Jackson-Williams guides new/old Office of Medical Education

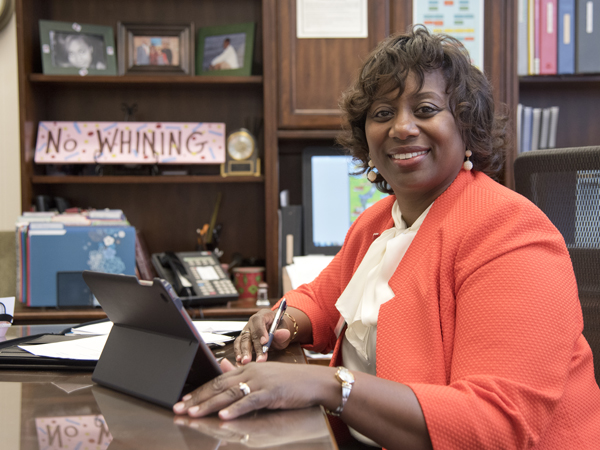

Dr. Loretta Jackson-Williams has a new title for pretty much the same job, working in the same office that now has a different name.

The changes, announced this summer, may sound like little things - "vice dean for medical education," instead of "associate dean for academic affairs;" and "Office of Medical of Education" instead of "Academic Affairs, School of Medicine."

But, as she says, "little things can be really important." Things like a motivating word from a teacher, a frog in a high school biology class, a garden full of hot misery and field peas, and a small-town upbringing with sidewalks and roller skates.

Little things that leave big impressions, as they have with her.

These things have followed her throughout her career and life, which she describes by dwelling mostly on the instructive, cheerful and sometimes perplexing details - like the time she considered becoming a lawyer.

"But I realized that lawyers often become judges, and making life-and-death decisions was not for me," she said. "Think about the irony of that."

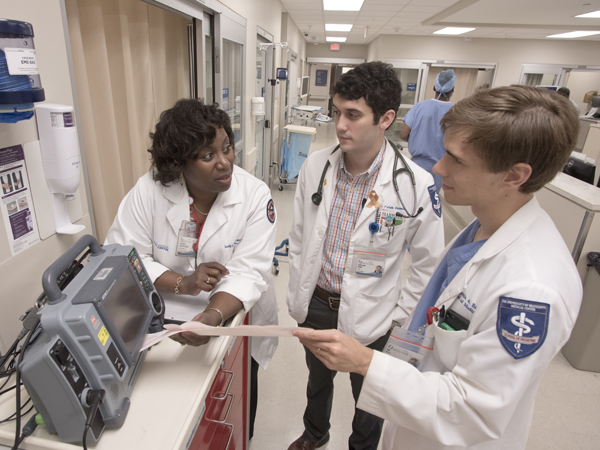

The irony is that she not only became a physician, but she also got her start in the emergency room, where life -and -death is your bread and butter.

Today, she is also a professor of medicine in the Department of Emergency Medicine. "If I hadn't become a doctor, I might have been a teacher, which I am sort of, anyway," she said.

Her affinity for students is obvious in her work as Medical Center leader, said Dr. LouAnn Woodward, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

"She excels at seeing the big picture - not only viewing things through the lens of her own specialty, but also working for whatever's best for the student or program. That is hard to find in a physician leader. And even though she does not accept defeat and is not afraid of making a decision, she also is fun to be around.

"And, on a personal note, she is a twin, and I have twin daughters. So she's been my source of guidance bringing up twin girls."

If not a physician, administrator, lawyer or educator, Jackson-Williams might have become an actor. But probably not.

Growing up in Indianola, she pretty much unmasked herself as a future doctor or scientist. She "thoroughly enjoyed" chemistry and "had a great time" in biology, especially when the class dissected frogs.

One of her favorite teachers at Gentry High School was her 10th grade biology instructor, Charles Scott. "I helped him teach dissection to the class," she said.

"He decided I was going to medical school." It wasn't a suggestion; it was a ruling.

Certainly, she had the grades. "My friends would ask me, 'How much did you get paid for your A's?'" she said. "Paid? A's were the baseline expectation in my house."

Her parents, C.C. and Queen Esther Jackson, were both educators, members of a church-going family whose second religion was scholarship.

"This was my parents' mindset: School was your job. When you made an A, you were doing what you were supposed to do," she said.

In this environment, you were also supposed to work in the garden, even on Saturdays. There were four children in the family: Loretta; her fraternal twin Claretta, now a science researcher; their older sister Mavis, now a retired teacher; and their brother Alvin, now a minister. All tilled and harvested the family's one-acre plot of field peas, minus an allowance to inspire them.

