Black pastors, docs strive to dispel COVID-19 vaccine doubts

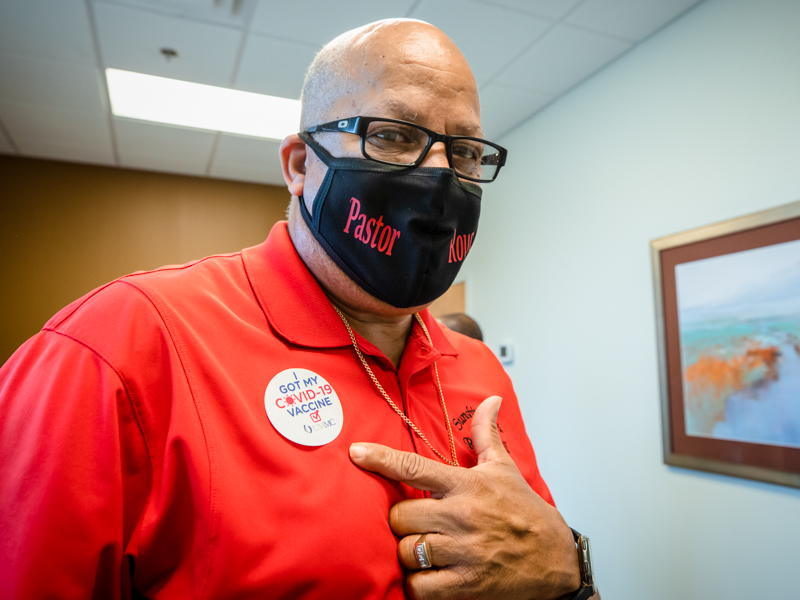

Last Wednesday, the Rev. Tony Montgomery Sr., pastor of Greater St. James Missionary Baptist Church in Jackson, pushed up his sleeve, sucked in his chest and took a shot at conspiracy theories, doubt, distrust and skepticism.

He took a shot of the COVID-19 vaccine.

“Oh, is that all?” he said after Babette Burke, a University of Mississippi Medical Center nurse, had withdrawn the needle, painlessly, from his arm.

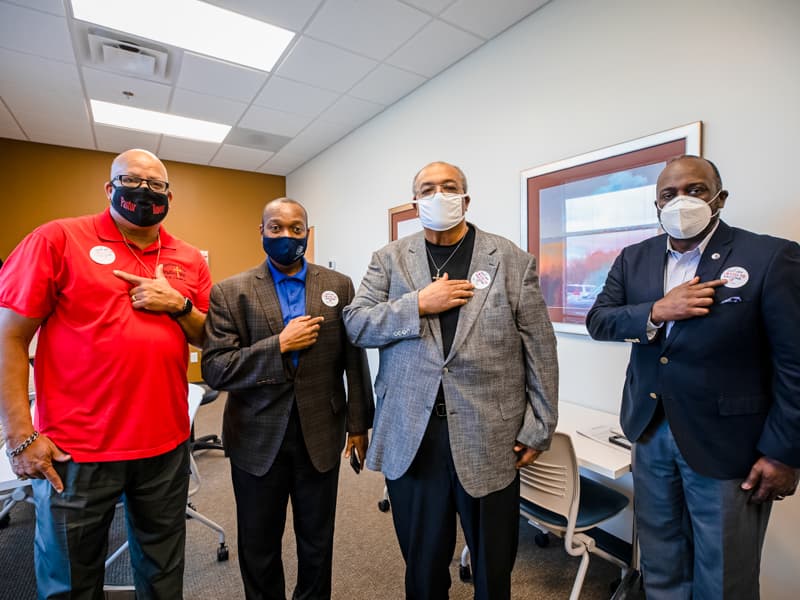

It was not all. Montgomery was one of four Jackson-area pastors who had met up at the UMMC Flowood Family Medicine Center that day, along with the Rev. Reginald Buckley of Cade Chapel Missionary Baptist Church in Jackson, the Rev. Keith Rouser of Ridley Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Madison and the Rev. Earnest Ward, associate pastor of Stronger Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Jackson.

They were there to demonstrate their faith – in the vaccine that has raised suspicions among some Americans, not least of all those in the Black community these clergymen serve.

“To be a pastor at this time is a gift,” said Montgomery, soon after getting his first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. “Pastors should not be the taillights on this; we should be the headlights. We should lead the way.”

The foursome’s show of unity is part of an ongoing drive signed off on by physicians at UMMC, among others. Earlier in January, five African American physicians also took their first dose of the Moderna vaccine during a similar event in Jackson.

Organizers of that do-as-I-do demonstration, like the one in Flowood, hope to encourage Mississippians, especially those within the African American community, to conquer their fears and skepticism about the vaccine, and to trust those who serve either their medical or spiritual needs.

Among the former is Dr. Demondes Haynes, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at UMMC, who has marshalled facts to tamp down his patients’ worries, including one social media claim that the vaccine is “going to change your DNA.”

