit her job.

“I can’t imagine how hard it is for people who can’t even afford to take off from work to go to the doctor – what do they do?

Luna-Suarez, a third-year medical student, was born in Alabama, but his family moved to Mississippi when he was 2, about 25 years ago. His mother was from Meridian; his dad had immigrated from Mexico.

Mostly, he grew up in Philadelphia, in Neshoba County, where many people farmed or logged for a living. “We came from a very poor background,” he said.

Medical student Emilio Luna-Suarez, with wife Madison and their children, Alice, left, and Asher, says that he knew by high school “that whenever I had kids, I didn’t want them to have to grow up in poverty, or have to help their mom pay the bills like I did growing up.”

“By high school, I knew that whenever I had kids, I didn’t want them to have to grow up in poverty, or have to help their mom pay the bills like I did growing up.”

As a child, he was plagued by asthma and allergies; for treatment, his parents took him to nearby Union -- just because they knew the doctor there. He doesn’t know if Philadelphia had a pediatrician then. “I didn’t know what a pediatrician was,” he said.

While in high school, he wanted to go into nursing. He’d had a taste of that already: “My grandmother couldn’t get around well enough to bathe and otherwise take care of herself well,” he said, “so, I helped take care of her.

“I didn’t know why stuff was happening to her and I needed to know the reasons behind the pathology.” The first in his family to go to college, he had “gotten a free ride” at Mississippi State University; there, he decided to change his major from nursing to pre-med.

In medical school, he arrived as a Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar. Last fall, he did a rotation in a pediatric clinic in Grenada, a small town but significantly larger than Philadelphia.

Even so, Philadelphia, bejeweled with casinos and resorts and about 7,000 people, is “booming” today, he said. “In health care, it offers a lot more than many other rural communities. But there’s still no OB-GYN. There are hardly any specialists.

“So, no matter what specialty I may choose, I’m going back to Philadelphia. There are rewards there for my family. And for me as a doctor; having that personal relationship with people in my hometown – that’s going to be really rewarding.

“The need for health care in rural Mississippi is so great. There aren’t enough doctors.

“But that didn’t really hit me until I had my son.”

— — —

Babies for Brookhaven

During her childhood in Kokomo, Dr. Carolita Heritage (’15) said, the Marion County settlement had a “tiny post office, a gas station and a restaurant.”

About 150 people live there today.

Dr. Carolita Heritage (‘15), an OB-GYN in Brookhaven, grew up in Kokomo, where she knew of women who had delivered their babies in cars because they couldn’t make it to the nearest hospital some 90 minutes away.

Growing up there, Heritage worked with her father and brother with the volunteer fire department. She saw a lot of accidents; sometimes she would try to comfort the relatives of the victims as they waited to see if their loved ones had survived.

She knew women who had delivered their babies in cars because they couldn’t make it to the nearest hospital some 90 minutes away.

“Hearing those stories in our community, I was drawn to women’s health,” she said. “It made me want to provide better care for women.”

Heritage, who has been one of Brookhaven’s 12,000 or so residents since the summer of 2019, chose to settle in Lincoln County’s principal city because of its location: about halfway between her husband’s family in the Canton/Gluckstadt area and her parents in Kokomo, situated not far from McComb.

At Brookhaven OB-GYN Associates, where Heritage works, patients come from as far away as Natchez, Liberty, Vicksburg, Tylertown, Prentiss, Columbia and Brandon.

Of those small cities and towns, the nearest to Brookhaven is Prentiss – 36 miles, one-way – while Vicksburg is the most distant at 76.

Many of those places, or others nearby, are not bereft of physicians, including OB-GYNs.

“The medical community here is well-respected,” Heritage explained, “and Brookhaven is easier to navigate than some larger towns. Patients don’t feel so overwhelmed.

“Some of these towns have hospitals that deliver babies, but they may not have as many physicians who have been around for as long as the OB-GYNs we have here. There are five and some have been here for 25 years or longer.”

Another Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar, Heritage has exceeded her rural practice

obligation, but has no plans to leave. She likes living there, the home to the Haven Theater,

Wolf Hollow Golf Course, Military Memorial Museum, Great Mississippi Tea Company and an array of diners and cafes, including the Wild Fox, Betty’s Eat Shop, Dude’s Hot Biscuits, and the Old Koke Plant.

She also savors her practice there. “One of the benefits of rural OB-GYN vs. OB-GYN in larger areas is that I tend to have a lot more continuity with my patients,” she said. “I get to deliver the majority of them, along with their cousins and friends. Word gets out.”

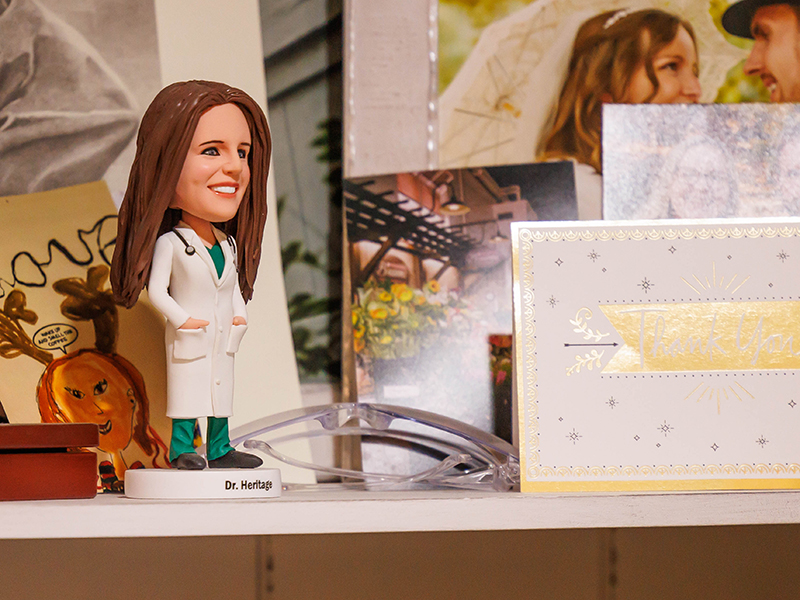

Along with medical equipment and an illustration of a uterus, Heritage’s office is made cozier with personalized gifts from her patients.

She is committed to getting out the word as well – to future physicians by letting them shadow her. Last fall, for instance, Chafic Dahabra, a third-year student from the William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, was on a core rotation with her when he witnessed a birth, or, as he put it: “I caught my first baby.”

Heritage hopes she can catch Dahabra or others like him when they decide where to practice. “The biggest thing is to find physicians to replace those who are retiring and to keep rural hospitals open,” she said. “That’s what we physicians are focusing on here.

“We’re not replacing physicians as fast as they are retiring. Across the United States, I believe, this is an issue, especially in rural towns.

“The more often rural docs are taking students, the more we can show them the advantages of a rural practice. It’s a misunderstood lifestyle. I believe if students would come to places like Brookhaven, they would enjoy it – the continuity, the community.

“It’s just different – seeing your patients at events in town; running into them at the shops where you shop. Seeing their families grow.”

Her patients recommend books to her, she said. They make things for her, including her own nameplate fashioned from Scrabble tiles adorned with a tiny “uterus” – she loves board games.

From her desk, she picked up a pen a patient had made for her and rolled it gently between her fingers as if it were made of glass or gold.

“On stressful days,” she said, “things like this keep you going.”