Articles

Hearing Loss and its Effect on Brain Function

By Grace Sturdivant, AuD

By Grace Sturdivant, AuDPatients most commonly come to me with gradually-acquired sloping hearing loss. What does that mean? Well, most commonly, individuals are able to hear low pitch or bass tones better than they are able to hear high-pitch or treble tones. Functionally, this results in the common complaint of “I can hear but I can't always make out what people are saying.” Or another common statement, “I can hear fine one on one, but when I get into groups or crowds where there is background noise, I have trouble understanding people.” Some patients are resistant to trying hearing technology for a variety of reasons ranging from an outdated negative stigma associated with older hearing aids, to an intimidation of learning how to properly use and take care of new technology.

My job as an audiologist is to make the process simple - to explain the hearing loss diagnosis clearly and to lay out appropriate options for technology. With my adult patients, I consider it part of my job to convey the impact of hearing loss and the advantages of using hearing technology - both for the more obvious quality of life improvement and for the less known physiological cognitive component. Hearing loss truly affects the way our brains operate, and this can be a more compelling reason to make the jump to embrace hearing technology than a more simple annoyance.

There are two primary neurobiological changes that I typically discuss with patients. One is called Cross-modal Plasticity. Don't let that term bog you down - it means that when the area of your brain which is purposed for processing sound (the auditory cortex) is not being stimulated adequately (i.e., when hearing loss is present), a well-functioning system like vision will begin to recruit that area to process its own input. To illustrate this, studies have shown that even in mild sloping hearing losses like the one I described earlier, when visual stimuli are presented to patients, unexpected activity is recorded in the auditory cortex. So the auditory cortex is working to process the visual stimulus. This finding has been correlated with increased difficulty with understanding speech in noisy environments. So the difficulty you are experiencing in noise is not just because you've lost the ability to perceive some of those higher pitches, but also that your brain is re-organizing because of the lack of sound stimulation.

Another fancy term to describe the second brain change I'll discuss is Cortical Resource Reallocation. Even in these mild, sloping hearing loss cases, auditory cortex activity is decreased and frontal lobe activity is increased on listening tasks. Why does this matter? Well, the frontal and pre-frontal areas are critical for working memory and executive function. When hearing loss is present and you are straining to hearing and understand someone in a challenging environment, your frontal lobe is loaded down with trying to understand what someone is saying in that moment. We call this “effortful listening.” This leaves less ability for that frontal lobe to help you remember what someone was saying after you walk away from the conversation.

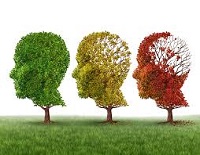

People have often not considered that hearing loss means that the brain is less stimulated. We do truly hearing with our brains! It could be due to these reasons that people with severe, untreated hearing loss are five times more likely to develop dementia; or that adults with untreated hearing loss develop cognitive decline 3.2 years sooner that people with normal hearing; or that people with dementia and severe untreated hearing loss have rates of cognitive decline 30-40% faster than dementia patients with normal hearing. I don't intend these facts to be scare tactics, but they are evidence-based and are relevant to the conversation. We can all agree that brain stimulation is important from infancy until the end of life.

I'd like to emphasize that we have not proven that hearing aids can prevent, delay, or slow cognitive decline. But we have proven that hearing aids allow for cognitively-engaging behaviors which are known to prevent, delay, and slow cognitive decline. Aside from mitigating the brain changes I discussed, hearing aids facilitate social engagement, interaction, and interpersonal connection. They reduce the depressive symptoms of hearing loss. This improves the quality of life and relationships for both the patient and their friends and loved ones. By decreasing effortful listening, patients are less exhausted after socializing, allowing more energy for further engagement with family and friends.

The bottom line is this, if you are struggling to understand conversations - even if the struggle is only in crowds - go to see an Audiologist. Find out where you stand and be open to exploring the technology available. Hearing aids can be as simple or hands on/techy as you want them to be. Most styles are nearly invisible! They can be fully automatic so that you never have to manipulate them, or they can be synced with apps on your phone for unprecedented controls and wireless streaming. At UMMC, we offer returns and exchanges for the first 60-days aside from the smaller, non-refundable professional services fee. This allows you to try hearing technology at minimal risk. Hearing aids are an adjustment, but the positive outcomes we see with our patients makes the Audiology profession a truly rewarding one.

- Campbell J, Sharma A. (2014) Cross-modal re-organization in adults with early stage hearing loss. PLos ONE 9, e90594.

- Campbell J, Sharma A. (2013) Compensatory changes in cortical resource allocation in adults with hearing loss. Front Syst Neurosci 7.

- Deal JA, Sharrett AR, Albert MS, Coresh J, Mosley TH, Knopman D, Wruck LM, Lin FR. (2015) Hearing impairment and cognitive decline: a pilot study conducted within the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. Am J Epidemiol 181(9): 680.690.

- Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, Xue Q-L, Harris TB, Purchase-Helzner E, Satterfield S, Ayonayon HN, Ferucci L, Simonsick E. (2013) Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 173(4): 293-299.

- Lin FR, Metter EJ, O'Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zondervan AB, Ferucci L. (2011) Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 68, 214-220.