“I’ve even had to talk to some of my own family members about this,” said, Haynes, who is also associate dean of Medical School Admissions.

“We’ve lost two cousins to the virus. I don’t think we need to wait for the federal government to begin educating more people about the vaccine. We need to start now.”

Only 17 percent of Mississippians who had taken the vaccine by Jan. 29, 2021 are African Americans, statistics on the Mississippi State Department of Health website show, compared to 69 percent for Whites (“Asian” and “Other” are among the additional categories; the latest figures are here).

Yet, Blacks/African Americans make up nearly 38 percent of the state’s population, with 59 percent for Whites.

As for COVID deaths by race: By late last week, Blacks/African Americans represented 42.2 percent of the 4,897 deaths recorded in the “Not Hispanic” ethnic category, with 55 percent for “Not Hispanic Whites.”

“The loss of loved ones and friends is something you have to come to grips with,” Rouser said. “You have to know this thing is real. When all is said and done, take the shot.”

Still, some black patients believe they are immune to the virus, physicians say, while others believe, as do many whites across the country, that the pandemic is a hoax, or that the vaccine bears a high-tech Trojan horse: a trackable microchip.

For his part, Haynes is starting at the place where he believes an anti-disinformation campaign will have a great impact, as the pastors will testify: church.

On Jan. 23, Haynes led a webinar at his own Sunday home, the Word and Worship Church in Jackson. A week later, this past Saturday at his regular home, he took on questions remotely from members of other congregations. He speaks with authority, not just as a physician, but also as someone who has received the vaccine – as the four pastors who met at the Flowood clinic can do now as well.

Some of those ministers used their smart phones to record videos of Burke working her needle magic on each other, planning to stream those images on their churches’ Facebook pages for the edification and mollification of the flock.

For Cade Chapel, its Facebook page alone reaches about 2,500 pairs of eyes, Buckley said.

“There are a lot of fears, a lot of healthy skepticism, about the vaccine the health care system, period. We’re doing this as faith leaders to show our faith, our belief, in science.

“This vaccine is not something cooked up at the last minute, where you throw everything into a pot and see what comes out, like gumbo. It didn’t start from scratch, and I believe that message needs to get out there more.”

Among those supporting that message is Dr. Shannon Pittman, who sees patients at the Flowood clinic. Some concerns about the vaccine are not unique to the black community – such as its safety and effectiveness, said Pittman, the Alma Lowry Hill Chair of Family Medicine at UMMC.

“We encourage African Americans to be vaccinated. However, members of the African American community can easily fall into conspiracy theories because there are increased risks for them concerning COVID.

“When it comes to the virus, we are a vulnerable population. There is also a historical narrative that is not built on trust. It lends itself to sound bites that heighten the distrust.”

It didn’t help that Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Hank Aaron died recently, just weeks after taking the vaccine, she said.

“So, I reference the facts to those patients who have these fears. COVID can be deadly, certainly, but more people recover than die. COVID can also have long-term disease complications even if you survive.

“Those are the things we know. The vaccine has been proven to be effective against the strains of COVID that are in our community. So if there is an opportunity to take something we know can be helpful to prevent something we know can be deadly, what is the good reason to not get vaccinated?”

Qualms are often based on, as Pittman said, “the historical narrative,” which includes the Tuskegee Study, an experiment in which black males with syphilis were deliberately untreated; scores died.

“But it’s not just about the past,” said Dr. Justin Turner, an internal medicine specialist practicing in south Jackson who serves on the City of Jackson Coronavirus Task Force. “A lot of these patients have had personal experiences that make them distrust the medical system.

“So I tell my patients: ‘I was a black man before I was a black physician. I, too, found myself asking some of the same questions you have: How do I know this is safe? How much can I trust my government when so much is politicized unnecessarily, and when there is so much inconsistency?’

“So I went back to what I know, and I asked questions, but I didn’t go to the Facebook School of Medicine. I spoke to [Dr. Thomas Dobbs, State Health Officer]; I did my research. And I say to patients, ‘The worst consequences from the vaccine cannot be worse than the worst consequence from COVID, and that’s death.’”

Like Turner, though, Pittman believes that, as a physician, she should respect a patient’s wishes. “I don’t think my job is to change people’s minds,” she said. “It’s to make sure that when they make a decision, it’s an informed decision.”

Turner is hoping that the decision will be informed by patients’ confidence in their own doctors.

“So I tell them: ‘The same way I’ve trusted certain people my entire life, I ask you to trust me. Trust the person you come to when your child falls and breaks their arm. Trust the same people who deliver the baby when your wife is pregnant. Trust UMMC, which has given so much and has made sure anyone in Mississippi who wants a COVID test gets it.’

“And most of those patients have said, ‘You got me, Doc. Where do I sign up?’”

Still, even though Turner has been vaccinated and his patients know it, about 5 percent of them say they never will be. “But I think they will come around, in time,” he said, “after they see that an eggplant isn’t growing out of the side of my head.”