If they wanted new clothes for school, they earned money for that by chopping cotton.

"I completely understand that," Jackson-Williams said. "They raised us the way they were raised: You worked. You took care of your responsibilities. Their philosophy was that we had everything we needed, so if we wanted something extra in life, we worked for it. I learned that lesson well.

"I also learned to appreciate where food comes from. And I learned that I'd rather work indoors.

"So, a little bit of discomfort may spur you on to good things."

The good things, career-wise at least, may have gotten another boost with her 11th grade science project: "The Precision and Accuracy of the Piston Activated Pipette." This pipette, which uses a vacuum to precisely measure small amounts of liquids in laboratory settings, was relatively new at the time, and another little thing that proved to be important.

Years later, while earning her Ph.D., this device had become "second nature" in the lab. If she needed further proof that a career in science or medicine was for her, this may have been it. Her project placed in statewide competition and earned her a trip to New York City, where she took in her first Broadway play, "Showboat."

This was her opportunity to see actors live, instead of on a mere TV screen, and there was a time when she dreamed of being on a stage like theirs. The dream was about living and traveling in an exotic place beyond the Delta. "It was an aspiration toward an ideal," she said.

She even dabbled in theater, but found out she preferred the backstage to the spotlight. "I liked running things," she said. And her brother, whose opinion she valued, advised her against an acting career.

Even then, she often lived in a make-believe world, reading Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys mysteries as a child. In that time and place, a good imagination was not a luxury, and that was fine with her.

"We made our own fun out of what was there," she said. "It was growing up in a small place, being able to walk everywhere, playing cowboys and Indians and climbing trees. Skating up and down the sidewalk. I wish my kids had that."

She and her husband James Williams, a Tallahatchie County native and math specialist who works for the Washington, D.C.-based National Center on Education and the Economy, have two children: son Jordan, 20; and daughter Taylor, 15. When asked to describe the accomplishment she's proudest of, she names them.

Both have been brought up in Mississippi, mostly. Loretta and James returned here in the 1990s to be close to both sets of parents.

"While she's trained at fine institutions from coast to coast, in the prime of her career she's right back here in Mississippi making a difference," said Dr. Jerry Clark, chief student affairs officer and associate dean for student affairs in the School of Medicine.

"She's certainly empowered my work as a student affairs professional, fully recognizing that students won't do well inside the classroom or clinic unless we've been thoughtful enough to take care of things on the outside. I'm proud to be on her team."

But, for her, the road back home to Mississippi was anything but a straight one.

A graduate of Tougaloo College, where she and James met, Jackson-Williams found the medical school at Boston University appealing and enrolled in the M.D./Ph.D. program.

Long before that, she had her heart set on emergency medicine, thanks to a summer she had spent with her brother in Memphis. There, she had found a job helping out in the emergency department at The Med (Regional One Health).

"Every day I would come back talking about what I had seen that day. It was fascinating."

But, in 1994, the year she earned her medical degree, emergency medicine was still relatively new as a specialty. "Some people didn't believe it should be a separate specialty," she said.

Apparently, none of those people worked at Highland Hospital in Oakland, Calif., where emergency medicine had its own department - a rarity in those days. For that and a variety of other reasons, she chose to do her residency there, she said.

"Emergency medicine didn't have a shared identity at Highland. It didn't come from something else. This became very important to me."

Likewise today, as a leader at the Medical Center, she is helping her office fortify its own identity.

"The name 'Academic Affairs' doesn't encompass all of the responsibilities it has," she said. "The change to 'Office of Medical Education' will get people to pay attention to its function, which is more than just regulatory."

While the new title more accurately reflects what she was already doing, Jackson-Williams will have a broader decision-making duties, Woodward said.

The change also makes clear that the responsibilities of her position are separate from those of the institution-wide office directed by Dr. Ralph Didlake, associate vice chancellor for academic affairs and chief academic officer.

Clearly, those responsibilities are important, Jackson-Williams said. "But what we do outside the Medical Center is just as important."

In part, she was referring to the way she and her husband are bringing up their children. But outside the Medical Center, she is also known as a tennis player and a baker - her Facebook page recently blossomed with a photo of home-baked cinnamon bread.

She likes to travel, and hopes to do more someday. And she's still a reader, although she has graduated from the Hardy Boys to the likes of "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks," the true account of a young cancer patient whose harvested cells became priceless for medical research, including the development of in vitro fertilization and the polio vaccine.

Little things that became really important.