ARIC celebrates 30 years of community, research

Changes happen with age. Blood pressure rises, as does the risk of other cardiovascular diseases.

Who is most susceptible to these changes? Why do they happen? And, perhaps most importantly, how can we use this knowledge to make people healthier?

Big questions require big studies. For 30 years, the University of Mississippi Medical Center has been looking for the answers through the Jackson field site of the landmark Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, or ARIC.

“The main focus [of ARIC] is elucidating the risk factors for heart disease and stroke and determining how that varies by sex, race and geography,” said Dr. Tom Mosley, principal investigator for the Jackson site.

Since 1987, ARIC has followed approximately 16,000 participants in Jackson; Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; and Minneapolis, Minnesota from midlife onward, investigating the origin of diseases associated with atherosclerosis, the hardening of blood vessels.

ARIC conducts physical exams for its participants every few years, including blood samples, electrocardiograms and other tests, as well as phone calls every six months. Mosley said that “exquisite measures of vascular markers” have allowed the study to make discoveries that few others can. More than 1,900 scientific papers and 300 ancillary studies use the ARIC data to answer questions spanning far beyond its original scale.

While the study retains its focus on cardiovascular diseases, its scope has grown with time.

“Now, we can study genetics, kidney disease, cancer and brain aging,” Mosley said.

Before he joined ARIC in 1993, Mosley conducted memory assessment studies in UMMC's Division of Geriatrics. The studies would have about 50 people - “small potatoes,” he said. Through former ARIC leaders and UMMC faculty Dr. Richard Hutchinson and Dr. Bob Watson, Mosley saw an opportunity to expand into a much larger cohort.

“ARIC was one of the earliest studies to look at brain aging in a population,” said Mosley, who became PI in 2003. In 2010, he and colleagues started the ARIC-Neurocognitive Study, which “leverages rich longitudinal data to study how the brain ages.”

For example, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that ARIC participants with multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors had a higher risk of developing amyloid plaques - an Alzheimer's disease marker - decades after their initial exams.

“We've found that the underlying pathology doesn't start at the first sign of memory loss,” said Mosley, Hughes Chair and Director of the MIND Center at UMMC. “This is important because we know the time to try to limit the risk of dementia is when people are in their 40s and 50s, not 70s and 80s.”

This wealth of knowledge provides the basis for the MIND Center, which conducts research and provides treatment for patients with Alzheimer's disease and similar disorders.

The success of the ARIC Jackson site - which recruited 3,722 African-Americans - was also a determining factor to create the Jackson Heart Study, the largest study of African-American cardiovascular disease. The two studies share some of the same participants.

“We've had this wonderful wealth of information,” produced by ARIC, said Stacee Naylor, clinical research manager for the study. She said retaining as many participants as possible is challenging, but vital to keeping the study going,

“We keep in touch through phone calls, birthday cards, scientific updates and newsletters,” Naylor said. “We make sure to thank the participants for their commitment to this effort.

To celebrate 30 years, the Jackson field site honored hundreds of participants and their families at an appreciation luncheon June 3 at the Hilton Jackson.

“When I arrived this morning and couldn't find a place to park, I thought it was a success,” said Dr. Robert Smith of Central Mississippi Health Services.

Smith, an ARIC investigator, said the study was a “tough sell” at first for himself and the community, considering the history of unregulated research on African-Americans.

“I traveled to Washington to make sure that national ethical standards would be carried out,” he said. “I'm delighted looking back, thirty years later, on the opportunity it's created in terms of being a practicing physician and for educating the community in general.”

“What made me interested was that [ARIC]… would benefit and could benefit others,” said participant Dorothy Jenkins of Jackson. “I'm a person who always liked to do things that help myself and help others.

“I just knew that this was something that I would like to do. So I ended up signing up for it, and it's been a journey.”

“I want to extend my thanks to all of our participants throughout the years,” Mosley said. “Their contributions are making us and the future healthier.”

Mosley said the study is still in contact with ninety percent of the living participants, evidence that retention efforts work. The cohort receives some benefit from the study as well.

“There's evidence that people who participate in medical research tend to live healthier lives,” Mosley said. “The ARIC participants receive some of the most advanced screenings available, such as EKG and brain MRI.” Sometimes, they find underlying health conditions at the visits, such as atrial fibrillation or tumors, which might not have been noticed as early.

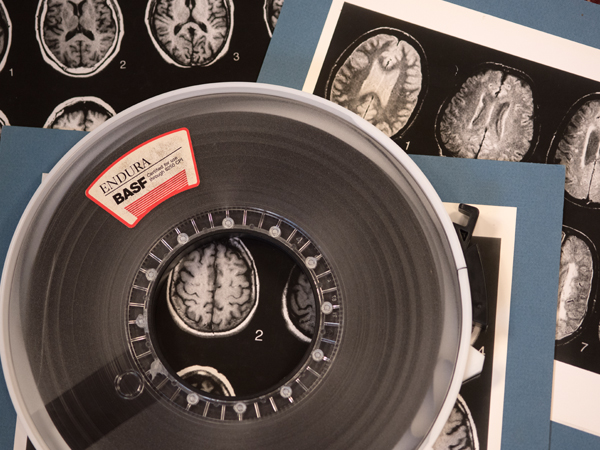

As ARIC continues into its fourth decade, medical technology has changed as well. Mosley keeps a record-size roll of film and a photo array of brain scans as a reminder.

“This holds one person's brain scan,” Mosley said of the first, “and the photos are representative of different levels of brain loss associated with dementia.”

Today, the study can keep all of the scans on hard drives. The photo lineup has been replaced by sophisticated software that can not only measure the structures of the brain, but estimate their functional ability via the level of connectivity, Mosley said.

The ARIC cohort members are currently 70-90 years old, but Mosley doesn't see the study ending anytime soon. With exam visit six underway and funding for a seventh, it's set to run through 2019.

“We are also considering a second-generation study that would include the original cohort's children,” he said, which would open opportunities to study familial patterns.

“Our work's not done yet.”

The ARIC study is supported by the National Institutes of Health.