Join the resistance: Help defeat superbugs

Published on March 31, 2017

The World Health Organization has signaled for help in defeating a group of notorious villains.

They are the “superbugs” - bacteria with the ability to overcome our best defenses. The WHO published a list Feb. 27 prioritizing 12 bacterial strains in need of new antibiotics. The list encourages research and development into such drugs - the new superheroes.

The world needs these treatments: In the United States, antibiotic-resistant bacteria infect two million people and kill 23,000 each year, primarily those who are hospitalized or have weakened immunity. But these species are usually harmless, living among and within us.

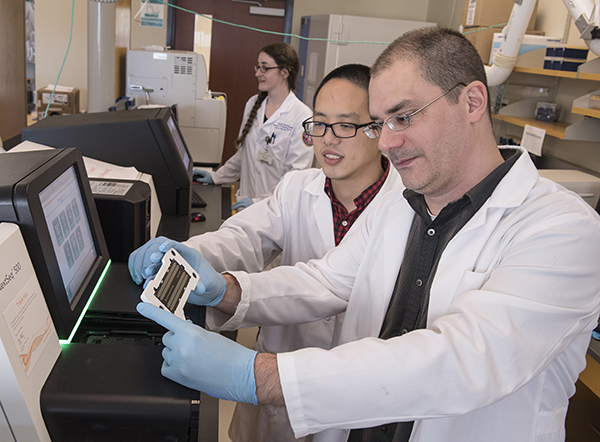

Dr. Ashley Robinson, foreground, and Xiao Luo prepare to load a DNA chip on a sequencing machine in UMMC's genomics facility.

Dr. Ashley Robinson, UMMC professor of microbiology and immunology, studies methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, one of the WHO's “high”-priority pathogens. One in five people carry benign S. aureus strains in the nose, while three percent of people have an MRSA.

“What causes the switch from susceptible to resistant is a huge area of research,” Robinson said.

Robinson studies MRSA genomics. By taking millions of DNA fragments and putting them in sequence, his lab looks for the genetic switches. His work has helped draw a “family portrait” of S. aureus in North America, including the MRSA strain.

“Genomics are a window into studying the transition,” Robinson said. However, that window is more like a moving target. “The common drug-resistant strains now are not the same ones that were common earlier.”

When bacteria survive antibiotic treatment, they can pass on the trait that helped them survive to their offspring. These bacteria also can survive the antibiotic attack. Because bacteria can double their population size in 30 minutes, the trait can proliferate quickly.

“The more we use a particular antibiotic, the less useful it becomes,” said Dr. Brian Akerley, UMMC associate professor of microbiology and immunology.

By age 3, 75 percent of children get an ear infection, the top reason they are prescribed antibiotics. Akerley's study species, Haemophilus influenzae, is a common cause.

Akerley also uses genomic techniques to study bacteria - determining which genes can make H. influenzae antibiotic-resistant. Recently, he and his colleagues have studied ways to target the bacteria using immunotherapeutics, which would bind to the bacteria and inhibit its ability to cause illness.

“The idea is to teach the pathogen to be less pathogenic,” Akerley said.

H. influenzae is a WHO “medium” priority because current treatments still work well. However, scientists have been tracking its increasing resistance to ampicillin since the 1970s.

Marquart

“With every new drug, [bacteria] can figure out a way to overcome it,” said Dr. Mary Marquart, UMMC associate professor of microbiology and immunology.

Marquart studies Streptococcus pneumoniae, another WHO “medium” priority. While the extent of resistance in the species isn't “alarming” yet, she said the potential is there.

Bacteria can acquire resistance and virulence through gene transfer, she said. Cells of different species can trade DNA fragments like baseball cards. A benign denizen of your lung can become a superbug after receiving a new gene from an antibiotic-resistant neighbor.

Between antibiotic misuse and the natural abilities of bacteria, Marquart said microbiologists think we are approaching a “post-antibiotic era” - when the most resistant strains won't submit to any antibiotic. For some species, that era might be closer than scientists think.

McDaniel

Since its discovery in the 1960s, Acinetobacter baumannii has become a “scary one,” said Dr. Larry McDaniel, UMMC professor and interim chair of microbiology and immunology. “When it first described in the Vietnam War era, it was pan-susceptible to antibiotics.

“In less than 50 years, not only has it developed multi-drug resistance, but also virulence.”

The species is a “critical” priority pathogen, the WHO list's top ranking. A study by McDaniel and others showed A. baumannii strains can survive in blood, suggesting their ability to cause serious infections like sepsis.

O'Callaghan

Another “critical” priority is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Or as Dr. Richard O'Callaghan calls it, “Genghis Khan,” a merciless conqueror.

“The resistant strains are known to infect people with conditions like cancer, cystic fibrosis and severe burns,” said O'Callaghan, UMMC professor of microbiology and immunology. “These are people who don't need any more problems.”

The WHO's recent list aligns with O'Callaghan's own top 10 “bad bugs” presentation he has used in microbiology classes for years, including most of the species named in this story. O'Callaghan's previous work aided in the creation of two antibiotics used for P. aeruginosa eye infections. He said although new antibiotics are in the drug development pipeline for various species, it's been “decades” since the FDA has approved a new class.

But while the WHO stresses the importance of new antibiotics, UMMC researchers say this is only part of the solution.

For example, Robinson cited a 2017 study that attributed a 30-percent decline in MRSA infections to better screening, hand washing and infection-prevention emphasis at hospitals.

McDaniel said health care providers should also practice antimicrobial stewardship - “knowing when and how often to prescribe an antibiotic and when to switch drugs if needed.” UMMC's own stewardship program helps providers make the optimal choices for their patients.

Everyone can take steps to prevent superbugs. The WHO recommends people follow their health care provider's instructions on antibiotic use and limit exposure to potential sources of infection. By following these steps, we can all be heroes in the resistance against superbugs.