The son will see you now: Holdiness’ path winds back to father’s practice

Published on February 22, 2016

In Kosciusko there was a doctor whose patients came to him, not only because he could make them better, but also because he could make them laugh.

Then, on a Sunday afternoon in May, the kind of day he lived for, soaking up the countryside on his bike, he was gone - just eight years after a traffic accident had taken one of his sons.

There was no one else like Dr. Gary Holdiness. No one could replace him, or try. Then, in the summer of 2015, a new doctor came to town. His name is Holdiness, too.

TEARS

Kosciusko - This is his dad's examination room. Much of Dr. Gary Holdiness' medical equipment and furnishings are still here.

“I didn't re-decorate,” says the new doctor. “I don't know why.

When Dr. Samuel “Sam” Holdiness walks into this room to see his patients, he says, some of them start crying. “l tell them, 'No more of that. This is not a sad time.'”

More than 7,200 people live in Kosciusko, but when just one of them died nearly 4 years ago it was as if half the town was gone. At least, the patients of Gary Holdiness must have felt that way.

Now, his older son, who never wanted to be anything but a doctor, has come back home, hoping his dad's patients will come back, too, hoping to make his father's practice his own.

What does it take to do that, to win over a group of people who tell you a dozen times a day, “'I loved him, I loved your father'”?

Who was Sam Holdiness' dad?

Dr. Gary Holdiness

“A goofball,” he says, with a mix of admiration and bemusement in his voice. “He rode his bike to the clinic, and then he rode it in the clinic.”

He pulls out a photo of his father, whose hair is done up in cornrows. “He let a patient, or maybe it was a nurse's aide, do that.” This was a doctor whose stethoscope sometimes rested against his overalls.

Even Donna Holdiness, who was married to Gary Holdiness for 30 years, says her husband was “different.”

“They finally had to tell him he couldn't make his rounds wearing rollerblades,” she says. “That's just who he was; he liked to be healthy and active.”

A triathlete - competing as a swimmer, runner and biker - he enjoyed cycling most of all, a love affair that bloomed when he was a kid growing up in Louisville, where he delivered medicine for a pharmacist on two wheels.

“Biking was his freedom,” Donna Holdiness says. “As an adult, he rode to release stress and to work out his body in a healthy way. It was also something he could do as he aged.”

He was a young medical student when he first met Donna at First Baptist Church in Jackson when she was working at a McRae's department store. They were friends for two or three years before he asked her out. They married in 1982, and about three years later, in Selma, Alabama, where Gary started his residency in family medicine before finishing it in California, they had their first child.

“Samuel's very much like his father,” Donna Holdiness says. “He's a people pleaser. He always thinks of everyone else before himself.

“From first grade on he knew he was going to be a doctor. We didn't even have to talk about it. It was his goal and he never got off that path, not once.

“When he started first grade he knew he had 12 to go. On high school graduation night, he came home and said, 'Now I'm back to first grade.' He knew he had another 12 to go.”

Their second son, Matthew, was born 22 months after Samuel - the name Donna Holdiness still calls her older son. The brothers grew up fighting, of course, but became closer, ironically, after Sam left home for college.

“Matthew had tons of friends, and was full of life and full of energy, blowing and going, but didn't really have a clue about what he was going to do,” Donna Holdiness says. “One day, it was a plastic surgeon, one day a lawyer, one day a kickboxer. Whatever it was, he knew he was going to be great at it.”

Sam and Matthew inherited their father's compassion. “Gary would go hiking on the Natchez Trace and take a Bible with him to read; sometimes he came back empty-handed,” Donna Holdiness recalls. He had given his Bible to some lost soul he saw wandering on the road.

“It was the same story with his shoes,” Donna Holdiness says. “Sometimes he'd come back home without his shoes.”

There were similar stories about Matthew, but his mom didn't hear some of them until his funeral. “He would give away his coat to a kid in school who didn't have one,” she says. “He'd tell us he had lost it.”

People in Kosciusko will remember Matthew Holdiness' name for many reasons. The family made doubly sure of that with the establishment of the $1,000 Matthew Holdiness Scholarship, awarded to a high school senior on Kosciusko High School's baseball team.

Matthew had been a baseball standout before his death at 18 in August 2004. The aftermath of the fatal car crash was more than most families have to endure. How do you survive the pain once, much less twice?

“My strength is my faith and security in God Almighty,” Donna Holdiness says. Essentially, these are the words she also says to high school students, church congregations and other groups who wonder how she gets through each day.

“On days I feel sorry for myself and cry, 'Why me?' he wraps his arms around me and says, 'Because I have a perfect plan for you; trust me.' And I do.

“I try not to question it anymore. I'm only flesh and blood, so no earthly words would help me understand why my son is gone. No answer to a mom or wife would be good enough.

“This is what I tell people. Some get it, and some don't.”

HOPES

Dr. Sam Holdiness, left, consults with Kimberly Cuny, R.N. Holdiness’ father, Dr. Gary Holdiness, wrote her a recommendation for her entrance into nursing school.

Kimberly Cuny, RN, arrived for work at the Kosciusko Family Clinic about two weeks before Dr. Sam Holdiness.

“His dad was the physician for my mom, dad, husband and even my grandparents when they were still living,” she says. “He was my doctor for years. He treated patients like they were part of his family. He was a great physician and a great man.”

Gary Holdiness wrote her a recommendation for her application to nursing school, Cuny says. “He told me, 'I have no doubt you'll finish.' But he didn't get to see me finish.”

Sam Holdiness doesn't talk much about the emptiness his father's death left behind; he prefers to talk about the fullness of his life when he was here.

While earning his M.D. at the Medical Center, Sam did his fourth-year rotation at the Kosciusko Medical Clinic. His mentor was the man who wrote Cuny's recommendation.

“That was a blast,” he says.

It wasn't the first time he and his dad had been to work together: As a kid, Sam accompanied him on emergency calls. “I stayed in the doctor's lounge,” he says. During junior high and high school, when he wasn't swimming or playing tennis, he would hang around the clinic. One summer, he worked as a nurse's aide.

All of that was early training for his destiny, a fate sealed even tighter, it seems, during his high school years.

His Advanced Placement biology teacher, Sylvia Blaylock, “made the course fun, and she had high expectations,” he says. As far as he can remember, her senior AP class yielded a couple of PTs and OTs, and three M.D.s.

Sam Holdiness graduated with his degree in May 2011, one year, to the month, before the accident on the parkway. Gary Holdiness, 54, was struck by an SUV at 78 mph, news reports said. Apparently, the driver had been texting.

The collision erased 25 years of medical experience, the life of the party and Donna Holdiness' “best friend.” It could have left in its wake much bitterness. Instead, one bequest is the Gary Holdiness Cycling Fund, created by his family and friends.

Overseen by the Natchez Trace Parkway Association, donations to the fund pay for safety and awareness programs, cautionary signs, orange riding vests, bike lights and more on the road where Gary Holdiness spent much of his life.

Whenever grief takes hold, Donna Holdiness has the words of her late husband to fall back on. He would count himself blessed, he would say, “'if the Lord will be so good as to call me home while I'm doing something I love.'

One day after the accident, on May 7, 2012, the Jackson Presbyterian Examiner ran a tribute by Daniel Townsend, who grew up in Kosciusko

“It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that Dr. Holdiness saved my life,” Townsend wrote.

When Townsend remembers Gary Holdiness today, he sometimes thinks of grits, candy bars, milkshakes, and redemption.

He recalls how, at age 11, within the span of a few months he had lost half of himself. “I went from about 140 to 70 pounds,” he says. “I was depressed. I had stopped eating.

“My parents tried, but weren't able to help me; finally, they took me to our family doctor.”

Now in his 30s and living in Brandon, Townsend recently found Gary Holdiness' 20-year-old “prescription” for him stored in the back of a closet. It was a weight gain chart, a calorie plan that included some dishes Townsend had never eaten before. “I was always a picky eater. I had never had Zero candy bars,” he says, “or grits.

“But the idea of keeping a chart and journals, this quest to regain weight, became fun.” Most of all, he says, his doctor never judged him. “He didn't come across as angry at me, even though I was being stupid by not taking care of myself.

“Just knowing he cared was a big boost.” Within three months, he says, he had gained at least 45 pounds.

“When Dr. Holdiness passed away, it left a pretty big void in the town. It will mean a lot to a lot of people to have Samuel there.”

COMMITMENT

In one of his father’s old examining rooms, Dr. Sam Holdiness takes his time with patient Rickie Parks.

This is his father's office. At the time of this interview, Sam Holdiness' framed degrees are still sitting on the floor waiting to be hung. But on the wall there is the mounted head of a buck he shot.

“My wife said, 'That won't be in my new house,'” he says.

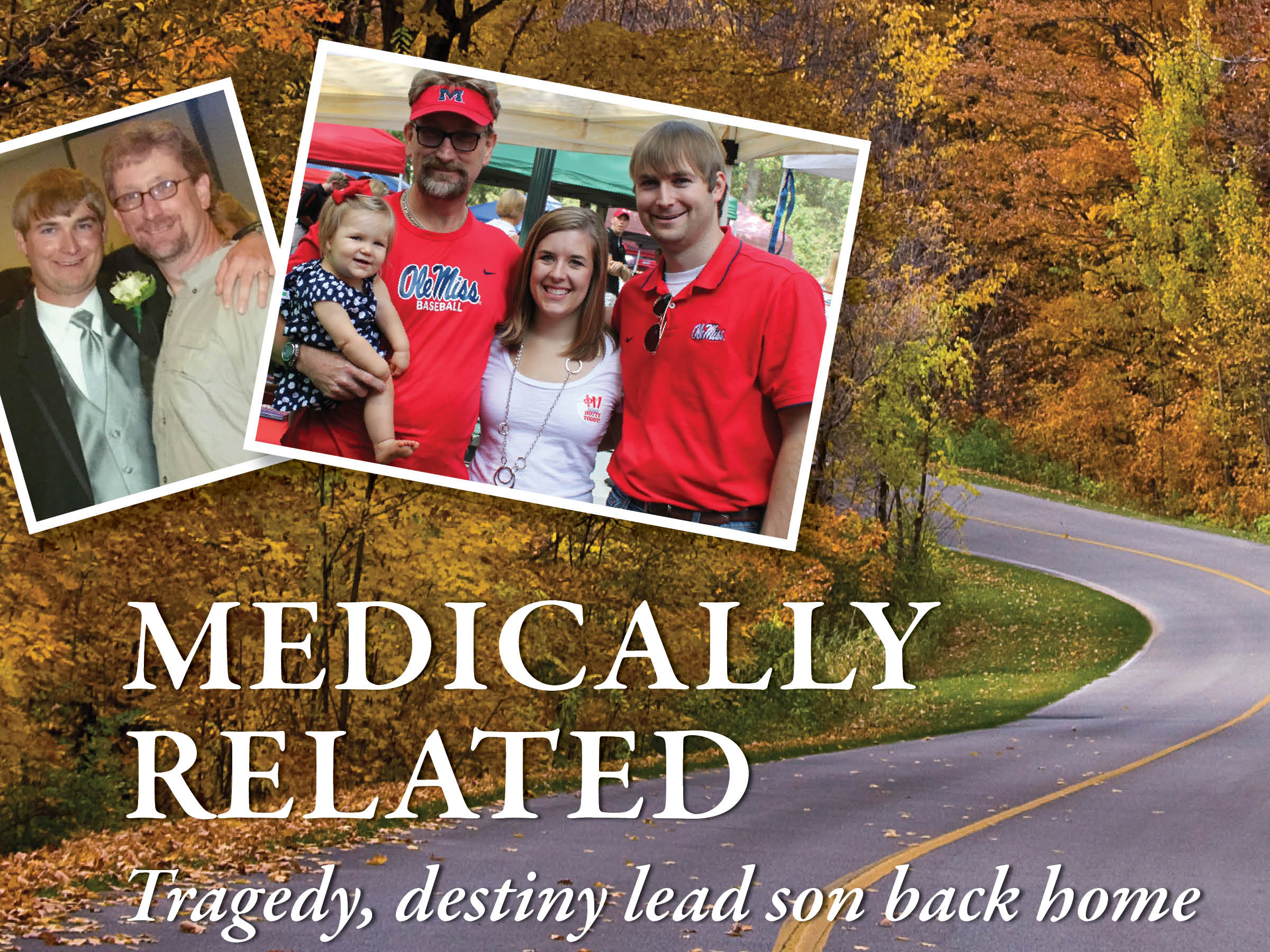

He and Amber, a pharmacist, met at Ole Miss. Like his father, Sam Holdiness is a huge Rebels fan. Also on the wall hangs an Ole Miss-themed painting by artist Ian Greathead of a sailboat on the water and a pint of Guinness. It was a gift from his parents when he graduated from medical school.

About a year later, he was in his residency when his father died.

It was at the University of South Carolina, where Sam was learning a specialty he had never heard of before he was a medical student. “There was a resident at the Medical Center, Natalie Baker, who talked me into internal medicine/pediatrics,” he says.

“I knew I wanted to do something with adults, but I also knew I have the personality to work with kids. Natalie said, 'You don't have to pick. You can do both.'”

She introduced him to Dr. Jimmy Stewart, an IM/Peds specialist at UMMC, he says, “and Dr. Stewart finished the sale.”

Sam Holdiness earned his M.D. as a Mississippi Rural Physicians Scholar; he's committed to practicing in Kosciusko for three years.

“But we bought a house here,” he says. “We're not going anywhere. The past few years it's been, 'what's next?' Now there's no more 'what's next' and that makes me happy. The only 'what's next' is 'when's the next Ole Miss football game?'”

Sam and Amber came to Kosciusko with their three children: daughter Morgan, 5, and their two sons. The older one, age 3, is named Matthew. The younger one, Luke, was born in February; his full name is Lucas Gary.

Sam's father, always eager to indulge his bike-riding passion, had decided to practice in Kosciusko partly because of its proximity to the Trace Parkway. Although Sam Holdiness enjoys bike riding as well, he is also a fan of sailing, the opportunities for which are sorely lacking in landlocked Kosciusko.

So he returned for different reasons. During his second year in medical school he remembered a vacation in San Francisco, a place with “too many people.” All he knows is small-town living. The choice of towns was obvious.

And of course, there was his father' death. The death of the irreplaceable doctor.

LAUGHTER

Sally Gladney, right, has a surprise revelation for her new physician.

After a few weeks at the clinic, Cuny could see Gary Holdiness in his older son: “He has a lot of mannerisms like his dad's,” says Cuny, the RN.

“He's a good physician like his dad; he laughs like his dad.”

It's a late September day at the Kosciusko Medical Clinic, a month or so after Sam Holdiness' arrival, and the official tally is threatening to reach the 30-patient mark. Already, a 20-patient day is a “slow” one.

One of those patients is Sally Gladney. Gary Holdiness took care of her for as long as he was in practice.

When Sam Holdiness greets her, in his dad's old exam room, her response is earnest, if predictable: “I loved your father,” she says.

“Dr. Holdiness was on call when my mother was dying and her doctor was off. I told him, 'My mother's dying, can you help me?'

“He called Baptist Hospital; they told me to bring her on in ... and that's when they found out she had lung cancer. He saved her. We had six more months with her that we wouldn't have had. I thank your father for that.”

This is the shade, the long shadow that Sam Holdiness must work under. Or is it?

As her new doctor asks her about her blood pressure, about her “sugars,” as he goes over her chart with her, point by point, spending time with her when he has about two dozen more to see this day, Gladney is fidgeting, as if there's something she can't wait to tell him.

Finally, she says, “Look, I'm getting married.” And she holds out her hand to show him the ring. As if he's part of the family. As his father was.